Annie Burns-Pieper, Institute for Investigative Journalism and Andrew Russell, Global News

They had unqualified workers on site and required constant supervision, according to one engineer’s blunt assessment.

“They cut corners every day, every day,” said Justin Gee, vice-president of First Nations Engineering Services Ltd.

Gee said he encountered these recurring problems while overseeing the work of a construction firm, Kingdom Construction Limited (KCL), building a water treatment plant 10 years ago in Wasauksing First Nation, along the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, about 250 kilometres north of Toronto.

“You have to be on them every step of the way,” said Gee, who was the contract administrator on the project. “You can’t leave them on their own.”

Today, this plant is among seven First Nations water and wastewater infrastructure projects in two provinces, funded by the federal government, that have all involved work by KCL, an Ontario-based firm.

Indigenous Services Canada has stated that the department has supplied $90 million in funding for the seven projects. The total received by KCL is unknown. Five of the projects have been peppered with a range of allegations including excessive overcharges, deficient work, delays and racism, reveals an investigation by a consortium of journalists from Concordia University’s Institute for Investigative Journalism (IIJ), Global News and APTN News.

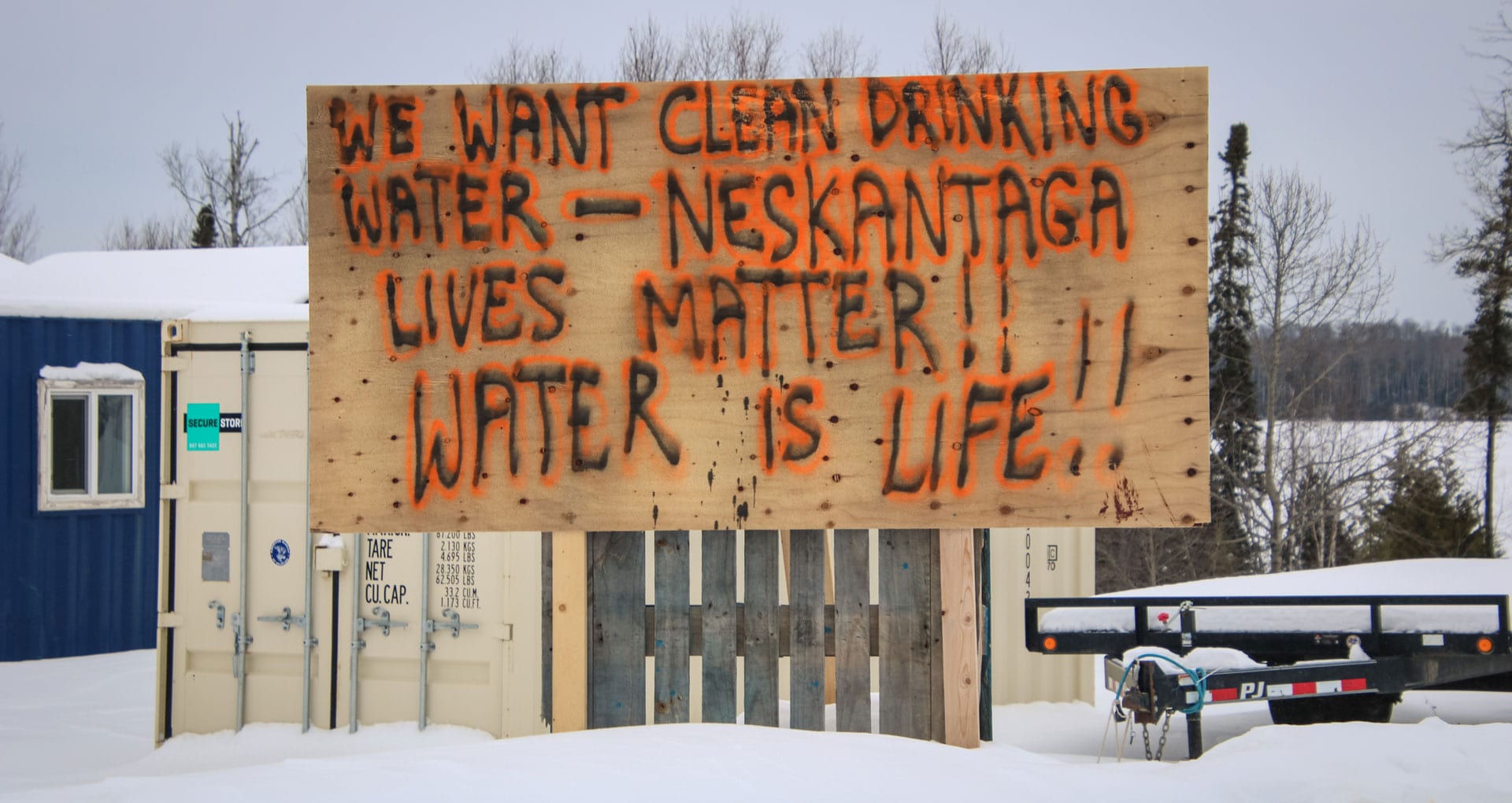

Three of the cases have also triggered legal action, including Neskantaga, a First Nation in northern Ontario on Canada’s longest-running boil water advisory.

In October, more than 250 members of the community were evacuated to Thunder Bay due to a water shut-off after a non-toxic oily sheen was discovered in the water reservoir. This left residents without the ability to bathe or flush the toilet, let alone boil water for cooking or drinking.

“In urban areas, they have problems with water and you see them being addressed right away. Mine has taken 25 years already, going on 26 years. Tell me that’s not systemic racism,” said Neskantaga Chief Chris Moonias.

Community members started returning home in late December.

Over several months, journalists from the consortium reviewed hundreds of pages of court documents and internal records related to KCL, while conducting dozens of interviews with First Nations leaders, members of communities, water operators, and former and current government officials across the country.

‘Shoddy work’

