Cullen Crozier

APTN Investigates

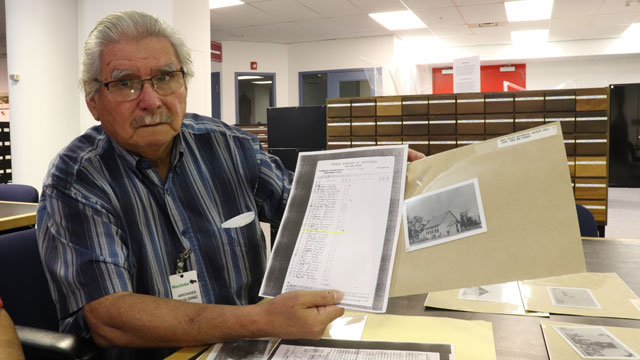

Abraham Parenteau lays out a stack of letters detailing the abuses he witnessed and suffered at a church run day school in the small community of Duck Bay, Manitoba.

The letters are all addressed to top officials in Ottawa including Governor General Julie Payette, Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

The Duck Bay Special School number 2163 is one of more than 680 institutions that were excluded from the recent $1.4 billion dollar Indian Day School settlement.

(The Duck Bay Special School number 2163 circa 1965. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

“It’s like a slap in the face, when I heard that we were not included,” Parenteau says. “That we were not recognized and we were pushed aside. Even though we went through the same process and sometimes ever worse.”

Parenteau and his cousin George Munroe — also a former student of the Duck Bay School, are seeking justice not only the survivors of Duck Bay, but also the other institutions that Canada has so far refused to acknowledge.

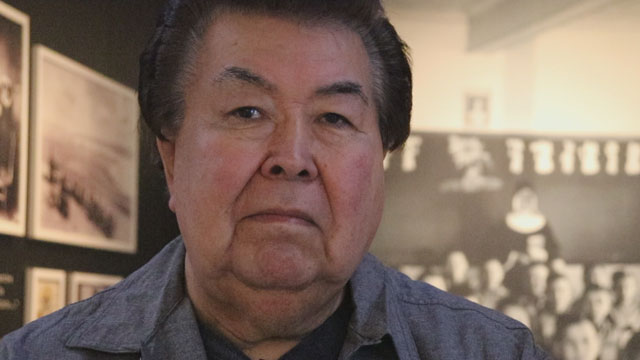

“The church is getting away again,” Munroe says from his home in Winnipeg, Manitoba. “I want a formal class action lawsuit that brings the church, the province, the federal government and the crown under this class action.”

(Former Duck Bay student and Anishnaabe Elder, George Munroe, at the Archives of Manitoba. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

The Indian Day School settlement was approved by the Federal Court in August of 2019.

Up to 140, 000 former students are eligible for compensation with more than 700 institutions officially recognized.

As for the more than 680 institutions that were excluded, Ottawa argues that they provided no funding and had no hand in the day to day operation, usually shifting the blame onto provincial governments or with Duck Bay — a church organization.

“They knew. They were fully responsible,” Parenteau says. “They are fully responsible to rectify this matter and include everybody in a blanket situation and compensate all of these people that were left out from that package. Then everything will be okay.”

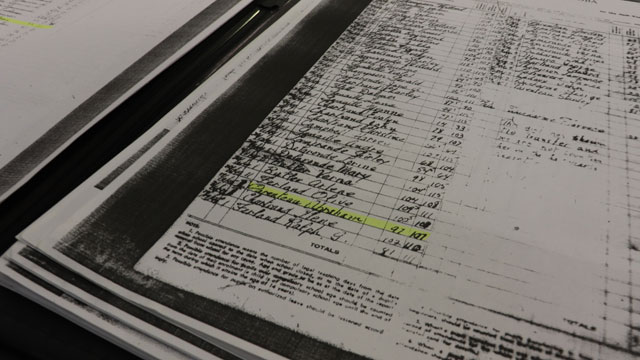

(Abraham Parenteau’s name highlighted on an old attendance record for the Duck Bay School. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

The Duck Bay School was run by the Roman Catholic Church and the allegations of physical and sexual abuse that took place there are horrific.

APTN Investigates spoke with a handful of survivors who all shared similar experiences.

Former students like Stanley Parenteau.

“The things that happened inside that school was too much roughness from the sisters,” says former Duck Bay student, Stanley Parenteau. “They used to kick us around, slap us around, they used to drag us around so we wouldn’t get away.”

Parenteau is in failing health and wanted to share his story while he still had time.

Along with the abuse he suffered, he also recalls being forced to wear a dog leash and collar as a form of punishment.

“Yeah they put a leash on me,” Parenteau recalls. “They used to make sure I don’t run away. Any place where the sisters would go, I’d have to follow because I was like a dog, I might as well say — a dog.

(Former Duck Bay student, Stanley Parenteau. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

While the duck bay school may have been run by the church, given that it operated in an Indigenous community for decades, it’s hard to believe that the federal government didn’t have some form of involvement.

It has become a common defense in these types of cases, and not the first time they have used it.

“They were sent by the federal government,” says former Duck Bay student Abraham Parenteau. “The federal government paid these nuns and these teachers to come to those communities to assimilate. Same thing what they did with the Indian day schools, same thing that they did with the residential schools — they did to us.”

(Former Duck Bay student and Anishnaabe Elder, Abraham Parenteau. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

The exclusion of survivors of the residential school era isn’t anything new.

When the original Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement was approved back in 2005, only 133 institutions were officially recognized.

Since that time, more than 9,000 people have requested that 1,531 other distinct institutions be included — of that number only seven have been added to the agreement.

