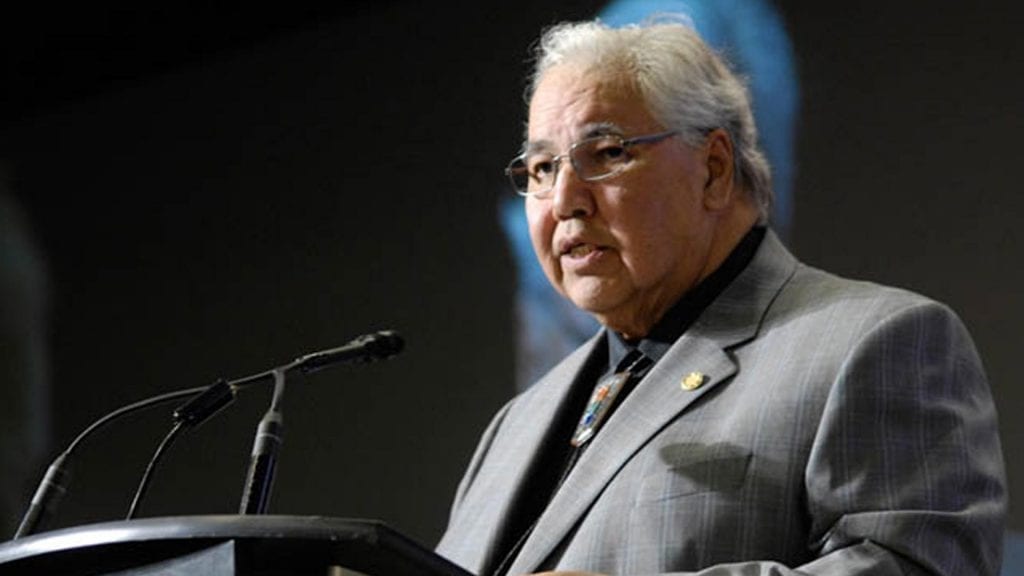

Murray Sinclair delivers the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015. Photo: APTN

As he prepares to leave the Senate at the end of January, Murray Sinclair warns that white supremacists and residential school deniers will likely present major obstacles to achieving reconciliation and decolonization in Canada.

“The people who believe that they have the privilege of holding power and should continue to have that privilege, they’re going to push back,” says Sinclair. “They’re going to fight against reconciliation. They’re the deniers of this story. They’re going to say this never happened. That the schools were all about education and the Indians should be thankful that they got an education.”

He calls out federal Conservative leader Erin O’Toole for encouraging this last line of thinking. Video surfaced last month of O’Toole saying the residential school system “was meant to try and provide education” and then “became horrible” during a conversation with Ryerson University students.

“That message is a total mess,” says Sinclair. “Schools were never about education, schools were always about forced assimilation and indoctrination, and we need to call it for what it is.”

