Lisa Kenoras, a Secwepemc woman, sits by the Shuswap river in her home community of Splatsin First Nation, where she began her work as an MMIWG advocate. Photo submitted by Lisa Kenoras

Lisa Kenoras was at a rally where youth were occupying B.C. legislature steps in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en on what is shared territories known as Victoria, B.C., when a man slipped a note in her hand that shook her to her core.

Kenoras, who is a Secwepemc woman living in W̱SÁNEĆ territories and a student at the University of Victoria, didn’t know the man or expect to be handed the note at the rally on Feb. 24.

“I was stunned,” Kenoras tells IndigiNews over the phone.

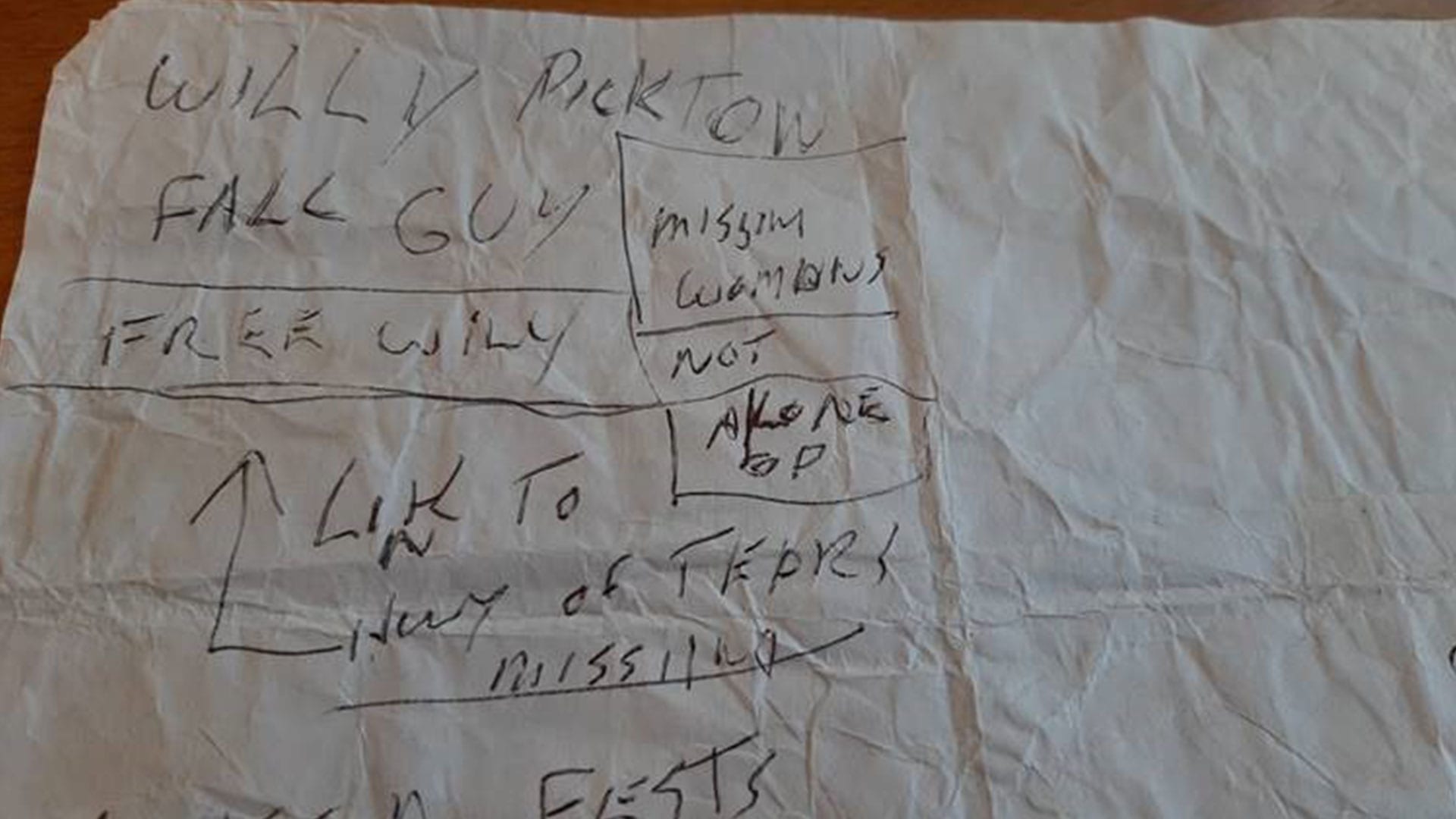

The Note

The man had left Kenoras two pieces of paper, a note and a drawing.