“There was a lot of parts in motion and it was inevitable, we all knew that there were going to be institutions that were unintentionally excluded,” says Alberta based lawyer Steven Cooper.

Cooper was one of more than a hundred lawyers who helped negotiate the $5 billion dollar Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement in 2005.

(Former prime minister Stephen Harper delivering the 2008 federal apology to residential school survivors.)

“We were not going to get perfection, so we had to get as good as we possible could,” Cooper says. “The risk was to lose the opportunity for anything. So, I think what we achieved in 2005, in a very short period of time, was better than good, but certainly didn’t meet the standard of perfect.”

Cooper is no stranger to the exclusion of survivors from the Residential School Settlement, or the lengths the federal government is willing to go to deny responsibility. He represented the students of Newfoundland and Labrador in their 10 year battle for recognition.

Today his law firm, Cooper Regel is also assisting former students of Kivalliq Hall with their common experience payments and compensation.

Approximately 225 students lived at Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut between 1985 and 1997. The school was the most recent institution to be added to the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement.

In that case, as with many others, Ottawa argued that the school was the responsibility of the territorial government and not Canada’s. The courts disagreed and Kivalliq Hall was officially recognized as a residential school in 2018.

(Kivalliq Hall, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut)

“The federal government constitutionally and historically was or should have been involved in every institution for which the population was primarily and purposely Indigenous,” says Cooper. “And it’s still an argument that we will make and other institutions, I expect in the future.”

But for institutions like the Duck Bay School, proving federal involvement has become a point of contention. Even with the government’s so called push for reconciliation, Ottawa still has a nasty track record of fighting cases like these to the bitter end.

“The government is wrong, when you do injustice,” says former residential school student and advocate, Ray Mason. “And they have a fiduciary obligation to make it right.”

Ray Mason has spent decades fighting on behalf of survivors of the residential school era. He helped launch both the residential school and Indian day school class actions against the federal government.

“They had a fiduciary obligation to look after our safety and wellbeing in those institutions that they put us in,” Mason says. “And they lacked that. They didn’t live up to that obligation.”

Mason rejects the government’s decision to exclude more than 680 institutions from the day school settlement. He says that, regardless of who operated the institutions, at the end of the day, it was the federal government who was ultimately responsible.

And with more and more survivors passing away each year, time is of the essence.

Along with both George Munroe and Abraham Parenteau, Mason has already started reaching out to top officials in Ottawa. He wants one deal, one agreement that will cover all of the institutions that are still fighting for recognition.

“I would like to work out one blanket agreement, not to go to court for each one of them,” Mason says. “Because the courts are very costly, they’re very time consuming and the thing is, we’re passing on by the thousands each year and that’s not fair.”

(Residential School Survivor and advocate, Ray Mason, at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo: Josh Grummett/APTN)

The decision to leave nearly half of the institutions out of the agreement was done behind closed doors.

The settlement is being administered solely by Gowling WLG. The Ottawa-based law firm, was essentially given a monopoly over the settlement by the federal government and stands to receive $55 million in legal fees.

“They make a private deal with the government for 700 schools and the government accepts it because they’re getting off easy,” says former Duck Bay student, George Munroe. “They’re paying half or maybe even a third of what the total cost should be. So naturally the government, save money, we recognize them. But how can you recognize them when it’s only half?”

Gowling wouldn’t sit down with APTN for an interview, but in an e-mailed statement they said:

“We recognize that there are concerns from certain individuals who are not included in the settlement. Significant research went into determining the final list, which only includes schools that were funded, managed and controlled by Canada during specified periods. We cannot speak to the ultimate decision not to include any specific school as those determinations were made by the government.” – Gowling WLG

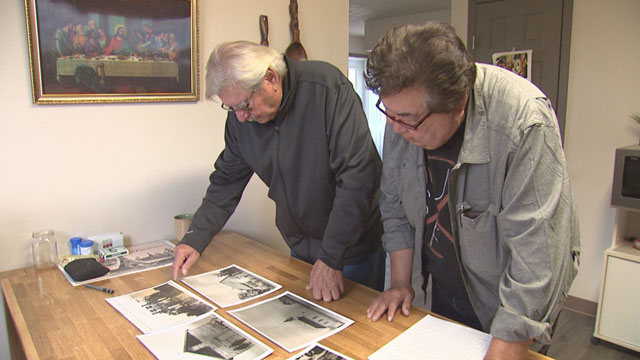

(Anishnaabe Elders, Abraham Parenteau and George Munroe at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

For now Mason, Parenteau and Munroe will continue their battle for recognition. If talks with the federal government fail – they are planning on launching their own class action, not only for the survivors of duck bay, but also the other institutions that Canada has so far refused to acknowledge.

“You’ll never have reconciliation in Canada until you deal with us, you satisfy us,” Mason says. “And then we’ll tell you if it’s done. Nobody has that right to say, well it’s over.”

@cullencrozier

i sure don t have good memories goin to school in Duck Bay, being taken from my home and taken to another residential school in Laurier ,Man, by the priest and nuns

For far to many years the government has only given lip service to not only my First Nations peoples but also to mainstream Canadians. Both sides are tired of it, I know because I grew up in a white community as I am a sixties scoop survivor. I’m told I’m to white to rejoin my community but yet for the color of my skin I was to native for the white community.

With a few years of counseling behind me I have come to realize that I belong to no one but myself. I could be the greatest mediator if I were utilized correctly. Furthermore I have decided that my people need our own political party, so I’ve started the Indigenous Party of Canada. First and foremost I would get rid of all the treaties and revamp Medicare so that all Canadians get access to it. And yes, I’d tax the rich.