While not referring specifically to KCL, many First Nations told journalists that although cost overruns and delays can affect a variety of infrastructure projects, long-standing federal government procurement policies have forced them to choose the lowest bidders, leaving them with contractors that often aren’t capable of delivering what’s required to ensure clean water on time and on budget.

Despite guidelines that suggest preference be given to companies with a clean performance record, Indigenous Services Canada does not track information about companies that receive contracts for water projects in First Nations communities.

READ MORE:

Trudeau gov. approved $1.9M for contractor that didn’t complete Neskantaga water project on time

Neskantaga members return home just in time for holidays but still on a boil water advisory

The absence of information now poses an obstacle.

Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller said the crisis in Neskantaga is a “particularly acute example” of issues with third-party contractors, and has agreed to calls from Moonias for an independent investigation into the actions of engineers and companies who worked on this project.

“These are investigations that we are willing to support, notably through the initiative of Chief Chris Moonias and Neskantaga, to ensure that where we identify mistakes or sharp practices or shoddy work, that doesn’t reproduce and cascade from community to community,” Miller said in an interview.

KCL was hired in 2017 to construct upgrades to Neskantaga’s water treatment plant. The company was never able to complete the job because Neskantaga asked it to leave the reserve in February 2019 amid ongoing delays on a project that was originally estimated at $8.8 million, but has cost the federal government at least $16.4 million.

The company’s president Gerald Landry said that when his company arrived in the community, it discovered that the situation was “materially different” than what it had expected, based on the contract.

“There were a few large issues that delayed the contract and eventually the owner got upset and terminated the contract,” Landry said.

A general contractor based in Ayr, Ont., KCL has multiple clients that include some major municipalities and has also received contracts to work on water and wastewater systems in Slate Falls Nation, Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation and Pic Mobert First Nation in Ontario as well as Mathias Colomb Cree Nation and Peguis First Nation in Manitoba.

Landry said the company does the work required in its contracts, and he disputes any allegations its work was not adequate.