“I turned to my right and then I looked in my hand, and I’m like, ‘what is this?’” Kenoras says.

“It’s kind of like a crumpled up piece of paper. And then I open it. And the first thing I see in big letters was ‘FrEE Willy.’”

The note also has another message that says, “Link to Hwy of tears missing.”

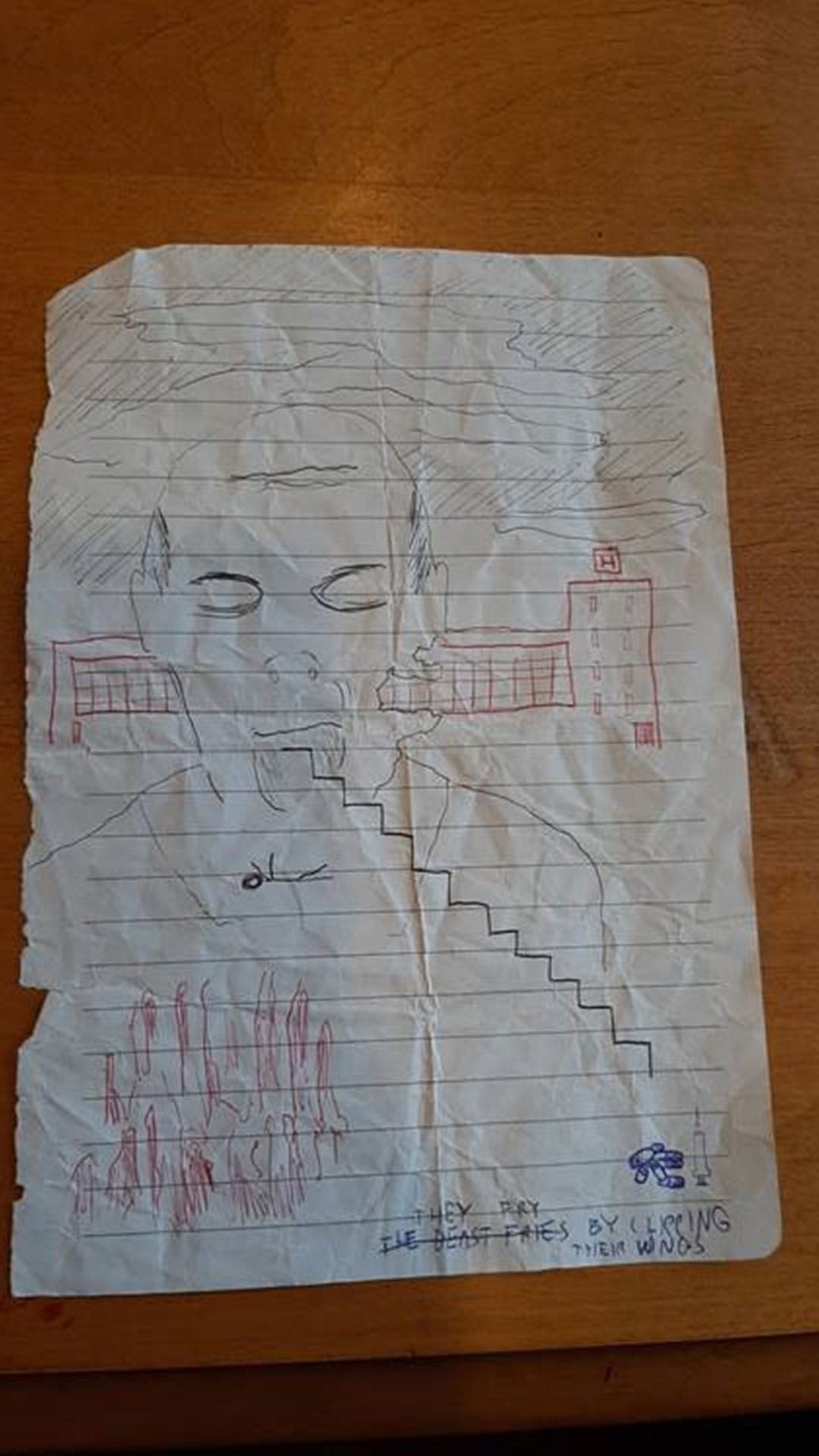

The second piece of paper is a drawing of a person, presumably Robert “Willy” Pickton — who was convicted of second-degree murder in the killing of six women in 2007 — with stairs coming out of his mouth.

