Brielle Morgan, Francesca Fionda, Samantha Garvey, Brittany Hobson, Jon von Ofenheim

The Discourse, APTN News

The ministry responsible for some of B.C.’s most vulnerable kids is failing to meet basic requirements for their care — according to government records.

The Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) is the de facto parent for about 6,500 kids in foster care in B.C., but if ministry audits are any indication, the safety and well-being of these kids is in jeopardy.

From 2014 to 2018, the ministry gave itself a failing grade on more than 40 per cent of its critical performance measures, our investigation reveals.

The Discourse pulled data from 37 audits which measured the performance of social worker teams across B.C. for a five-year period.

The data shows that social workers aren’t assessing potentially urgent calls for protection quickly enough, completing safety assessments on time, or monitoring the well-being of kids placed in foster homes and adoptive homes.

“It’s shocking,” says University of Victoria social work professor Susan Strega. “I look at the data and it’s crystal clear. People are routinely out of compliance with really important policy directives and standards.”

This “should be a four-alarm fire,” she says.

A close look at some ‘critical measures’

When a call comes in about a potential case of abuse or neglect, child-protection workers need to act fast to assess any potential danger. It’s their job to determine whether they need to visit the family within 24 hours or five days.

For Strega, this is one of the most important responsibilities a social worker holds.

“Absolutely the most critical thing about all these, I think, is assessing whether or not children or youth need protection,” she says.

“That is the most important because that’s the core business of child welfare.”

The Discourse asked Strega and other experienced social workers, instructors and people who held senior leadership positions at MCFD to look at the ministry data we compiled by region, year, practice and compliance level, and point out some of the most important tasks measured.

Explore the data

The Discourse made the data that was compiled from the audits available online. You can explore the data here and let us know what you think.