In November, Landry told APTN News that his company had the best intentions when it started doing contracts in First Nations, but that era was now over: “No more Native work for us. We’ve had enough now.”

“The reason is it’s just too complicated. There’s too much politics, too many players, everybody’s trying to cover their butt,” he said.

“It’s very difficult. You have to play the game and we just don’t want to play any more games.”

In the interview, Landry described federal funding for water infrastructure provided to First Nations communities as “a bunch of free money given to people for nothing, that they never paid for necessarily.”

“When people get given stuff all their life again, and again, and again, and again, I don’t think that’s a good solution to problems,” he said. “We wish Neskantaga and every other Native community nothing but the best in the future.”

In a subsequent emailed statement, Landry apologized for using “culturally insensitive” and “outdated” language.

“I wish to sincerely apologize for using it in a recent media interview,” he said. “We understand many people are still without clean drinking water in our country and this is completely unacceptable. We did our very best to help fix this problem where we could, the solutions to this problem are complex and dependent on many different factors and parties.”

Dawn Martin-Hill, an associate professor of Indigenous studies at McMaster University, said that Landry’s statements from the interview with APTN News are similar to racist comments commonly directed at Indigenous people.

“We deal with that kind of sentiment on a daily basis, whether they think we’re getting free education or free this, like that’s the mantra to justify the deplorable conditions Indigenous people have been forced to live in,” said Martin-Hill.

“Any time we try to get those things resolved, everybody screams money, money, money. And we’re like, do you scream that if it’s white people? Like, do you care how much it cost to get Walkerton fixed?”

In the end, KCL received a settlement of $1.9 million. This was approved by the federal government in October to settle a legal claim KCL launched after Neskantaga removed the company from the project, the consortium reported on Dec. 10.

According to the community’s lawyer, Evan Juurakko of Ericksons LLP, the payment was for “monies owed under the terminated contract and there were no damages paid for breach of contract.”

Landry said the company pursued claims for damages and that claims were settled in a “mutually satisfactory manner.”

“We are the contractor and not the designer or the owner so we can only be responsible for our contract work. The engineers of record are tasked with clarifying the contract in the event there are questions as well as to certify the work performed, which was done and we were paid accordingly, for the appropriate amount completed,” Landry said in a statement.

In 2014 the company was hired by Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg, an Ojibwe First Nation also known as Pic Mobert, located in northwestern Ontario.

At the time, Dave Craig was the water and wastewater manager for the First Nation. One of his roles was to observe construction of the new water treatment plant to assess the completeness of the project. Craig, an engineer, has worked in water and wastewater for 20 years in rural northern communities and First Nations.

He said he was overwhelmed by the construction deficiencies he found.

“It got to me,” he said. “There [were] over 250 at one point.”

Craig said deficiencies, construction issues, spanned from minor to serious safety concerns.

“Things that were in the specification that just weren’t delivered. Tools, lab equipment, and they started cutting corners on things, like, rather than sufficient tools, they’d go down to, like, ToolTown and buy a $4 set of tools. Lab equipment — they substituted all the glass equipment for plastic,” said Craig. However, he could not provide documentation of these issues.

Read More:

Indigenous Services admits feds will miss March 2021 target to lift First Nations water advisories

Craig said most concerning at the time were safety features that had not been installed properly, including gas detectors, which help prevent dangerous situations for plant workers.

“We found they never hooked them up. When we took the cap off the box, the wires were all rolled up in a little ball.”

Orville McWatch was the water plant operator who worked in Pic Mobert after the construction. He, too, worried about the alarms he said had not been installed.

“I thought about it every day,” he said. “If I walk into that room and there’s chemicals, I could obviously get sick or if two chemicals are mixed together, they actually create a gas and it could kill me.”

Norman Jaehrling, CEO for the First Nation, said KCL was similar to the other contractors doing work for the First Nation.

“We typically have issues with most general contractors, and for that matter, with engineers and architects, on all major projects. Kingdom was no exception.”

He said change orders drove the price of the project over the anticipated budget and the community had to go back to the government for additional funding.

