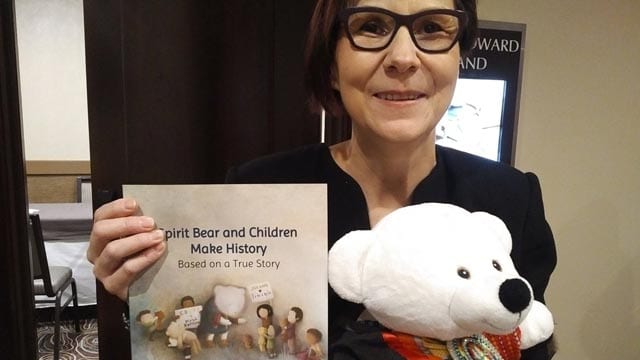

Ashley Dawn Back in Ottawa. She's a plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit against the government. Photo: Brett Forester/APTN

Ashley Dawn Bach drinks tea in a loud corner of a coffee shop in the heart of the nation’s capital. Businesspeople chatter in the background and, not far away, politicians come and go on Parliament Hill.

You wouldn’t know it by her smile or her positive attitude.

But Ashley is a plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit that wants to win $10 billion from the government for its discriminatory underfunding of the First Nation child welfare system on reserves and in the Yukon.

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) filed the suit on Jan. 28. It still needs to be certified by a court. The government has until the end of the month to file a statement of defence.

“Year after year, decade after decade, generation after generation, the Crown has systematically discriminated against First Nation Children because of their race, nationality and ethnicity and created a Removed Child Class,” wrote lawyers from Strosberg Sasso Sutts LLP in the statement of claim.

The lawsuit seeks damages for harms resulting from the “willful and reckless,” discriminatory underfunding of the system as well as the Crown’s “egregious” failure to comply with Jordan’s Principle. It also includes a family of the removed child class.

Bach says she’s “very privileged” to represent the class in this massive legal undertaking.

“It’s a big responsibility, a little intimidating,” she tells APTN News in an exclusive interview.

“I think I’m further down my healing journey than a lot of people. I’m able to talk about this stuff. I was able to go through my files – and it’s not like it didn’t have any effect on me – but I was able to read through and see what happened.”

Her healing journey was long, and it’s not over.

Ashley was born in Vancouver and removed at birth from her mother, a member of the Mishkeegogamang Ojibway First Nation in northern Ontario. She was placed in a non-Indigenous foster care home in Langley, B.C.

She left that “hostile environment” at 18, according to the statement of claim. Since then she’s visited her First Nation and done her best to reconnect with her family and culture.

She now has a university education and a promising career in Ottawa.

When she isn’t working full-time as a policy analyst, Ashley spends the “vast majority” of her time advocating for youth in care. She’s the former president of Youth in Care Canada and remains on the board. She’s a McGill University alumnus completing her master’s degree online.

Read more:

AFN sues Crown for $10 billion in newest First Nation child welfare case

Documents suggest Canada paid millions more than admitted to fight Cindy Blackstock

How many First Nations kids are in care? Canada is trying to figure that out now

Bach wants Justice Canada’s lawyers and those whose lives were not affected by the underfunding of on-reserve child welfare services to understand the impact and extent of the loss.

“It’s important for them to understand just how deeply being removed and placed into care affects people.”

Ashley never met her maternal grandmother and some of her uncles that have passed away, she says. She lost family, language, missed out on ceremonies.

“I’m an adult now, and those are things I don’t think you can necessarily go back and repeat. As well, language is a huge one, because my First Nation – and a lot of northern communities – speaks Ojibway.”

She lost her connection to the land, which she says she struggles to restore.

“It’s not the same as growing up on your territory, learning about the animals that are there, learning the traditional knowledge, learning the skills to survive in the bush. Those are things that can’t be replaced, and I’m hesitant to put a dollar value to it because it’s so much loss. That’s why I really hope that this case will change the system, so that other kids aren’t going to experience that sort of loss.”

The compensation is only part of a search for justice, she says.

“But to me what’s even bigger is the request to change the system, to stop discriminatory funding and resources for First Nations child welfare.”

Love and ceremony

Ceremony and love brought Karen Osachoff back from the brink.

She’s a member of Pasqua First Nation in Treaty Four Territory, what is now southern Saskatchewan. She and her sister Melissa Walterson are also plaintiffs in the suit.

Melissa is a member of the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation in Manitoba. The claim argues that she lost “love, care and companionship” due to the severing of the sibling bond.

Melissa represents the family of the removed child class.

Karen speaks candidly about her experience with the child welfare system, her life, her struggle, and her healing journey.

She was named Erin Faye Kahnapace, born in Regina in 1979.

She was apprehended twice, once at age three and again at age 11.

“It made life very, very hard for me and my family. My family suffered a lot having me and my sister taken away. We were both adopted out,” she says.

“I grew up not knowing any of my family and not understanding that I was Native. I had a very hard life, very lonely, and I always felt like I didn’t belong. It’s really followed me up until – well, even today – age 41.

Today, she’s “just starting to come to terms with it.”

