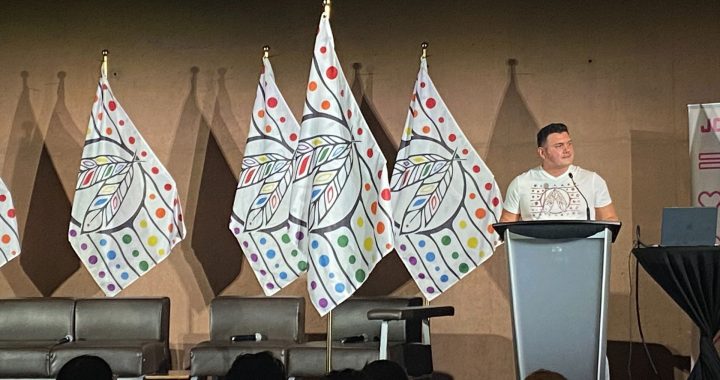

Elder Francois Paulette of Smith's Landing First Nation, is urging Indigenous leadership to use COVID-19 to prepare for impacts of climate change such as food security and increased research on the Peace Athabasca Delta. Photo: Charlotte Morritt-Jacob/APTN

People who fight to protect the environment and their communities say the province of Alberta is making a mistake by suspending environmental monitoring because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Earlier this month, the Alberta Energy Regulator ended a wide array of environmental monitoring requirements for tar sands companies over public health concerns raised by COVID-19.

The decision means that companies, including Imperial Oil, Suncor, Syncrude and Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., don’t have to perform much of the testing and monitoring originally required in their licences.

A major concern is the tailings ponds that are large pools of chemicals including benzene, acids, and silt left over from the process of extracting bitumen from the soil.

“There’s times on a good hot day I would smell Fort McMurray from here,” says Dënesųłiné Elder François Paulette.

“There are times when I am on the river – up the river – and in the evening when it is totally calm you could see a haze on the river, that’s smog.”

The Smith’s Landing First Nation knowledge holder has travelled the world and shared insight on Indigenous and treaty rights, healing, spirituality and environmental protection.

His band has been forced to postpone on-the-land monitoring projects because of COVID-19 restrictions.

It couldn’t come at a worse time.

This spring, the Peace and Athabasca rivers saw high water levels which resulted in flooding and evacuations of residents in Fort McMurray and Fort Vermillion. Oil sand tailing ponds which are in close proximity to waterways heightened Paulette’s concerns about environmental contamination.

“If those tailing ponds ever flushed into the river we would have a big problem. No legal defence is going to clean it up, clear it up. Water is essential to everything living,” he said.

The Peace Athabasca Delta, located in northeast Alberta, is the largest freshwater inland river delta in North America. It resides in Wood Buffalo National Park, a UNESCO world heritage site, home to wood bison, fish and migratory birds and Elders like Paulette who live in remote communities within the park.

But it’s downstream from the oil sands that have impacted the way of life for Dene, Cree and Métis who live, travel, trap and hunt in the area.

“You would very seldom see a muskrat in the river. If you did, ‘I would say thank you to the muskrat.’ The muskrat is more vulnerable to pollution,” Paulette said.

Jason Nixon, minister of Environment and Parks in Alberta, said the possibility for a breach in the tailing ponds is “misinformation.”

“No tailing ponds have been breached and there is no imminent risk of flood water breaching any of the tailing ponds in the oil sand region,” Nixon said at a press conference.

Jesse Cardinal begs to differ.

She’s spent years demanding energy companies, provincial and federal leadership to take a holistic look at the environmental impacts caused by the tar sands.

She’s from the Kikino Métis Settlement, the interim executive director of Keepers of the Water, an Indigenous-led conservation group.

Cardinal hosts workshops on how to protect watershed lands for ecological, cultural, and Indigenous health and social wellbeing.

“This morning I saw hundreds of geese flying north. I was thinking of one of the presentations I do, is a picture of a pristine lake in the mountains, which is bright, blue and clear and then a picture of the tailings pond and you can’t tell the difference,” Cardinal said.

Recently, around 50 birds died after landing on tailing ponds at the Imperial Oil Kearl Lake site.

While a full breach in dams that hold tailings ponds has not happened, Cardinal has repeatedly questioned why an oil company’s emergency clean-up plans are not made public.

“I’ve been at meetings where companies have said that it is similar to showing where the pipelines are, for public safety, which doesn’t seem right. A lot of people depend on the tar sands for jobs not because they want to but because it the only option. I view it as an abusive relationship with a colonial power,” she said.

Cardinal expressed frustration with Alberta Premier Jason Kenney and his United Conservative Party (UCP) government undoing work of the previous NDP government.

“I liked that the NDP had a huge climate change program. They were trying to get big renewal energy project going and include Indigenous people where they would be a full out owner of these huge scale renewable projects or an equity partner where they could buy shares to these projects,” Cardinal said.

Even with hopes for diversification, the issues of toxic tailings are not going away any time soon.

Jule Asterisk, interim executive director of Indigenous conservation group “Keepers of the Athabasca,” has spent years monitoring tailing management plans within the watershed.

“It’s just a shame we have to do the work of government. The bitumen industry is using the ground and the ground water as a filter for the tailings . The tailings are placed on sand they don’t even have to use compacted clay like a municipal landfill would. It’s porous,” Asterisk said.

In 2018, a complaint regarding the potential for leaking tail ponds was filed with the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, (CEC) a NAFTA working group created after the government of Canada, USA and Mexico signed the North American Agreement on Enviromental cooperation in 1993. The CEC says it began working on the complaint immediately.

Keepers of the Athabasca worked with hydrologists to develop new technology by the Alberta EcoTrust Foundation and Society of High Prairie Regional Environmental Action Committee (REAC) to track the pollution. The new tool examines 3D images of the subsurface area around the tailing ponds associated with the bitumen mines of northeastern Alberta

“You need to be able to prove this is going on. The leapfrog model tool called the data visualization tool, it allows us to take a cross section of the ground and move forward and backward through it. You can see where all of the wells, infrastructure is and where potential leaks might be,” she said.

Asterisk believes local communities could use the new leakage visualization tools to pinpoint contamination.

Studies have confirmed what Indigenous conservation groups have known for years, that oil sands tailings are seeping into groundwater and the Athabasca River.

“What we learned with the team of hydrologists who worked with us on the Athabasca basin tailing ponds and impacts on aquifers study, was that those tailing ponds are continuously leaking through the ground water and coming up in the Athabasca River and it’s common knowledge, known by government and industry since 1981,” Asterisk said.

Keepers of the Athabasca has been waiting for the initial factual record in the Alberta Tailings Ponds publication to bring forward to the Alberta government.

APTN News reached out to CEC and received this email statement.

“The initial factual record in the Alberta Tailings Ponds submission has been sent to the CEC Council for a vote on its publication. We expect that vote will take place by July 14, 2020. If the Council votes to authorize the publication, the CEC Secretariat will upload the final factual record to submission registry shortly thereafter.”

Back in Smiths Landing First Nation, Paulette is urging all levels of government to put environmental preservation at the forefront as plans to adapt to a new normal are formulated.

“When Canada announced the climate emergency resolution in the house, other First Nations looked at that as good. It’s good to make that announcement, but now we need to prepare. To adapt to clean energy. To prepare for food security, the health of the people,” he said.

As Paulette suggested, the federal call of a climate emergency was followed by a motion in the House of Commons that was non-binding, but those who are feeling the effects first hand want action now.

But he’s not seeing this take hold on the ground in Alberta – where his people will be affected if nothing is done.