Jaehrling said a deficiency encountered on the project, a leak in the distribution system, has never been properly addressed. He said he has documentation of these deficiencies but due to a COVID-19 outbreak in the area cannot find it.

Peguis

In 2018 KCL was hired by Peguis First Nation, about 200 kilometres north of Winnipeg, for the community’s water treatment plant and sewage lagoon upgrades. Work on the $11.9-million project began in April 2018 and was expected to be substantially complete by December 2020.

Chief Glenn Hudson said that in Peguis, the community received work that didn’t meet code, threatened to contaminate drinking water and nearby waterways, and put wastewater operators at risk.

Peguis asked the company to leave.

“The project was two years over schedule. And obviously, they weren’t working with us on a regular basis, on a communicating and decision-making basis,” said Hudson.

Why some First Nations reserves don’t have clean drinking water – Nov 4, 2019

The community is addressing the remaining deficiencies using labour and expertise from the community. He said KCL didn’t seem to be prioritizing work on his First Nation, seemed to be out of its depth, and lacked cultural sensitivity.

“We have people here in our community that can do this work, and they were kind of reluctant to hire them,” said Hudson.

He doesn’t know why, exactly, but suspects community members were overlooked because they are Indigenous, “probably because of the racist approach, systematic racism within their company,” he said.

KCL’s president said it takes all allegations of racism “seriously.”

“We have the utmost respect for the members of the communities in which we have worked and pride ourselves on the efforts we have made to foster good working relationships,” Landry said. “We are not aware of any evidence of racism by Kingdom or its employees – we take any allegation of racism very seriously and have very strict policies and procedures in place to deal with any potential issue.”

Indigenous Services Canada spokesperson Leslie Michelson confirmed that in May 2020, the community terminated its contract with KCL “citing dissatisfaction with the contractor’s performance and lack of use of local resources. Kingdom Construction agreed to terminate the contract and leave the remaining work to be completed by the First Nation’s own construction company, Chief Peguis Industries (CPI).”

Slate Falls Nation

In 2015 KCL was hired to build Slate Falls Nation’s $11.6-million water treatment plant. The federal investment was made to end what would become a 14-year boil water advisory in the northwestern Ontario community.

However, less than six months after the grand opening, the community enacted a new boil water advisory, which lasted 10 and a half months, from August 29, 2018, to July 11, 2019.

Tom Sayers oversees water operations for five First Nations, including Slate Falls, in his role as the overall responsible operator for Windigo First Nations Council. He was also tasked with evaluating the final stages of construction on the new plant.

Like Craig, he found issues.

“There was quite a lengthy list of deficiencies,” said Sayers. “We found that the product that Slate Falls was going to get didn’t have the ability or things in place that would meet the Ontario regulation.”

He said it was clear from the contract documents that the company’s work was obliged to meet this standard.

He said both he and the Ontario Ministry of Environment’s Indigenous Drinking Water Projects Office did inspections, which concluded the plant was not meeting Ontario standards. The report from the province stated that in 2015, it issued a letter that indicated that the plant had the potential to meet provincial requirements “if constructed, operated and maintained according to the design provided by the project consultant.” While the 2018 report concluded the plant was not meeting Ontario standards, it did not assign blame.

Sayers said one of the primary issues he found was with the UV system used to disinfect the water: “If that primary disinfection isn’t working properly, or it’s not tracked, there’s a risk to the community of a waterborne illness.”

While KCL said on its website that it meets with “the ruling elders and or council to discuss how we can mutually work together and partner to achieve common goals,” Chief Lorraine Crane of Slate Falls said the relationship was difficult for her and other community leaders.

She described it as, “really bad, really ugly.”

In January 2020, KCL sued Slate Falls, claiming it failed to pay the bill for unforeseen expenses that arose on the project. The company’s statement of claim asserted, “Slate Falls has been unjustly enriched by the uncompensated supply of its services and labour.”

