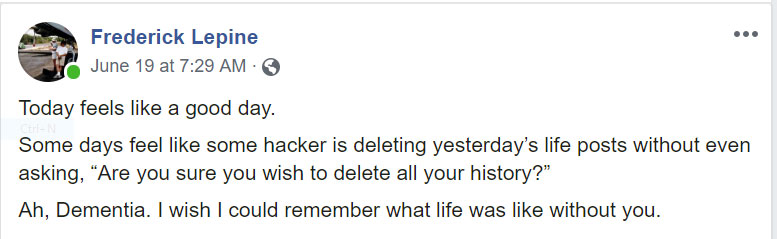

When Fred Lepine felt like he was being tuned out, he plugged in via social media and wrote about his everyday experiences living with early onset dementia.

“This shouldn’t happen to me until I’m in my 70s or 80s but it is happening more and more. I just want people to know its okay to talk about this and we need to otherwise it gets hidden away,” Lepine said.

The 60-year-old from Hay River, Northwest Territories sat down with APTN News by the edge of a lake – a place that helps his memory.

“A colour, a person, a place, a feeling, you name it. I say ‘oh I’ve been there’ and it triggers memories,” he said.

In 2015 Lepine scored 23 out of 30 in a memory test.

The passing grade was 26.

“On July 20th 1969, I sat in this very spot with my mother. I was with my cousins and my brothers and sisters, we were all little kids. I came out of the water and my mother was sitting on a log, she had the radio playing. It was the landing on the moon.

“I have this memory, but still I don’t know what I had for breakfast, or if I even had breakfast,” Lepine said.

(Lepine as a child with his mother. Photo courtesy: Fred Lepine)

These are the kinds of memories that he has started writing down to remind him of where he has been and what he has done.

“I look for a word and it’s not there. I know the sound and shape of the word, I know the spelling but the word just evades me,” he said.

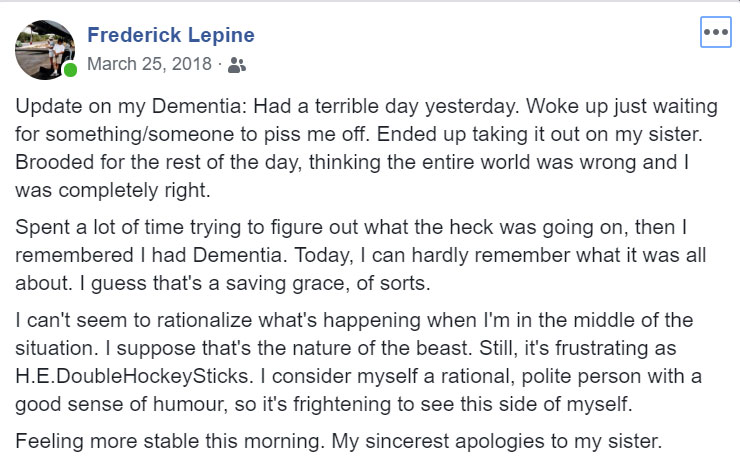

Lepine admitted that he has snapped at his roommate, his sister, but was unable to recall why.

“I wanted to get this out there while I still can. I can see why people say people with dementia get so angry. I can see a side of it where frustration of not being able to express yourself all the time or in the way they want.

People end up isolating themselves,” Lepine said.

The once respected air attack officer battled forest fires for 18 years.

He earned the name “Fearless Fred” and often completed dangerous tasks that others turned down.

Now Lepine said he’s experienced medical professionals putting disease before personality.

“I went to an eye doctor in Edmonton, I was laughing and joking with them. I told them I had dementia, so anything they told me to tell my sister, patient escort.

“They immediately shut up and stopped laughing because they didn’t know how to deal with this,” he said.

(Lepine, front centre, with his fire fighting crew in the NWT. Photo courtesy: Fred Lepine)

Martha MacLellan, head of the regional Alzheimer Society of NWT and Northern Alberta located in Yellowknife agreed that dementia-specific training is one of many ways patient care can be improved.

In her opinion, the stigma surrounding dementia contributes to late diagnoses.

“When a doctor comes in and someone examines them they don’t do follow up. If they (doctors) could refer them to me as soon as they make the diagnosis it makes it a lot easier to offer supports early on, instead of waiting till the family is in crisis,” MacLellan said.

Misconceptions around dementia and aging can also lead to late diagnoses.

“One of the things that most people will say when someone says ‘I am worried, I keep forgetting things, maybe I should go in and get checked,’ they say ‘oh everyone forgets as they get old.’ That person is probably frightened and wants to talk about it but as a society we just brush it off a lot of the times,” MacLellan said.

The Society has an initial meeting with the family and then heck back every six months to see how they are progressing and what support they need during these different stages.

From then on we do yearly check ins unless we find out they need more frequent supports.

Families who have reached a crisis point make up the majority of her clients.

According to MacLellan, support for caregivers is equally as important as the support for loved ones living with dementia.

“Caregiving for someone with dementia can be very isolating and it is really good to have someone to sit there. listen and just to let them know they are doing a good job,” she said.

Last year she ran a pilot project for a community ambassador program.

(Lepine at the piano in an undated photo. Photo courtesy: Fred Lepine)

Two volunteers located in Inuvik, Fort Smith, Hay River and Behchoko learned how to be a liaison between MacLellan and the families to provide support.

In October 2019, the society is looking at bringing the training to two new communities, Fort Simpson and Norman Wells.

Making the effort to reach out to friends and family when living with dementia is something Lepine has to actively work at every day.

“I feel like I’m living in a bubble. Outside is everyone else’s world and inside is mine. Sometimes it gets bigger and I include other people and event but for the most part it gets smaller,” he said.

Ending the interview Lepine stressed one final point – that he is still here, and he is still himself. With that he smiled and looked out over the lake.