Roger Lewis strolls down a walkway along the shoreline in Digby, Nova Scotia.

The Mi’kmaw archaeologist is looking for the remnants of an old Mi’kmaw campsite he found 20 years ago. A place his ancestors lived up until the 1940s.

“There’d be little fishing camps all along down through here,” says Lewis. “You wouldn’t see evidence of that now.”

He leaves the trail, picking a path through the trees and overgrown brush.

“This would’ve been a pretty flat, dry area consistent with where they would have had their little encampments,” he said.

For a day in late February, it’s unseasonably warm.

“It must have been a comforting place because you can hear the water, small little waves hitting up against the shoreline. A bright sunny day,” says Lewis. “It’s almost like we were meant to be here today.”

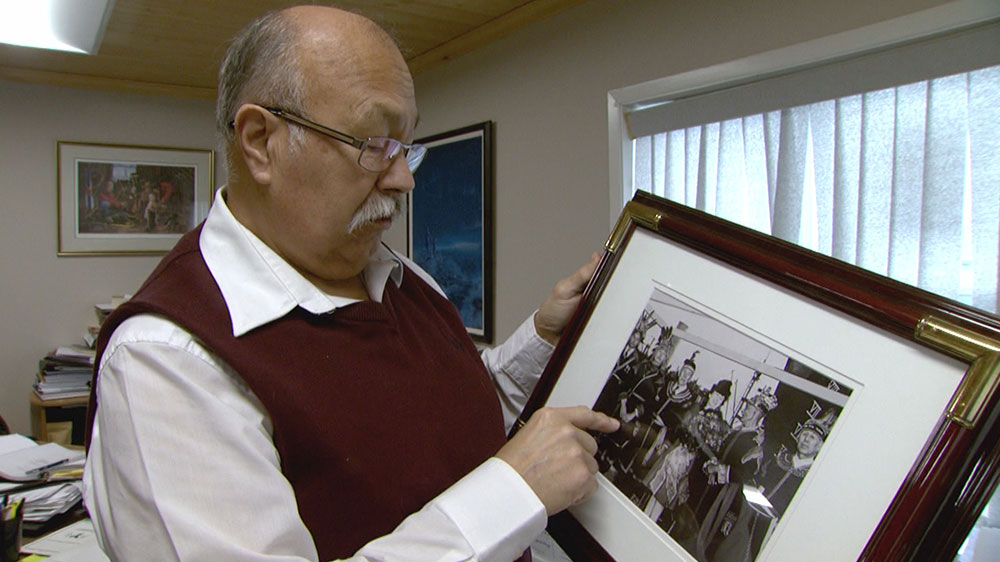

(‘There’s a history of failure when you try to relocate populations,’ says Roger Lewis. Photo: Trina Roache/APTN)

Lewis’ family was forced to move during centralization in the 1940s.

At that time there were 2,200 Mi’kmaq living in 45 reserves and settlements spread throughout the province.

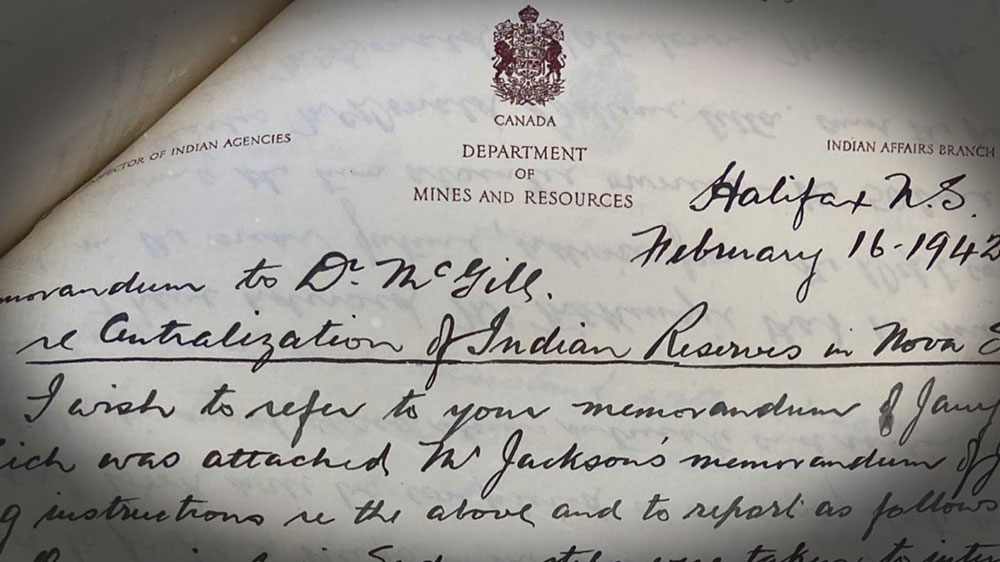

In 1942, Indian Affairs enacted a policy to relocate the Mi’kmaq to just two reserves – Eskasoni and Shubenacadie, known today as Sipekne’katik.

“If they centralize them far enough away from the cities or the towns, then we’d be out of sight, out of mind,” says Don Julien. “It was almost like we disappeared. We were, like, invisible.”

Julien is the executive director for the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq. In the 1970s, he was a researcher for the Union of Nova Scotia Indians. He interviewed Elders about centralization.

“I said, ‘what made you move? What were some of the promises that the government gave them?’” Don recalls. “And they mentioned, ‘All the Indian agents told us that houses will be so complete. All we have to do is turn the key. We have promises for employment.’”

(Don Julien, executive director for the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq, holds a photo of his grandfather, the late chief Joseph Julien, who he calls one of the “rebels” who fought Indian Affairs’ centralization policy. Photo: Trina Roache/APTN)

Jobs, houses, education, and healthcare. The Mi’kmaq were enticed to move by promises that didn’t materialize on reserve.

