Just weeks after moving in, Lake St. Martin First Nation community member Bernice McKenzie began hearing a noise in her master bedroom.

“At the beginning it was slow…but now it’s just like a water tap,” she said.

McKenzie moved into her new home on March 2, 2018.

“I was excited. I was really happy,” she said.

(Bernice McKenzie at home in Lake St. Martin First Nation. Photo Josh Grummett/APTN Investigates)

Lake St. Martin First Nation was forced to evacuate in Manitoba’s 2011 flood, and members lived in Winnipeg hotels and other temporary homes for years after.

In the last couple of years, community-members have been re-establishing their relocated community and moving into new homes.

But after returning, McKenzie was dealing with a different kind of flood. One that never stopped, and came from a pipe inside her wall.

McKenzie said the water just kept running, except for six weeks earlier this year, when the main valve was shut off so the band could fix the leaky pipe.

But unfortunately the pipe was never repaired, so she went back to having the water on.

And as of mid-September 2019 when APTN Investigates went out to look at her situation, water spray from a pipe was keeping a spot on her master bedroom drywall soaked, wetting her floors, and pouring into the crawlspace below.

Watch a video of Bernice McKenzie’s basement

Water pours into the crawlspace of Bernice McKenzie’s home in Lake St. Martin First Nation. Video Christopher Read, APTN.

It was only after McKenzie contacted the band office to let them know she had shown APTN Investigates the situation in her home that someone came out to repair the pipe.

We contacted Lake St. Martin First Nation Chief Adrian Sinclair and told him what our story was about, but he didn’t get back to us when asked for comment.

McKenzie’s case might be on the unusual end of the spectrum, but her never-ending leak is rooted in the never-ending on-reserve housing crisis we hear about regularly in the news.

On-reserve housing expert Sylvia Olsen says the struggle to effectively manage housing is a recurring theme in many First Nations.

Olsen was a housing manager at Tsartlip First Nation in British Columbia for a number of years, and more recently wrote a history of on-reserve housing for her PhD dissertation at the University of Victoria.

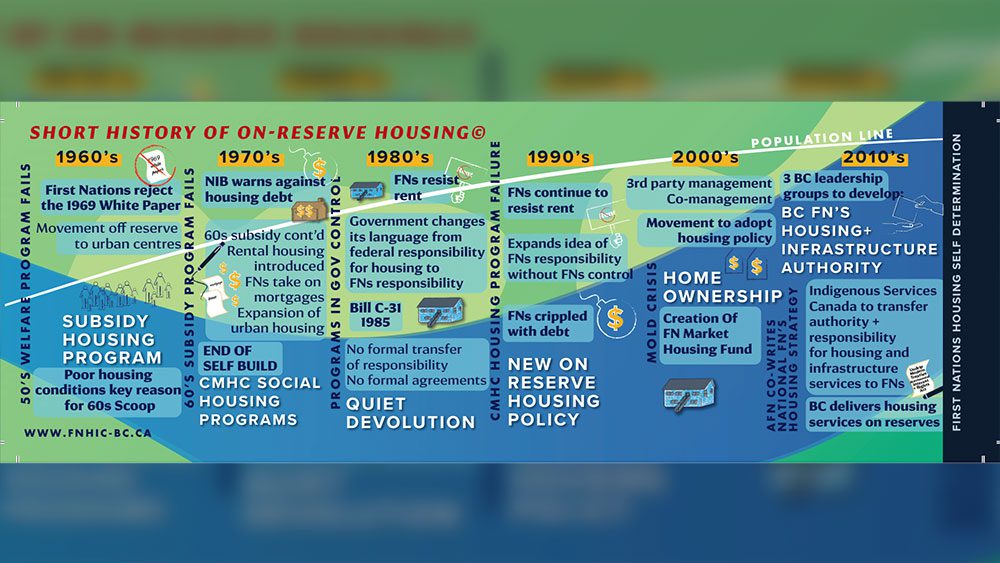

(APTN Investigates reporter Christopher Read observes Sylvia Olsen as she shows him her history of on-reserve housing in graphic form. Photo: Rob Smith, APTN Investigates)

For years, the management of reserve-housing in Canada was a top-down affair with the federal government in charge, she said.

Over the years the federal government has divested some of the responsibility for housing management to First Nations themselves — but Olsen says getting someone in the band who is up to speed on how to manage housing is a challenge many bands are poorly equipped to deal with.

“So a lot of the trouble in a lot of those First Nations is they don’t have that person in the office that actually is trained and knows how to do that,” she said. “And they have an enormous job and I know a lot of the First Nations that … it’s the chief’s job – or some random guy in the office’s job – or an elected official’s job. And housing management is a much more complex thing to do than just ‘here take this on as well as whatever else you’re doing.’”

To Olsen, the history of on-reserve housing is largely one of failure.

The government’s involvement in housing began in earnest in the midst of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

For non-Indigenous Canadians, the developing housing system allowed for people to borrow money — and over the years as people paid off mortgages, their homes would accrue value and generate wealth.

But instead of generating wealth, Olsen says, the housing programs set up on-reserve generated poverty.