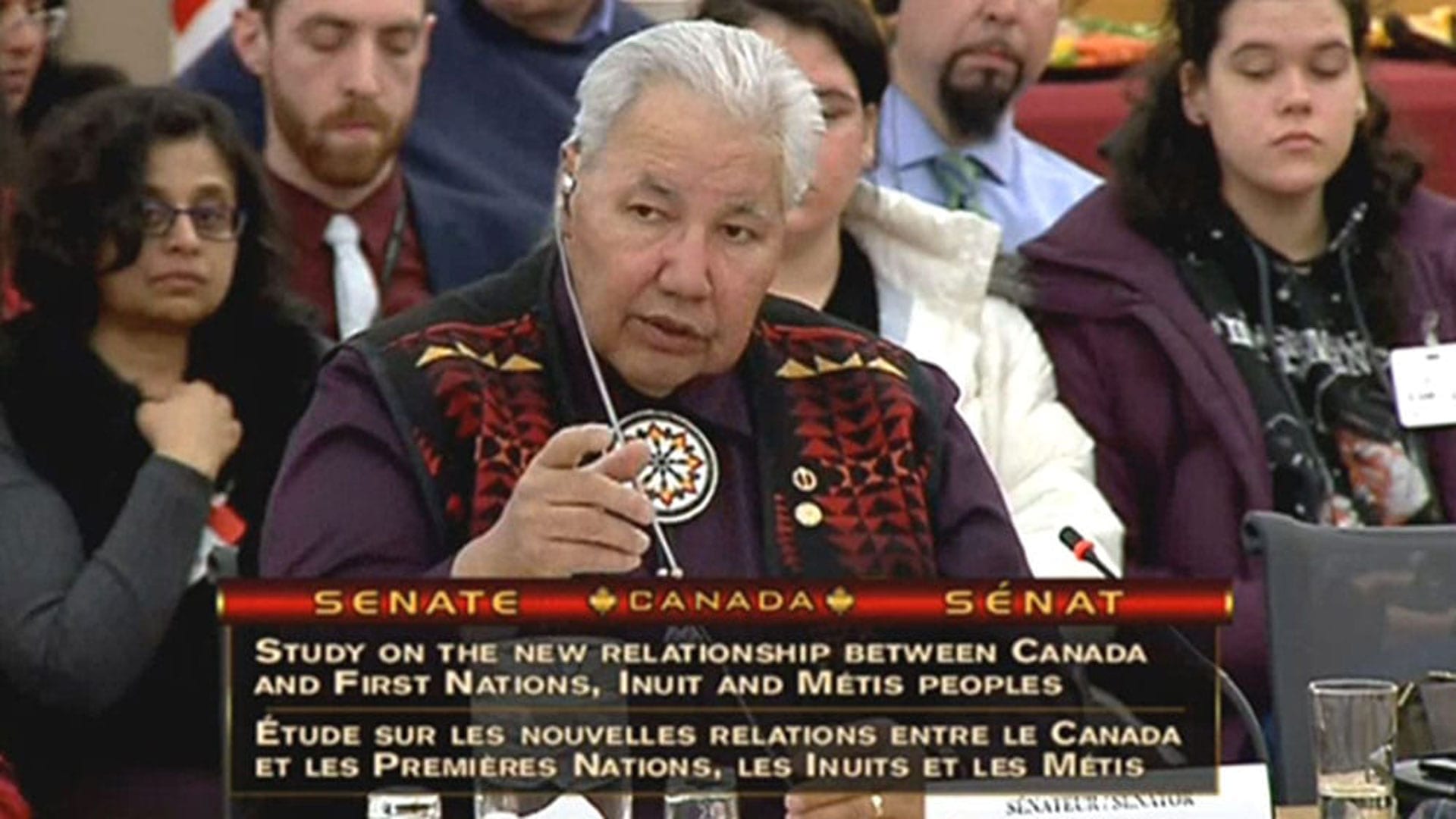

In a sit-down interview with APTN News, Sinclair says there needs to be a fundamental shift in thinking away from ideas that made colonialism possible and still prevent restitution.

Regular Canadians can help root out colonial mythologies of white supremacy by making sure places like schools don’t perpetuate them, he explains.

“Public school systems have largely failed about respect for Indigenous people. They taught everybody that Indigenous people were inferior, had no rights, had no existence, had nothing worth talking about, that they were heathens, savages, pagans, uncivilized, that they were lucky Europeans came here and saved them from extinction – which is all mythology,” he says.

“They basically taught white supremacy, saying that the white Europeans who came here and settled saved this country from being nothing. And therefore, they teach the myth of white superiority. And those twin myths of Indigenous inferiority and white superiority are the terrible results of the public school system.”

Sinclair has become well known for this type of advocacy since become a senator in 2016. He says he learned early on as a young man to balance strong advocacy with respectfulness and a desire to educate rather than cause harm – something he learned from elders.

“When they got up to speak it was always with the thought in mind about, ‘This is something that I think you need to know’.”

Wearing a red sweater and black vest with a small red and yellow fire symbol emblazoned over the heart, Sinclair spends his last Senate sitting day in December seated comfortably in his home office participating by Zoom because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With a storied career behind him as a lawyer, judge and politician, he focusses now on penning his memoirs and mentoring up-and-coming Indigenous lawyers.

He’s not sure yet how and where his book, tentatively titled Who We Are, will begin.

“The one thing that I have learned about myself is that I tell a story well, and so I expect it’ll start with a story,” he says.

