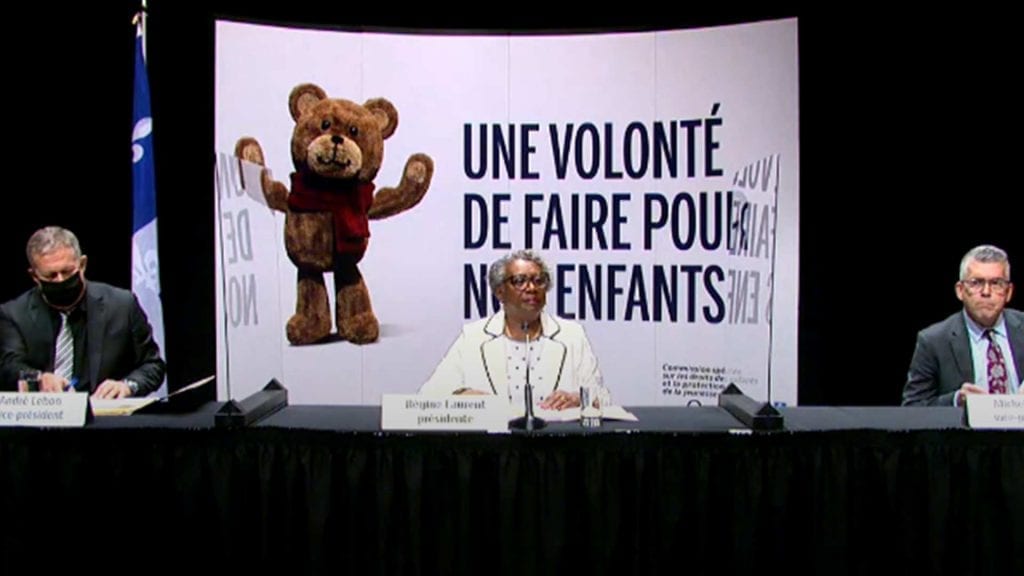

President Régine Laurent holds a news conference Monday.

While tabling the preliminary report for the inquiry known as the Laurent Commission, President Régine Laurent says one particular moment of public testimony stood out above others.

“There’s a sentence that comes back to me: an Indigenous community said ‘excuse us, but we’ve been loving our children for thousands of years,’ Pierre told reporters Monday.

“’We want to take care of children who need us, but in our own way’ – and that is our orientation [with the report.]”

In its preliminary report, made public on Friday, the Laurent Commission, which is examining failures in Quebec’s youth protection and child welfare systems, recommends putting the best interests of the child back at the heart of all youth advocacy interventions.

This will mean giving children the opportunity to be heard, consulted about their present situation and future before deciding what will happen to them.

It also recommends immediately creating a position for a director of youth protection. His or her task would be to see to a uniform interpretation of the Youth Protection Act.

According to inquiry Vice-President André Lebon, witness testimony so far points to the need for First Nations to have “both hands on the steering wheel” when it comes to their children.

“There’s currently an illustration that those [fundamental] rights, and consideration for the culture is not respected,” Lebon added.

“This requires corrections.”

The Laurent Commission inquiry was called in mid-2019, after a seven-year-old child was found dead in a home in Granby, 80 km east of Montreal.

Complaints made to youth protection prior to the child’s death reportedly went uninvestigated.

It’s a situation that repeated itself within the Huron-Wendat community of Wendake, just outside of Quebec City, in late October.

Two children under five were found dead in a home after numerous reports to the Direction de la Protection de la Jeunesse – known as the “DPJ”- also went ignored.

Their deaths are now subject of a handful of investigations.

In response, provincial ministers said they won’t make any drastic changes until the Laurent Commission turns over its final report.

The commission was originally scheduled to deliver its final report on Monday, but asked the government for more time due to the pandemic.

Its final report is now scheduled to be delivered on April 30, 2021

When it comes to First Nations, the preliminary findings released Monday reiterate what many people feel is already common knowledge.

“Indigenous children are over-represented in youth protection, and services do not take into consideration the historical and cultural context of their language and their values,” the preliminary document reads.

According to this first report, “several calls to action have been made across diverse commissions that were based in cultural realities and access to services. The witnesses heard want us to recognize and act on the causes of overrepresentation of these populations in youth protection.”

“I unfortunately can’t give you all of our ‘recommend-actions,’” Laurent said. “What I can tell you is we support the recommendations made in the Viens Commission – that’s clear.”

The Viens Commission final report found “it is not the fundamental goal of the [Youth Protection Act] that is the problem, but rather some of its principles.”

“Based on the evidence presented, these principles put the youth protection system at odds with Indigenous cultural values, which then leads to discrimination,” according to the 488-page final report.

“It’s clear that we will take into account in our ‘recommend-actions’ the devastating effects of removing children from their communities. How can we work with communities? We want communities to work for themselves and for their children,” Laurent told reporters.

In some cases, community members are stepping up to face the current system and take control of their own.

The Innu community of Uashat Mak Mani Utenam has mobilized twice in the last two months to prevent a child apprehension from happening.

In the first, police reportedly tried to pull three children out of their grandmother’s house for placement in three separate foster homes – one over 1,000 km away.

After a prolonged demonstration by community members, the children were taken in by another family in the community.

In the second intervention, the community stopped five children from being apprehended and placed elsewhere.

“I hope these women, these mothers will continue mobilizing against these repeated violations on Quebec’s part,” said Virginie Michel, a resident of Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam who attended the demonstration.

Michel qualifies youth protection interventions in the area as “abusive.”

“Whether that’s through evaluating our capacity to act as foster parents, to care for children. They still impose too many criteria,” she explained.

“But Quebec, (Premier) Francois Legault refutes and refuses [any] advancement by going to court,” Michel added.

Quebec is the only Canadian province challenging the constitutionality of Bill C-92, the federal child welfare legislation.

Since Jan. 1, 2020, First Nations across Canada have the right to create and implement their own child welfare systems.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau just recently announced an additional $542 million so Indigenous communities “exercise full jurisdiction over child and family services.”

“This is vital to moving forward on our promise to address the unacceptable injustices that too many kids and families have faced in the care system,” Trudeau said in a press conference last week.

But Quebec, for its part, feels child welfare is a provincial issue.

Officials require extensive proof that an Indigenous-led plan is workable and can be sustained before it receives “approval” – and with it, funding.

Mike McKenzie, chief of Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam, says his community currently has three of Quebec’s criteria met.

He’s hoping to sign an intermediate agreement with the province and get the ball rolling to implement new programs – including a committee of women and elders to potentially make decisions about housing arrangements for children in need.

“What we’re asking for from Quebec in terms of agreements is to have the bare minimum to respond to our aspirations,” McKenzie told APTN News.

– With files from Sylvie Ambroise and The Canadian Press