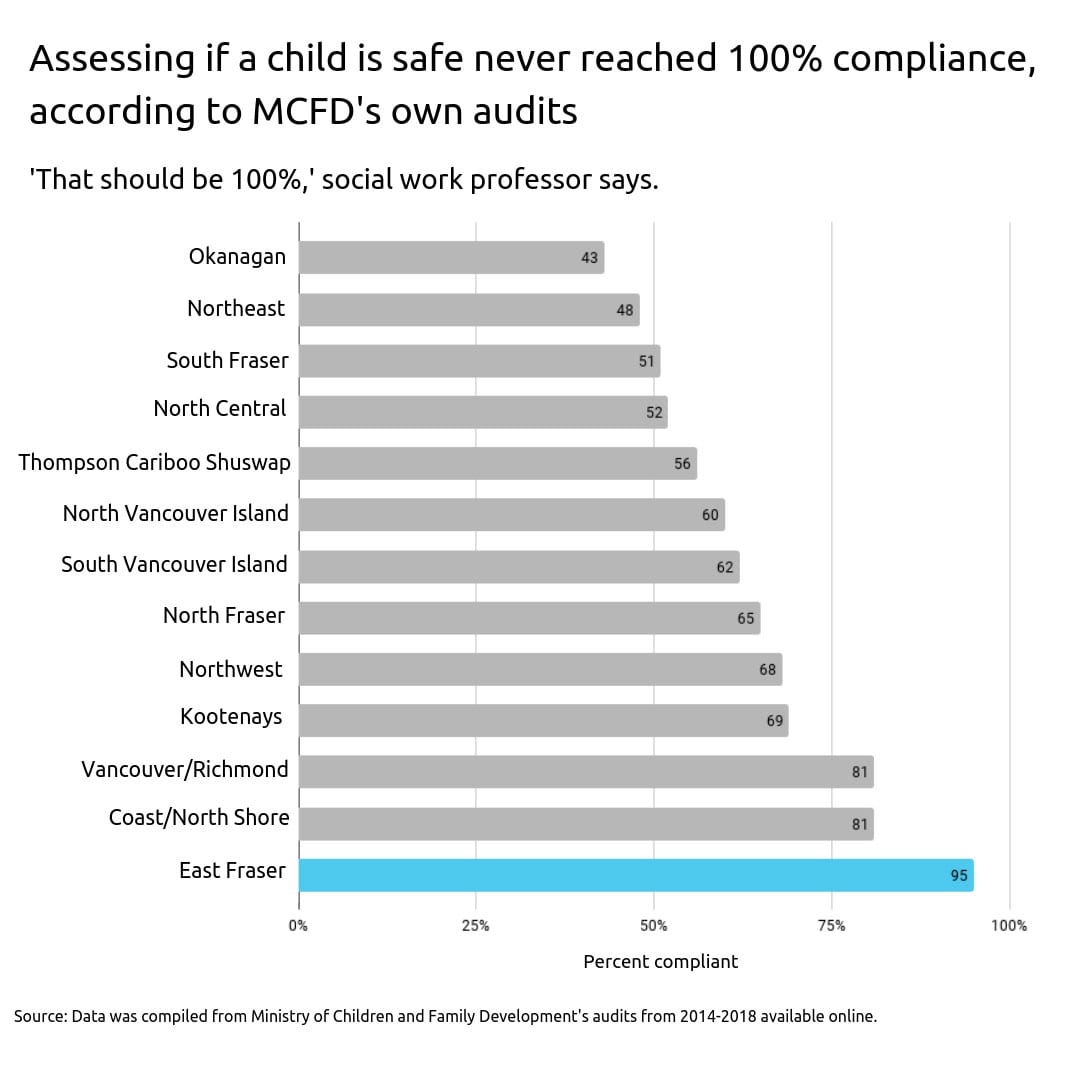

According to the ministry’s data, none of the social worker teams audited between 2014 and 2018 in B.C. were 100 per cent compliant on promptly assessing initial reports of potential danger.

Though most of the teams achieved 50 per cent or higher — and the North Fraser district scored 98 per cent in 2016 — Strega says anything short of full compliance on this measure isn’t good enough.

“Ninety-eight per cent is really, really good — [but] we want to see 100 per cent compliance,” she says.

Strega would also like to see 100 per cent compliance on safety assessments.

Social workers are supposed to complete these assessments during their first “significant” visit with a family, according to MCFD’s child-protection policies. The purpose of these assessments is to figure out if the child is in immediate danger and what kind of help the family needs, if any.

These assessments are a “really big deal because those go directly to the safety of the child,” says Margo Nelson, a social work instructor at Langara College. “If that’s done badly that’s the kind of thing where crisis happens.”

In B.C., no regions achieved 100 per cent compliance for this measure. The highest was East Fraser at 95 per cent in 2016.

“That should be 100 per cent,” says Strega. “I’m mystified as to why it would be lower than that.”

It’s not simply at the early stages of a family’s involvement with the child-welfare system that the ministry’s failing to meet its own standards.

Non-compliance runs deep — following children as they’re moved through the system into foster homes or placed with prospective adoptive parents.

