Prime Minister Justin Trudeau accepts the final report of the MMIWG inquiry on June 3, 2019. APTN file

Indigenous women and girls are not unique victims of crime and don’t qualify for a class-action lawsuit or compensation from Canada, a federal justice department lawyer said Thursday.

“Indigenous women don’t face a specific threat from a specific source,” co-counsel Christine Ashcroft told a four-day hearing to certify a proposed class-action lawsuit that wrapped up Thursday in Regina.

“Sadly, like all women, Indigenous women are at risk from family members, acquaintances, strangers and serial killers.”

Legal teams each spent two days arguing the merits of the civil suit launched against Canada and the RCMP by the Merchant Law Group of Regina.

Lead counsel Tony Merchant was confident at the end.

“I think she’ll certify,” he told reporters after Federal Court Judge Glynnis McVeigh reserved her decision and closed court.

Dianne Bigeagle

Merchant filed the suit on behalf of Dianne Bigeagle, whose 22-year-old daughter disappeared from Regina in 2007. Bigeagle is seeking $600 million for families of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG).

Merchant shared statistics that show Indigenous women comprise only four per cent of the female population in Canada but accounted for 24 per cent of homicide victims in 2015 – up from nine per cent in 1980.

He said victims’ families and communities were a unique and vulnerable group that should be recognized for harms suffered by a poor performance by Canada and the RCMP.

“This special group requires this special attention,” he said.

But Ashcroft said Merchant failed to make his case.

“What (he) proposed amounts to a second national inquiry,” she told the judge.

“We know a number of factors make Indigenous women vulnerable to violence. What this claim tries to do is blame it on the police.”

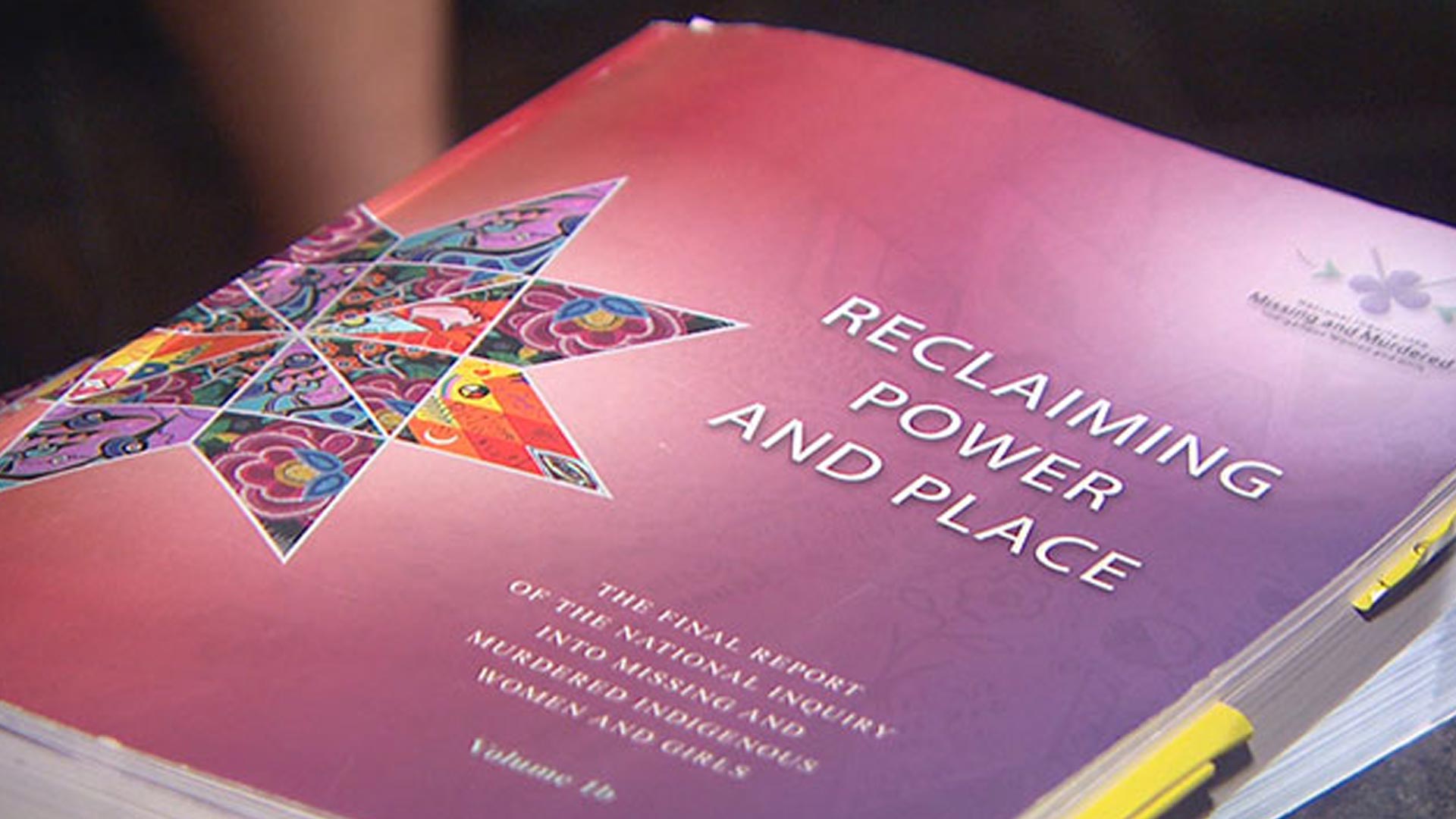

The work of the National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls, which travelled the country from 2016 to 2018 hearing from family members, agencies and even police departments about the root causes of violence, figured prominently in the courtroom this week.

Its final report said Indigenous women and girls are 12 times more likely to be murdered or go missing than non-Indigenous women and girls. And, it made recommendations for sweeping changes by governments, police services and the public.

“The inquiry said the problems are ongoing,” Merchant noted.

But federal co-counsel Bruce Hughson said Canada was working on a plan – a federal action plan – for “the last 15 months.” And remained “deeply committed” to protecting Indigenous women and girls and 2SLGBTQQIA (two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual) people – now and in the future.

“There is no evidence of that,” Merchant argued, after jumping to his feet.

Calls for action

Hughson said Canada will respond to the inquiry’s calls for action, making a class-action lawsuit moot. He also listed a number of ways RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki has committed to improving the way Mounties deal with MMIWG cases, including addressing the way officers communicate with families.

Hughson’s co-counsel Alethea LeBLanc suggested Bigeagle was not a good fit for a representative plaintiff because her daughter’s case remains with the Regina Police Cold Case Unit.

The RCMP are not investigating Danita Bigeagle’s disappearance, LeBlanc told court.

Correction: This story was update 26/09/20 to change the word ‘special’ to ‘specific’ in the headline and second paragraph.