Compensating First Nation kids harmed by the underfunded child welfare system will cost the federal government billions less than Ottawa originally estimated, Canada’s independent spending watchdog says.

Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) Yves Giroux calculates it will cost anywhere between $900 million to $2.9 billion to comply with a 2019 Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) order to compensate First Nation children and families for harms suffered at the hands of a discriminatory system.

“The public’s key takeaway,” Giroux told APTN News, “should be that the government has taken a very broad interpretation of who should be eligible for compensation, whereas a more literal reading of the ruling suggests that compensation does not need to be that expensive.

“A reading by what is assumed to be a reasonable person suggests that it’s not as expensive as the government suggests to settle that CHRT ruling.”

According to the report, ISC anticipated 125,000 people are eligible for compensation that would total $5.4 billion.

But an affidavit filed by Sony Perron, the associate deputy minister of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), said complying with the compensation ruling could cost the government up to $8 billion. A figure that would cause “irreparable harm” to the country, the government said.

The PBO, although using the same data, came up a much lower eligibility range of 19,000- 65,100, reaching an estimated cost that is billions less than the government’s figure.

These numbers came from a different interpretation of who is eligible, Giroux explained.

“The reason our numbers are lower is because we interpret the ruling literally. So, a child has to have been placed outside of his home, family and community. Whereas ISC went for a much broader definition: either outside of their home or outside of their family or outside of their community.”

The tribunal ruled in 2016 that the Canadian government discriminated against First Nation kids by “willfully and recklessly” underfunding the child welfare system on-reserve and in the Yukon, creating an incentive to scoop kids from their families and place them in foster care.

In 2019, the tribunal awarded a maximum compensation of $40,000 to each victim and certain family members who also suffered. Canada is currently seeking a judicial review of this ruling in federal court.

But that historical ruling was nearly a decade in the making.

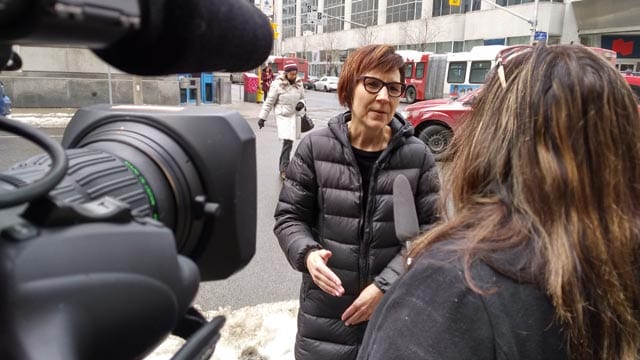

(Cindy Blackstock speaks with reporters. Photo: APTN)

Cindy Blackstock’s First Nations Child and Family Caring Society (FNCFCS) and the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) brought the human rights complaint forward in 2007.

“The most important takeaway,” Blackstock said of the report, “is that Canada can pay this compensation. It’s not as complicated as they made it out.”

The report, which is called First Nations Child Welfare: Compensation for Removals, also discussed the two class-action lawsuits that the government is facing on this issue.

AFN brought the newest lawsuit forward, which is worth $10 billion. The other lawsuit is worth $6 billion and was filed by Xavier Moushoom and Jeremy Meawasige.

On March 6, Canada’s lawyers asked for a “joint case management conference” due to the “substantially similar issues” raised by the two cases, according to federal court filings.

“We are in ongoing discussions with the AFN about combining our efforts. Those discussions are confidential,” David Sterns, a lawyer for Moushoom and Meawasige, told APTN on March 20.

The government has argued that by awarding a large settlement to thousands of people, the tribunal has stepped outside of its mandate and essentially approved a class-action suit against Canada. Lawyer Robert Frater, who is leading the judicial review for the government against the tribunal said what the tribunal has done is a “class-action by another name.” No date has been set for the judicial review.

Read more:

AFN sues Crown for $10-billion in newest First Nation child welfare case

Federal Court strikes down request from Canada to have human rights tribunal ruling put on hold

The PBO stressed that class-actions and the tribunal order are separate, however.

“Canada cannot void the CHRT’s order simply by settling a class action. So, the framing of a class action settlement as an alternative to complying with the CHRT decision still relies on Canada having that order quashed through judicial review,” the report said.

NDP MP Charlie Angus asked the PBO to prepare this report in December 2019. He told APTN that the longer it takes to compensate kids and their families, the higher the cost will be.

“Look at the actual numbers. They are less than the government claims. If you look at what the PBO has laid out, it’s probably a more reasonable approach, and so just do the right thing and pay it because the longer you delay the more it’s going to cost,” he said.

“Put the kids first. This is a good roadmap to finding a solution.”

The report also discussed the topic of rising costs.

“ISC’s estimates also explore the implications of it taking until 2025-26 to resolve the claim,” wrote the PBO.

“Under that scenario, ISC’s preliminary cost estimate rises to $6.7 billion. The PBO’s estimate rises to $3.7 billion under the scenario where all children removed from their home, family, and community for reason other than abuse are eligible.”

ISC would not say why they are taking the “broad interpretation” pointed out by the PBO’s report, only that they are “reviewing its findings.”

“The report highlights the complexities of the task at hand and the number of variables we need to get right in order to be able to advance fair compensation,” said spokesperson Vanessa Adams.