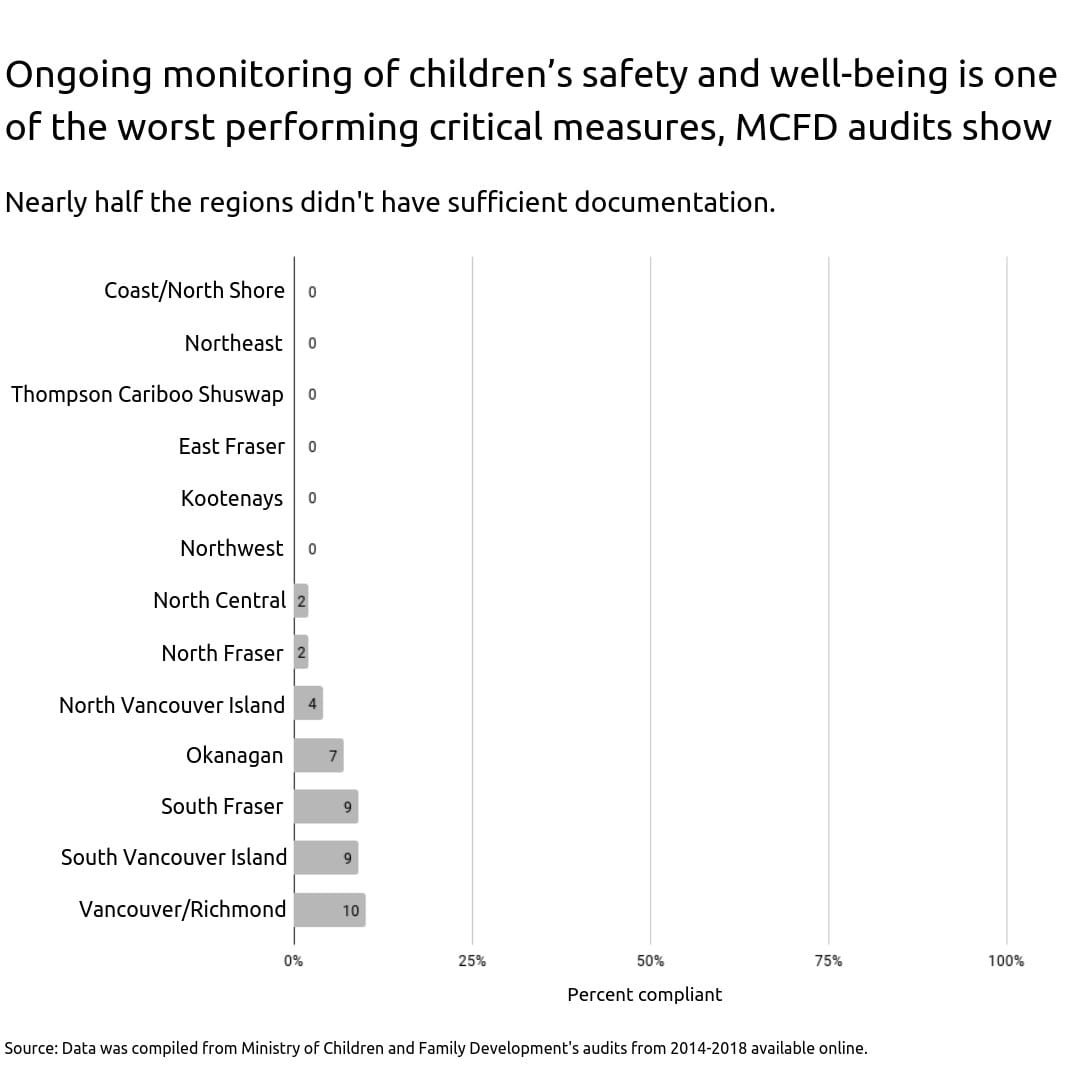

When a child is in care, social workers are supposed to check in with them regularly to make sure they’re safe and well. According to MCFD’s policies, social workers are to make “in-person, private contact with the child or youth at least once every 90 days.”

In nearly half of the regions audited, there was zero documentation showing ongoing monitoring of children in care.

“Sometimes, when things sort of seem settled, it becomes very easy for that child’s visits and things to drop — and that speaks to social workers’ capacities and caseloads,” Nelson says. “If that slips, that’s when things happen.”

“Caseloads are absurd,” she adds. “There’s too much to do to actually get it done.”

(“Assessments are a really big deal because those go directly to the safety of the child,” says Margo Nelson, a social work instructor at Langara College.)

Chronic understaffing, resulting in stress and burnout of social workers, has been well documented in B.C. In October 2015, then-Representative for Children and Youth Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond released Thin Front Line, an in-depth look into staffing issues in B.C.’s child-welfare system.

She found that even fully-staffed MCFD offices found it impossible to keep up with workloads.