“What government set up there, rather than new opportunities to borrow money, ways to insure your loans … what they did on-reserve is set up a system of how to get housing materials to build houses after a welfare model.”

And the creation of this separate housing program for Indigenous people was largely a result of the Indian Act, which prohibits the seizure of on-reserve assets.

“Because on-reserve you couldn’t borrow money,” said Olsen, “So now it had to be a government supply of housing.”

Furthermore, Olsen says that the system for on-reserve housing was never meant to work.

“You and I could figure out here in two minutes that a welfare delivery model to an entire population simply can’t work. And it didn’t,” said Olsen.

And the reason for rolling out a system that couldn’t work?

“Canada completely and utterly assumed that Indigenous people were dying out,” said Olsen. “So the root of this system…is based in the idea that Indigenous people were not going to survive as a people so that this could be more like a temporary fix.”

(Sylvia Olsen’s history of on-reserve housing in a graphic timeline form. Provided by Kerry Black of the BC First Nations & Infrastructure Council. Graphic design by Desiree Bender)

According to Olsen, another factor in the long term failure of government-run reserve housing is the nebulous legal status of home ownership.

In the Indian Act, a reserve is defined as land held in trust by the crown for the band.

So, if the Crown owns the land, who owns the houses?

“Who owns the houses on reserves is still a question,” said Olsen. “Now the government might say…the First Nations own those houses, but in truth it’s a disputed question. So – who owns the houses, is it the government or the First Nation is disputed – and on many, many, many if not most First Nations, who owns the house, the person who lives in it or the First Nation is also disputed. So this system…is not very systematic at all and there’s a whole lot of these really fundamental questions that are left unanswered, which is why there’s a lot of chaos in how to manage this housing stock.”

And uncertainty about ownership begets uncertainty about responsibility.

In Bernice McKenzie’s case, she told us her home is owned by the Lake St. Martin band – and for that reason she hasn’t acted personally to solve the leak issue.

“If it was my house then you know I would have had that done. But these are band owned houses – and they’re insured,” said McKenzie. “So I’m not sure.”

Devolution is another factor that has negatively affected the management of on-reserve housing, according to Winnipeg-based Red Seal carpenter Alan Isfeld.

Isfeld is a member of Waywayseecappo First Nation, a former building inspector for the city of Winnipeg, and a former building materials salesman. He has worked extensively on reserve construction projects.

And for Isfeld, a devolutionary move by the government in 1996 is key to understanding many of the problems affecting Indigenous housing today.

“Prior to 1996 all houses built on reserve and off reserve were subject to the same mandate, said Isfeld. “In other words you have to have journeyman tradesmen building these homes – you have to have bonds – you’ve got performance bonds, material bonds and everything else.”

(“… you’ve got people who aren’t qualified,” says Red Seal carpenter Alan Isfeld. Photo: Josh Grummett/APTN Investigates)

Isfeld saw first-hand what happened after 1996 when many bands were handed the responsibility of making sure building codes were met.

“Everything went to hell in a handbasket so to speak because now you’ve got people who aren’t qualified who were never given the qualifications or weren’t properly informed of what they were taking over,” said Isfeld.

APTN Investigates contacted the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation for confirmation of how the “on-reserve non-profit housing program” works.

“CMHC is not a regulatory agency,” the federal agency told us in an email. “CMHC has no mandate or authority to enforce building codes or standards.”

“The First Nation is responsible for enforcing compliance with building codes and standards,” the email continued.

The agency also said it requires the First Nation to certify building code compliance at three stages in the construction process.

But according to Isfeld, this process is not about assuring quality.

“That’s to advance CMHC’s payments, not to advance the quality of construction on the house,” said Isfeld. “There’s a difference. So there’s no one out there right now that is guaranteeing the quality of the construction of the homes built in most reserves.”

And Craig Blacksmith, CEO of Dakota Plains First Nation in Manitoba echoes Isfeld’s characterization of the inspections.

“The inspectors that come out and inspect do superficial inspections,” said Blacksmith. They don’t actually get into the construction of the house. It’s more of an inspection for a progress payment.”

Isfeld also pointed to the transport and storage of building materials as another area where quality control has suffered.

He noted that northern communities accessible only by ice road have faced particular challenges.

“They travel up on a winter road and because moisture splashing on the building materials and they’re offloaded on the ground and they sat there for three or four months before the construction season actually starts in those communities so the houses that they’re building are basically instantly subjected to mould,” said Isfeld.

And while some would argue that the government is attempting to operate in a nation-to-nation manner and thus leaving it up to First Nations to determine whether standards for proper transport, storage and construction are followed, Isfeld doesn’t see it that way.

“The chief and councils – I think – were blindsided because they envisioned now that they were in control of something when really they weren’t,” said Isfeld.

Isfeld believes the government didn’t support the transition properly and First Nation communities were not given the opportunity to acquire the knowledge and skills needed to match the quality controls enforced elsewhere in Canada.

“Well I feel it’s a betrayal,” said Isfeld. “A betrayal of trust.”