Watch: National Chief Perry Bellegarde on why AFN filed this suit

But today she’s also a lawyer with a degree from University of British Columbia Law School and a drive to advocate on behalf of her people.

“I know a lot of our people are suffering,” she says.

“There’s a crisis on the ground with our people right now, and, like I said, being at this age and also being a lawyer, I also felt like it was my duty to step up, because I’ve dealt with a lot of trauma.”

When she was re-apprehended at age 11, she started running away from foster care.

“I didn’t know at that age that I was searching for our people, but I was. I just had to be around Native people. I didn’t grow up around Native people except for my brother and maybe two friends at school,” she recalls.

“I was on the street. I ran away. I lived on the street. I was with street people. You have to imagine that, being age 11 – a young girl – especially in Saskatchewan, it’s a very racist province to grow up in. I’m a target all the time.”

She struggled with addiction and violence from age 11 to 20. But things turned around when she moved to Vancouver.

Karen reconnected with family, culture, people, got an education, became involved with ceremony, and stopped using harmful substances.

She describes that time in her life as “12 amazing years,” and has a powerful message for those who are suffering.

“You’re loved. You’re not alone. There’s a lot of us out here that are experiencing the same thing.”

Untangling court cases

Along with Ashley, Karen, and Melissa the AFN is a plaintiff too.

AFN is a “trustee” on behalf of the class, and has a mandate to pursue this litigation from a 2018 special resolution, according to the statement claim.

“Canada breached its responsibility to our children and families, infringed on their Charter rights, and caused them real harm and suffering. We will always stand up for our children,” reads a statement by National Chief Perry Bellegarde.

Andrew Eckart, staff lawyer at the Class Action Clinic at the University of Windsor, tells APTN that it’s usually victims, not organizations, that file class-actions.

A judge will decide whether AFN’s status as plaintiff holds legal water, he says.

Eckart explains that it’s common for multiple statements of claim to be filed on the same issue. The government is already facing another class-action for this with Xavier Moushoom and Jeremy Meawasige as plaintiffs. It’s pending certification.

The Moushoom and Meawasige case was filed in the spring of 2019, and is very similar to the new one. It seeks $6 billion in damages.

Something called a “carriage motion” happens next.

“The court has to decide which one of these firms or plaintiffs – which one of these actions will go forward, while the other one is stayed and doesn’t go forward.”

“The idea is that, if there are two competing firms or two competing groups of firms who say they want to pursue their action, and the other one gets stayed.”

But the firms can also make a deal and combine forces.

APTN asked David Sterns, whose firm of Sotos Class Actions is handling the Moushoom case, about it.

He says his firm became aware last week of the new suit. He confirmed talks are happening, but wouldn’t say if they are planning on combining.

“Our intention, as it has been from the beginning, is to proceed swiftly to trial or, alternatively, to resolution in the best interests of the class which consists of children and young adults who have been the victims of discrimination by the federal government,” says Sterns in an email.

“We have made significant progress in the Moushoom case so far. We are hoping to engage in productive and timely discussions with the AFN with a view to moving forward in the best interest of all of the victims.”

APTN asked Indigenous Services minister Marc Miller multiple times about this. He confirms talks are ongoing.

However, his office has been tight-lipped about those discussions, citing confidentiality.

“We face three decisions, and it’s difficult from our position. Again, it’s not insurmountable, but we face a challenge of having to look at those three different court cases and try to approach it in an equal fashion. That isn’t without some challenges.”

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

The third “decision” which Miller mentions is a 2016 ruling by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) that Canada willfully and recklessly discriminated against First Nation kids on reserves and in the Yukon by underfunding child welfare services.

The tribunal awarded maximum compensation of $40,000 to each victim and certain family members who also suffered.

Both the tribunal and the class-actions only deal with First Nations people on reserves. Non-status, Métis and Inuit are not included.

In 2007, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the AFN brought forward the human rights complaint that eventually became the CHRT ruling.

Cindy Blackstock of the Caring Society emphasizes the tribunal ruling is separate from any class-actions.

“What the tribunal has ordered are human rights damages. A class-action would go above and beyond that, but it is not a replacement for human rights damages.”

“The Canadian Human Rights Act was structured in such a way as to award human rights damages without in any way inhibiting the right of those same individuals to pursue civil action to allow for the exact type of justice the Caring Society is asking for,” she says.

She says the Caring Society wants to support those individuals – like Karen, Ashley, and Melissa – courageous enough to come forward.

Eckart agrees. He says lawyers on both sides need to learn from past settlements like those for the ‘60s Scoop and Indian Residential Schools. Neither, he says, went off without problems.

“The government and the plaintiff’s lawyers have to put their minds to how this class member is going to be adequately compensated, and what the process is and that it’s a fair one to them.”

He says he thinks the new class-action has a good case.

“With the CHRT ruling, I think it was a pretty strong one. There’s been some recognition by the government that what they did was wrong. So, I think that it’s likely there could be a settlement here,” says Eckart.

For Blackstock, however, the injustice is not in the past.

“I want to the end the discrimination that the tribunal has recognized is still ongoing,” she says.