Shirley Anne Taylor was four years old when her family relocated to Sipekne’katik.

“We got to the house and as we got there, we got out of the car and there was no lights, no bathrooms, just a shell of a house,” says Taylor. “I remember looking around the house and seeing cracks in the ceiling.”

Taylor remembers her wonder as a child, being able to see the stars through those cracks in the ceiling.

“And then it would rain and we would yell, ‘Hey, Mommy, it’s raining.’ So mom and daddy would come upstairs and move our mattresses around so that the rain wouldn’t hit us.”

In Eskasoni, some families lived in tents through harsh cold winters because Indian Affairs’ promise of housing was not borne out.

And though centralization wasn’t officially forced, records show Indian Affairs used “our powers of persuasion,” and threatened enfranchisement, so Mi’kmaq who didn’t move might lose Indian status and services.

Julien recalls an Elder telling him, “He said, ‘The Indian agent and RCMP officer helped us load on the truck. And as we were leaving and they burned our house.’ So that discourages [us] from moving back.”

It’s a story echoed by other Elders, many of whom have since died. Indian Affairs would demolish their houses, making it difficult to return.

Mi’kmaw leaders, including Julien’s grandfather, Chief Joseph Julien, and Chief Ben Christmas, fought the relocation program.

In a position paper, Christmas called centralization “a great instrument to beat the Indians to submission.”

There’s not a lot written about the centralization of the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia. And much of the information on it is based on the work of Lisa Patterson.

She’s retired now, but Patterson spent her career as a researcher and analyst, specializing in Indigenous issues and history. In 1980, she set out to do her master’s thesis and asked the Union of Nova Scotia Indians what research would be useful.

“They were quite quick to tell me that centralization was something that had happened, and they never understood why this relocation scheme was attempted during the Second World War,” said Patterson.

“Essentially they said, we don’t know why the government did this. We don’t know what they were trying to accomplish. It made a lot of people unhappy.”

Patterson spoke with Elders and combed the archives for Indian Affairs’ records; memos, documents, correspondence, and field reports dating back to the early 1900s.

In her thesis, Patterson sums up the goals of Indian Affairs: “By collecting them at two central locations, the government expected to reduce costs for Indian welfare, education and health care; ease local complaints; and give Indian Affairs, the clergy and the RCMP greater control over Indian life.”

In a 1947 article in The Halifax Herald, the Indian agent “refers to his office as the confessional,” and “says the chief object of the federal scheme is to encourage Indians to care for themselves.”

The need for “close supervision” comes up again and again in the archival records for the “group of Indians we are seeking to rehabilitate.”

Patterson says saving money for the department by reducing the number of Indian Agents from 19 to two was a main goal of centralization.

But the records reveal a preoccupation with illegitimacy, and concerns about the Mi’kmaq living close to cities and towns, which was necessary for employment and access to markets to sell their woodworking and basketry.

At a Joint Committee of Indian affairs in 1947, a department spokesperson said, “At the time is appeared to be the only thing we could possibly do. Complaints came from the homes of White residents, where we have these small groups of Indians, about the moral relations, the temptations besetting their sons…it was really very, very disturbing.”

“We did not want to be put on the reserves,” says Taylor. “That’s how they could control us. They treated us like animals.

”We are not animals. We are human beings.”

(Mi’kmaw Elder Shirley Anne Taylor lives in the Sipekne’katik First Nation in Nova Scotia. Her family moved there when she was four years old during centralization. Eight decades later, her vivid memories of that time still bring up strong emotions. Photo: Trina Roache/APTN)

By 1949, Indian Affairs abandoned its relocation efforts in Nova Scotia. The promises of jobs didn’t pan out. Welfare rates quadrupled within a decade.

“The conditions weren’t there, the support wasn’t there, the people weren’t there, the materials weren’t there,” says Patterson. “It was doomed from the start.”

“There’s a history of failure when you try to relocate populations,” says Lewis. “You just can’t do it.”

When Lewis first found his ancestors’ camp in Digby 20 years ago, he discovered a remnant of a well, and middens where the Mi’kmaq dumped their shells and other garbage, and an old bottle dated 1929, the year his father was born.

“And but to come back here, the initial time for me was an emotional experience because I’m standing someplace where my father, my aunties, my grandmothers, my great grandparents all lived and had a connection to,” says Lewis. “So I’m here again today.”

No one walking by would ever know the Mi’kmaw connection to this place, overgrown and eroded.

“It’s a chronology, a history they never hear about,” says Lewis. “It’s not shared with them, not in the public school system, in other places.

“So it’s kind of a sad end to a legacy that’s thousands of years old. It’s kind of an empty space now, empty space because there’s no one there. But spiritually, emotionally, it’s not.”

It is sad how our First Nations lived. AS it happened here in NL. For our ancestors were forced to live on reserves and many would not say who they were because they would be beaten and what was so bad is that many women were raped while while men went off to war and some were forced to go to war. Many people didn’t didn’t tell that they had young boy who were 14 and 15 sent of to war.They had farms,logging,fishing and hunting, but in the years to come, the white took there land and they had to listen and ordered by law to give up there way of life. Many would not give there actual name and took a name of a English person and many paddled ther way to NS,NB and down along the East coast of USA. So after putting them on reserves, the living conditions were very bad and Canada made there laws of all Canadian’s.Even today our people have to fight for our rights and to protect mother earth, while many are destroying the land and waters. Through oil and gas,mining and no health for many.Hopefully in the years to come it may differ, but i fear it will only get worst.