In the First Nation’s statement of defence and counterclaim, it stated that the work the company claimed was unpaid was not extra to its contract. The First Nation stated in legal documents that it continues to suffer damages due to the company’s failure to repair deficiencies.

The community alleges in the legal documents that “Kingdom acted in bad faith and performed its obligations under the Contract negligently, carelessly and unskillfully and in breach of the obligations that it owed to Slate Falls.”

“As a result of Kingdom’s failure to rectify outstanding deficiencies, a Boil Water Advisory was put in place on August 29, 2018. It was not lifted until July 11, 2019 after Slate Falls retained a third party to correct deficiencies,” the community alleges.

The community denies any money is owed to KCL and if there is money owed, “it is due to inaccurate drawings and design by the engineering firm Keewatin-Aski Ltd.”

Keewatin-Aski Ltd. did not respond to a request for comment by deadline.

Kerry Black is an assistant professor of civil engineering at the University of Calgary who has worked extensively with Indigenous communities on infrastructure issues. She said complaints about contractors and lawsuits between contractors and engineering firms are common, and “the standard approach for a contractor would be to blame the designer. The designer blames the contractor.”

She also noted that for communities that have been on boil water advisories for years, there is heightened scrutiny that wouldn’t be present in a municipal project.

“We believe, without a doubt, that at any given moment of the day, you can turn on the tap and drink the water. That is a fundamentally different process as soon as you step onto First Nations.”

The Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation

In May, the company finished the majority of the work on a new water treatment plant and distribution system for the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation in southern Ontario.

Kelvin Jamieson was the project manager. He said that while there were several change orders and a five-month delay on the project, he doesn’t believe that anything was out of the ordinary.

“I’m going to say they’re probably no different than the general run of contractors,” said Jamieson.

“I would still give KCL a reference. They have … finished the project for the First Nation that they are happy with. It runs according to the design specs.”

Chief of the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation (MSIFN) Kelly LaRocca was reached for comment but said “Our First Nation entered into a mutual confidentiality and non-disparagement clause as a means of moving the project forward through towards completion. Therefore, I am not at liberty to comment as to any complaints.”

She noted that “the engineers and project manager’s vigilance on the project [have] made it a success for the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation, and we will soon have clean water for our community after much hard work, commitment, and perseverance by our entire MSIFN water project team.”

Wasauksing First Nation

KCL has said on its website that it has “a very meaningful, long-lasting, and committed relationship to the First Nations communities in Ontario and Manitoba.”

Ryan Tabobondung, director of public works for Wasauksing First Nation, where KCL worked in 2010, said the relationship was strained, calling it “adversarial, almost hostile.”

“If I was asked today if I would recommend Kingdom to work on a water treatment plant for any First Nation, my answer would be no,” said Tabobondung.

Tabobondung said issues with KCL arose early in the contract, when the community began receiving numerous requests for changes that would drive up the cost of the project.

“We were hit with a significant amount of extras,” he said, adding he remembers one change request coming in for almost $1-million.

“It seems that there was a lot of emphasis placed on finding inconsistencies in the drawings, or possible errors so that it could be charged back.”

Documents from July 2011 reviewed by Global News show that officials with the federal government would have been aware that “KCL was behind schedule by a number of months.”

Leslie Michelson, spokesperson for Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) said “in the case of Wasauksing’s water treatment plant project, Kingdom Construction was awarded the construction contract and completed construction in June 2012. ISC officials participated on the project team, and were made aware of issues raised regarding the construction phase of the project.”

KCL says work was performed to the “highest quality standards.”

Journalists from the consortium attempted to reach the chief and band office for Mathias Colomb Cree Nation over several months regarding KCL’s work on their wastewater treatment plant, however no one was made available for comment.

Landry did not respond to all of the specific allegations, explaining that he could not comment on concerns that did not relate to the scope of KCL’s work. He also said his company’s work was always performed to the highest standards, and that any other suggestion was “categorically false.”

