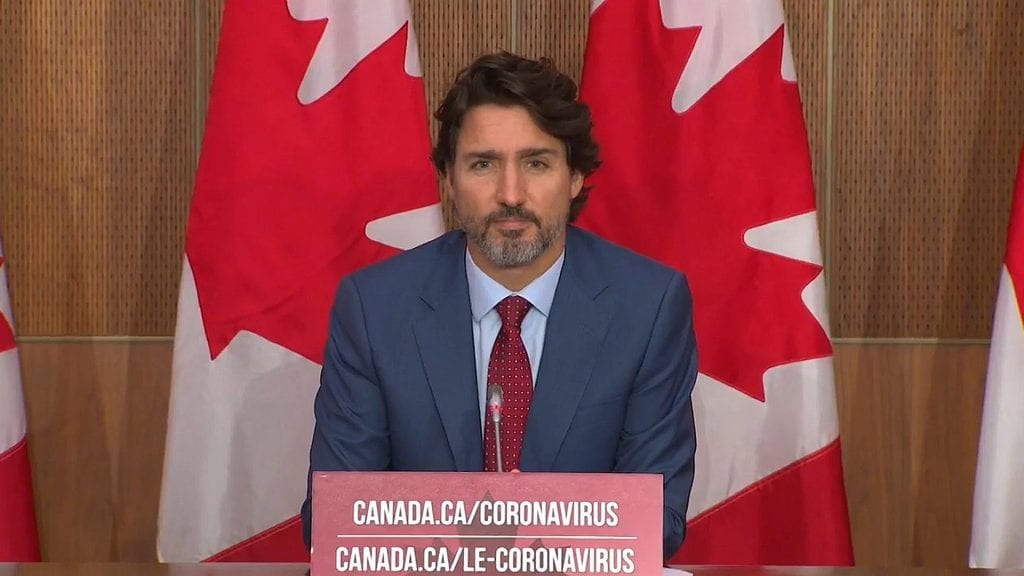

Justin Trudeau responds to calls for action after a mob vandalized a facility storing a Mi'kmaw lobster catch this week. Photo: APTN

The prime minister says Ottawa is “extremely active” in trying to de-escalate the issue that non-Indigenous fishers have with Mi’kmaw fishing rights that has rocked wharfs in southwestern Nova Scotia for the last month, responding to criticism that police haven’t done enough to protect Mi’kmaw fishers and a chief’s call for him to step in after protests turned violent this week.

“This is a situation that is extremely disconcerting and of real concern. That’s why we’re calling for an end to the violence and the harassment that’s happening,” Justin Trudeau said on Friday.

“We are expecting the RCMP and police services to do their jobs and keep people safe. I think there’s been some concern that that hasn’t been done well enough, and that’s certainly something we will be looking at very closely.”

Trudeau says he recognizes the Mi’kmaq Nation’s constitutionally protected right to fish for a moderate livelihood but adds Ottawa must ensure that a solution to the dispute “fits within an important commercial activity in the Maritimes that is fishing.”

The conflict revolves around the Sipekne’katik First Nation’s self-regulated fishery that the community launched last month, issuing their own lobster fishing licences and tags outside of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) season for that area.

The Supreme Court said in the 1999 Marshall decision that Mi’kmaq have a right to fish for a moderate livelihood under Peace in Friendship Treaties of 1760-61 but didn’t define the term.

Commercial fishers protested the operation, blockaded Mi’kmaw boats, chased them on the water and immediately seized or destroyed lobster traps. This week a 200-person mob surrounded Mi’kmaw fishers in a lobster pound and stole their catch. A van was torched, other vehicles damaged by rocks and huge mounds of frozen lobsters trashed.

Read more:

Van torched, lobsters destroyed as mob surrounds Mi’kmaw lobster pounds in Nova Scotia

Dear non-Mi’kmaw fishers: Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia have an inherent right to fish, you do not

In widely-shared Facebook videos, RCMP stand by and watch the destruction. A peace officer quickly extinguishes the van fire in one, while another shows Mounties inside the vandalized storage facility, known as a pound, discussing possible break and enter charges.

But police arrested no one. It prompted Chief Mike Sack, who a protester roughed up on Wednesday, to blast police inaction and call for Trudeau’s help.

“These despicable and racist acts by an unruly mob against a First Nation have impacted and affected Sipekne’katik in a disturbing and unsettling manner as members of my community, including myself, have been physically assaulted, harassed, intimidated, and are victims of racism and violence,” he wrote in an open letter shared online.

“I am calling upon you, Mr. Prime Minister, to uphold Canada’s laws and ensure that vigilantes are prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law, including the rescinding of fishing licences that any of these vigilantes may hold.”

Sack adds that, by not acting, the Mounties encourage further violence and that the First Nation intends to seek civil remedies against those interfering with the nation’s right to fish.

Trudeau twice dodged the question of whether he will get involved directly. He pointed to his administration’s past accomplishments when asked why Canada often comes to the table to talk land and resource rights after occupations, blockades, protests and direct action by First Nations reach crisis levels.

“We’ve seen thousands of Indigenous kids starting school years in new schools. We’ve seen a lifting of well over 90 long-term boil water advisories, many of which have been in place for decades,” the prime minister said. “We’ve seen significant progress on settling land claims and fixing historic injustices. We have made significant progress over the past five years, but there is always much more to do.”

In February, Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett flew to British Columbia to negotiate a rights and title memorandum of understanding after a pipeline blockade led by Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs resulted in country-wide protests on rail lines and other infrastructure.

At the same time, Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller met with solidarity demonstrators who stopped trains from passing through Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory located 250 km southwest of Ottawa. The crisis pulled Trudeau home from a failed overseas bid for a seat on the UN Security Council.

In August both ministers offered to meet with Six Nations chiefs after a police raid in a development standoff spurred rail and road blocks in Caledonia, Ont.

“We’re also reaching a point where it’s not just up to the federal government to be making changes along the road to reconciliation,” Trudeau continued, suggesting the provinces need to do more.

Trudeau says the feds are committed to protecting Indigenous languages, developing Indigenous health legislation and keeping kids out of care through Bill C-92, which would allow First Nations to assume jurisdiction over child and family services.

Quebec challenged C-92’s constitutionality and says the legislation infringes on provincial jurisdiction. Premier Francois Legault refuses to admit systemic racism exists in the province following the death of Atikamekw mother of seven Joyce Echaquan, 37, who live-streamed nurses hurling vitriolic racist insults at her before she died in Joliette, Que.

Trudeau says the federally-organized emergency meeting on anti-Indigenous racism in health care, which hundreds attended on Friday, is an important first step.

Miller suggested Ottawa could use its significant financial leverage over health care to fight systemic racism but retreated when asked if that includes withholding funds from provinces and territories.

Trudeau says it’s too early to determine what he might do if the provinces won’t commit to improving access to health care for Indigenous people – though he’s confident they will.