Perhaps that story will be set on the former St. Peter’s reserve north of Winnipeg, where, when he was an infant, he lived with his grandparents after his mother died.

“My grandmother, who raised me, had always wanted to be a priest,” he says. “So, throughout my entire childhood until I started high school, my personal ambition and my sense of responsibility to her was to become a priest.”

But he realized in high school that he was ill suited for the clergy. He decided he preferred university but first needed his grandmother to sign off.

“The conversation that we had (about it) was an important turning point in my sense of commitment and responsibility,” he recalls.

“It’s important for people, young people in particular, to learn about their responsibility to their ancestors and holding true to the promises you make to them. And I tell people often in my public recitations that whenever I have important decisions to make she always speaks to me in one way or the other.”

He mentions more than once the importance elders have in shaping good law and governance among Indigenous communities and individuals.

Young lawyers, he says, haven’t always grown up with elders at their side teaching them history, tradition and culture – which he sees as a potential hurdle to the resurgence of Indigenous law.

After graduating from University of Manitoba, a young lawyer himself, Sinclair saw in detail how the justice system stacked the deck against Indigenous people.

Being treated poorly, he decided to leave.

“I didn’t like the way I was being treated in the legal system by police officers, by prosecutors, by other lawyers, by judges who were quite openly disrespectful and probably even racist towards me. And as a result of that I felt that I was not in the right place,” he explains.

“But it was after consulting with an elder that I changed my thinking about what that meant and my responsibility and refocused my energy in a different way.”

Eight years as a lawyer turned into nearly three decades on the bench. Sinclair twice refused a judgeship offer until finally accepting it in 1988. He became the first Indigenous judge in Manitoba and only the second in Canada.

In that same year, he became co-chair of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, a judicial commission sparked by the brutal murder of Helen Betty Osborne, a 19-year-old high school student from Norway House Cree Nation, and the fatal Winnipeg police shooting of J.J. Harper, a community leader and executive director of the Island Lake Tribal Council.

Both cases sparked outcry for a public inquiry into how race factored in Osborne and Harper’s deaths and the lack of justice afforded them. Manitoba asked the commission to examine the nature, extent and impact of systemic discrimination against Indigenous people in the provincial justice system.

Sinclair had another experience that illustrated elders’ central importance when the commission visited Split Lake, a Cree community in northern Manitoba where over half the people were under 30.

“When you have a youth population that large, usually there’s a significant crime rate. There is in most Indigenous communities. But in Split Lake there was virtually no crime,” he says.

They wanted to know why. During the hearings, the commission learned about the monthly feasts the community had for its elders. The free food drew decent crowds who listened as the elders stood and addressed situations facing the community.

The elders spoke up, whether the issue was children running around at night getting into trouble, alcohol coming into the dry community or conflict between spouses.

But they didn’t single wrongdoers out directly. They spoke in a general way that fostered community cohesion and reinforced good values in the youth.

“The role of the elder is very well respected and very significant (there),” he says. “We concluded that’s why the community has such a very low crime rate, very little community chaos and is such a cohesive community.”

Sinclair also led a second inquest after 12 kids died during cardiac surgery in one year at the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre. Delivered in 2000, Sinclair’s report concluded 10 of the deaths were preventable.

Read More:

Murray Sinclair warns of violent rebellion if Indigenous rights continue to be oppressed

Survivors, commissioners come together to talk about reconciliation five years after final report

The next chapter began when he took the reins of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) as chair in 2009.

The TRC was born in 2007 when residential school survivors, churches and Canada struck that largest out-of-court class action settlement in the country’s history.

The commission held hundreds of hearings across the country and eventually delivered thousands of pages and 94 recommendations, or calls to action, in 2015.

He explains that the first 25 calls to action deal with things that must be done immediately: reducing the number of kids in care, creating a better education system, protecting languages, closing the gap in health outcomes and so on.

The next ones deal with reforming the justice system and making it fairer to Indigenous people. Calls to action 43 and up deal with reconciliation and the foundational change that has to happen to reach that goal.

Sinclair says those calls to action remain urgent as ever.

“At the end of the, day reconciliation is about what we can do to make the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people better,” he says, “not just for ourselves but for our children and for our grandchildren because they’re the ones that have to live with the consequences of what we do today.”