At the bottom of those stairs is drawing of a needle and pills with the words: “They fry by clipping their wings.”

Below that is another message that’s been crossed out: “The beast fries.”

Kenoras has been an advocate for MMIWG in several territories across so-called B.C. She says after she received the note, she experienced Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and after honouring her healing journey, she says she decided she wouldn’t be a victim of violence any longer.

Kenoras lives away from home to attend school and is working towards a degree in Indigenous studies with a minor in political science. So for her, the fear of living away from her community and support system is very real, she says.

After receiving the note, Kenoras says she felt “helpless” and “kind of shrunk.”

She then began to mentally, emotionally, and physically withdraw from everything and felt it best for her to return to her home community of Splatsin in Enderby, B.C.

“I got really bad PTSD. I was scared to leave my mom,” says Kenoras.

Her mother came to be with her the very same day it all happened, alongside her mentor and “activist aunty.”

When she returned home for three months after the pandemic began, she started asking questions that eventually led her to develop the Matriarch Resistance, a safety group for Indigenous women.

The Matriarch Resistance is Born

“I was thinking, I was crying, and praying. I was like, what can I do? What can I do? I started to feel helpless,” Kenoras remembers.

She thought of the abuse and the violence, she says, but also her perseverance.

“[I’m] still going to school, still on sobriety — walking this path,” she reminded herself.

“There’re many other women that face the same thing, but they have nowhere to express it. There’s nowhere to talk about it.”

She decided she would not back down or back away from the important work that needs to continue, she says, so she spent the past year studying Muay Thai and building a kinship circle of powerful Matriarchs.

The group became the Matriarch Resistance and was meant to provide a space for women to have a safe group to turn to when they are living away from home, or just need an outlet to express themselves using physical activity and self-defense.

“Matriarch Resistance is a fitness program designed for Indigenous women, through the practice of boxing and kickboxing techniques and skills,” says the group’s private Facebook page.

“The program will be created for all levels of fitness while gaining self-confidence and self-awareness,” the page says. “The inspiration for Matriarch Resistance is to keep our Indigenous women safe.”

Kenoras says that she finds it difficult to be a “young Indigenous woman” who is a student all while “reclaiming culture [and] self-identity.”

“[It’s]constant political violence against Indigenous women,” says Kenoras.

She wanted to transform her pain into strength, she says, and work with other women to empower themselves.

Matriarch Resistance is meant to offer space for training, but also for sharing and engaging in a safe place — in response to the “whole oppression of colonization, where they silenced strong Indigenous women with violence and intimidation,” says Kenoras.

Kenoras mentions the killing of Chantel Moore, a Tla-o-qui-aht woman who was killed by police during a so-called wellness check in Edmunston, New Brunswick in June 2020.

Moore was living away from her home community. Kenoras says the women of Matriarch Resistance are working on conducting their own wellness checks.

Kenoras hopes to bring the program to small communities, “keeping our women safe there as well, and our young girls,” she says.

Looking back on the “Free Willy” note, Kenoras says it inspired her to create this program.

“Not just looking at the national crisis, but doing something about it and making it known and calling out the violence,” says Kenoras.

And she says she’d like to leave a message to all women.

“Understanding that embodied fear and loneliness is something that is politically structured against Indigenous women. It’s time for women to pick up our medicine,” she says.

“Overcoming fear is being able to own your power and speak your truth. Being lonely is a part of an opportunity to fall in love with yourself and grow with your spirit, until you are comfortable with being alone and happy.”

“Being alone is the strongest form of self-love. Being in silence, prayers are answered,” Kenoras says.

To follow the work of the Matriarch Resistence or to support the initiative, check out their Facebook page.