“We are proud of the work we have done in First Nations communities using our considerable experience with water and wastewater projects across Canada. Our work is conducted with the utmost care according to what has been prescribed in our contracts, which are based on engineers designs, plans and specifications. We never walk away from our obligations.”

Landry added that the company provides a one-year warranty on all construction work and “always [addresses] any lingering issues in accordance with our contractual obligations.”

“Inherently, all construction projects have deficiencies and those are addressed in the scope of our work and certified by the engineer when they are satisfied with the final work. Final project payment certificates, signed by the project engineer, confirm the terms of the contract have been met. In any project, there can be unforeseen expenses and potential delays, but these additional costs are always approved by the design Engineers based on the facts on the ground. Payments are rewarded accordingly, and only when work is completed.”

The consortium asked if Indigenous Services Canada knew of concerns in other communities prior to KCL’s bid for work in Neskantaga. Michelson, a spokesperson for ISC, said officials were made aware of issues raised during the construction phase in Wasauksing but did not comment on whether the department was aware of broader concerns.

“ISC provides funding to First Nations to undertake infrastructure projects that they propose,” Michelson said. “First Nations hire professional project managers to manage the project on their behalf and consultants to complete the design components and administer the construction contract. First Nations are responsible for tendering the construction portion of the project, with assistance from their project manager and consultant, in accordance with all applicable laws, policies and regulations.”

—With additional reporting from Melissa Ridgen, Brittany Hobson, Tom Fennario (APTN News), Laurence Brisson Dubreuil (IIJ, Concordia University), Emma Wilkie (IIJ, University of King’s College), Krista Hessey, Daina Goldfinger and Katherine Ward, Global News.

Below is the full response from Gerald Landry, the president of Kingdom Construction, to questions from our investigation:

Further to my yesterday where I outlined some of the inherent complexity of lump-sum hard bid projects, I wanted to provide you with answers to your questions regarding the work we have done with First Nations communities over the past decade.

Hopefully I address your questions in my response and provide you with more context about how we have performed difficult work in remote communities, in collaboration with First Nations, Engineers, other trades, suppliers and government funders.

I’d like to start by saying that our construction work is always performed to the very highest quality standards. We pride ourselves in doing excellent work and public documentation and project payment certificates can attest to this. Any suggestion otherwise is categorically false.

We are proud of the work we have done in First Nations communities using our considerable experience with water and wastewater projects across Canada. Our work is conducted with the utmost care according to what has been prescribed in our contracts, which are based on Engineers designs, plans and specifications. We never walk away from our obligations. We perform the work as outlined in our contract and as such, cannot comment on concerns being raised when they are not part of our scope of work.

We provide a one year warranty on our construction work and always address any lingering issues in accordance with our contractual obligations. Inherently, all construction projects have deficiencies and those are addressed in the scope of our work and certified by the engineer when they are satisfied with the final work. Final project payment certificates, signed by the project engineer, confirm the terms of the contract have been met. In any project, there can be unforeseen expenses and potential delays, but these additional costs are always approved by the design Engineers based on the facts on the ground. Payments are rewarded accordingly, and only when work is completed.

Even when we had successfully completed our share of the work on these projects we understand the disappointment that is felt when there is dissatisfaction with the outcome or the project as a whole is not ultimately completed.

We have the utmost respect for the members of the communities in which we have worked and pride ourselves on the efforts we have made to Foster good working relationships. We are not aware of any evidence of racism by Kingdom or its employees – we take any allegation of racism very seriously and have very strict policies and procedures in place to deal with any potential issue.

I acknowledge the use of the term Native is culturally insensitive and outdated and I wish to sincerely apologize for using it in a recent media interview.

We understand many people are still without clean drinking water in our country and this is completely unacceptable. Why we did our very best to help fix this problem where we could, the solutions to this problem are complex and dependant on many different factors and parties.

I sincerely hope the above is helpful in understanding the original contractors point of view.

Gerald Landry

PRESIDENT

KINGDOM CONSTRUCTION LIMITED