On the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, entire generations of people have grown up using a ferry barge or walking across unsafe ice roads to enter or leave the community.

The community sits on the Manitoba-Ontario border.

At the turn of the century, an aqueduct was constructed in order to provide the city of Winnipeg with drinking water.

When that happened, it created a canal that turned the community into a man-made island.

Ainsley Redsky, 16, is just one person from Shoal Lake 40 who’s lived this way.

“I felt very isolated from everyone else,” says Redsky.

She has vivid memories of making these difficult trips on the barge with her family.

(Ainsley Redsky describes riding the ferry barge during the winter season when several boats would have to pull it when it breaks down. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

“If the ice froze over you could walk on it and that was very scary. You could hear the crackling under the ice. It felt like it was going to break underneath you.”

Since there is no high school in the community, Redsky lives with a different family in nearby Kenora, Ont. so she can attend school there.

During the late 1970s, the community put a barge called Amik II into service to transport people and vehicles to Shoal Lake.

The flat-bottomed ship would transport people to the neighbouring community of Iskatewizaagegan First Nation, known as Shoal Lake 39 to reach the highway — a significant detour.

Decades old drinking water advisory

(Jugs of water are purchased from Kenora for Shoal Lake members because of their contaminated water. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

Shoal Lake 40 has lived under a drinking water advisory for the past 22 years. It’s because of cryptosporidiosis, a disease caused by microscopic parasites, and not having a new water treatment facility.

Today, truckloads of clean water are brought into the community from Kenora. The community spends anywhere from $80,000 to $100,000 per year on water, and then gets reimbursed by the department of Indigenous Services Canada.

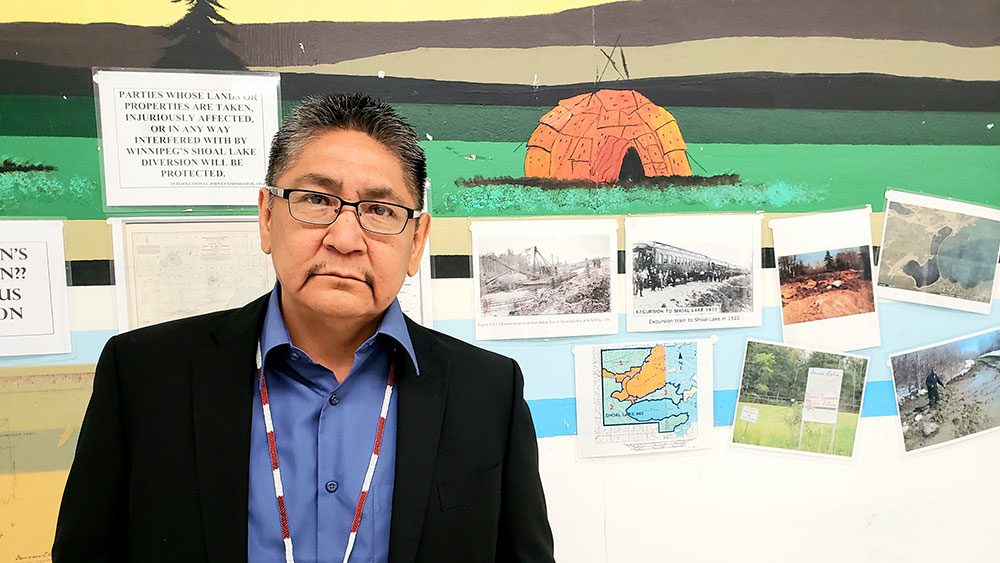

(Chief Erwin Redsky standing inside the Canadian Museum of Human Rights Violations in Shoal Lake. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

Chief Erwin Redsky, making a point about the hypocrisy of the situation, says his community opened their own museum to do with human rights soon after Winnipeg opened their $351-million Canadian Museum of Human Rights in 2014.

Inside the gallery, called Museum of Canadian Human Rights Violations, are archival photos, documents and newspaper clippings about the community’s plight.

It’s a history the road can change, the chief hopes.

“What Freedom Road means to our community, it’s life, it’s freedom, it’s all those things. It’s a hundred year old story that we’ve been fighting for,” he said. “Our lands were taken, stolen, and we were placed into a man made island to live in unacceptable conditions.”

In the spring of 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited the community as part of a documentary project for Vice Canada.

While there, Trudeau carried large jugs of bottled water and delivered them to homes, promising better relations with Indigenous peoples.

Read More:

Shoal Lake 40 is another step closer to being hooked up to the outside world

Shoal Lake 40 inching closer to ‘Freedom Road’ completion

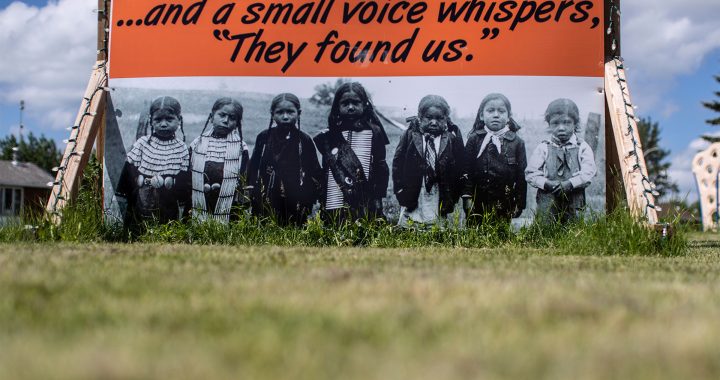

(A sign posted by the city of Winnipeg during the mid-1970’s prohibiting Shoal Lake members from accessing their own land. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

Preparing for Freedom Road

Now, after years of campaigning, political ping pong and much delay, Shoal Lake 40 is finally connected to the mainland.

Aptly named as Freedom Road, it is a 24 kilometre, year-round unrestricted road connected to the Trans-Canada Highway.

(Many residents feel a sense of relief because of Freedom Road, no longer will they have to trek across unsafe ice during the winter season to get their basic necessities. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

Construction began in July 2017, and it is now completed and officially open. As part of a tripartite agreement to finish the road, $15-million was paid for by the federal government and $7.5 million from the province of Manitoba and the city of Winnipeg.

(Prior to the barge, community members used small boats and canoes to travel across the water to get to the main highway. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

Read More:

Construction begins on Freedom Road to Shoal Lake 40

Roxanne Greene, the community’s economic development officer and a long-standing activist has been working tirelessly to raise awareness about her community’s conditions and the need to be connected to the mainland.

(Roxanne Greene says she is still in disbelief that Freedom Road is finally completed, and how it demonstrates the community’s resiliency. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

“As a band we’re looking at developing an economic hub on the highway, so that would be a corporation or a band owned business,” said Greene.

Greene says they also want community members to think about individual businesses.

But she also wants them to be wary of negative outside influences.

“We don’t want to see our community to be taken over by different kinds of drugs, so we’re preparing for preventative measures.”

For Ainsley Redsky, Freedom Road means the possibility of not having to live with virtual strangers in Kenora to attend high school.

She can only hope for those who come after her will be able to live at home while attending school.

With Freedom Road also comes a new water treatment facility expected to be completed by December 2020.

A time to celebrate

Celebrations for Freedom Road kicked off and runs until Thursday this week.

Fish fries, helicopter rides and live bands are part of the festivities.

(Shoal Lake 40 members preparing picnic tables for the Freedom Road celebrations. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

“It’s crazy to think about how far we’ve come, to have that road and to be able to go places as a family, it’s amazing,” said Redsky.

For more information about the Freedom Road celebrations you can go to: Shoal Lake Celebration