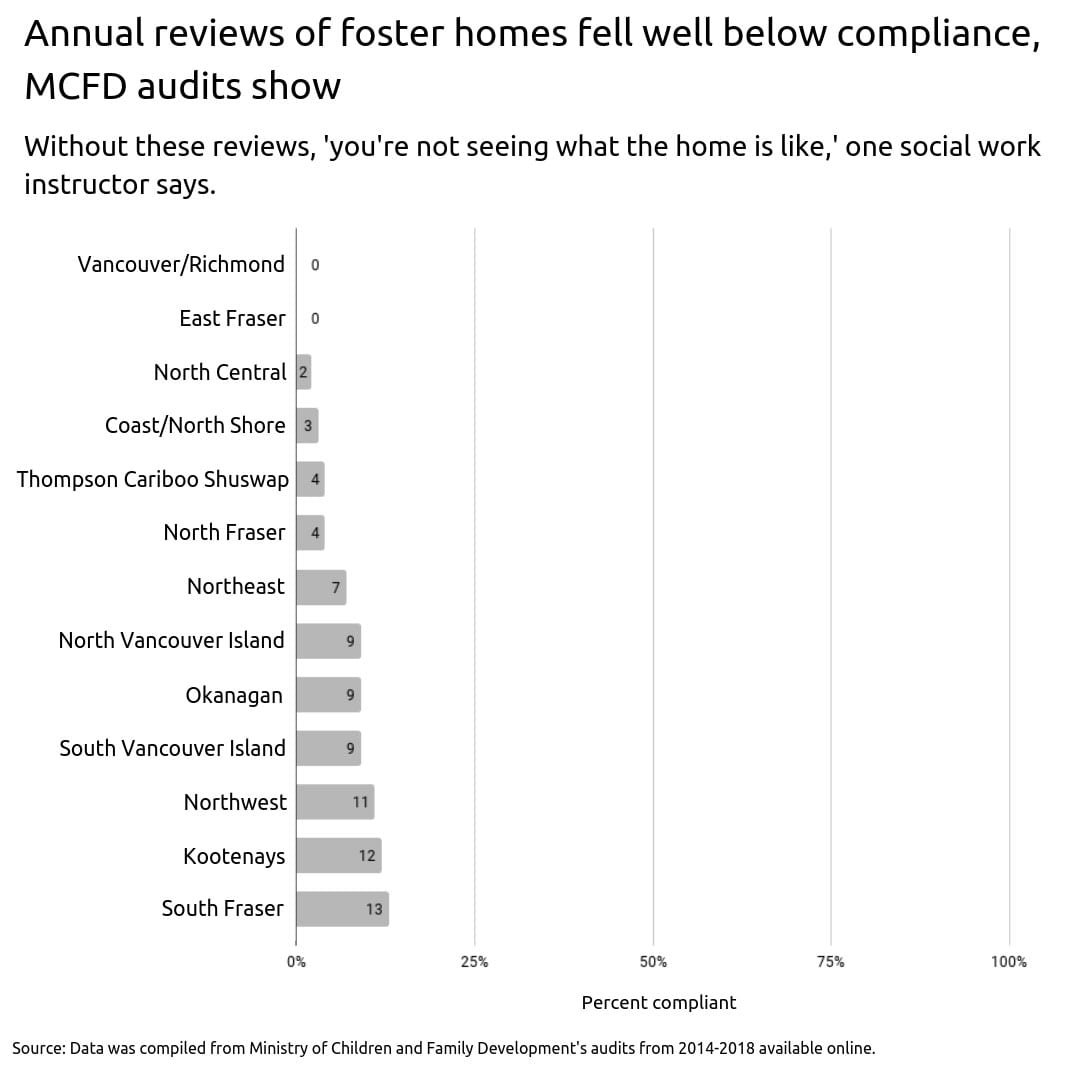

Not only are social workers failing to visit youth in care on a regular basis, the audit data also shows they’re not completing annual reviews of foster homes. These reviews are supposed to be completed within 30 days of the anniversary date of a child’s placement, but in many cases no reviews were done in the 36-month period leading up to the audit.

“If you’re not having annual reviews of what’s going on, that means you’re not talking to the kids alone, you’re not seeing what the home environment is like,” Nelson says.

Social workers are likewise supposed to check in regularly with kids who’ve been placed in prospective adoptive families.

The period after a child is placed in an adoptive home is the most “tension-filled time in their life,” says Anne Clayton, who was the ministry’s director of adoption when she retired in 2016.

It’s the social worker’s job to help the family understand the child’s needs and the community services available to them.

“If we put a special needs child in your home and then walk away and leave you to figure it out by yourself, the odds are that placement’s going to break down,” Clayton says.

According to the audit data, the compliance rate for “post-placement responsibilities” never reached 100 per cent in any regions. The highest was North Vancouver Island in 2017 with 48 per cent.

What’s the ministry doing about these low scores?

Anne Clayton, the former MCFD director who retired in 2016, says she isn’t clear on how the ministry holds itself accountable for poor audit results.

“From my own experience, I don’t think much happens with the audit data,” she says.

While the ministry only started auditing compliance in adoption cases shortly before she left, Clayton spent 22 years working for MCFD in positions that ranged from frontline to head office, and the ministry’s been using audits for decades, despite variations in form and frequency.

“The auditors go out and do their thing, they meet with the team leader and the leadership of the [Service Delivery Area], and they come up with some recommendations. It’s more like it’s a perfunctory ‘you have to’ — and they move on.”

Audits “could be a wealth of information that should be telling leadership a whole lot of things,” she says, but that doesn’t seem to be the case.

For over two decades, inquiries, reviews and reports have recommended that the ministry improve its auditing practices by making audits more comprehensive, looking at the data as a whole and finding ways to ensure audits resonate with social workers in the field.

But according to a 2013 report from the Representative for Children and Youth, the team in charge of improving audits has “suffered periods of inattention and inactivity resulting in a rupture in accountability.”

Is there a better way to measure performance?

The thing about audits is they capture “only what’s documented,” says one social worker in the Lower Mainland.

KB, who asked that her identity be protected for fear of losing her job, says social workers are managing one crisis after another and often don’t have time to complete their paperwork within the legally mandated timelines.

Social workers are “running around like chickens with our heads cut off,” says KB. “It’s not that people are lazy, generally, or just don’t feel like doing it, or think they can cut corners. It’s not definitely that. They just don’t have time to do it… You’re trying to document everything but you can’t.”

KB says she’s currently juggling 30 cases, and she’ll always prioritize a child’s immediate safety over filling out forms — even if that means low compliance scores on the audits.

“At the end of the day, when there’s a child-protection concern that comes in, would the public rather that we’re going out to investigate it, or sitting and filling out a form?”

This question gets at the heart of the problem with the ministry’s audits, according to Doug Magnuson. He’s an assistant professor at the University of Victoria’s School of Child and Youth Care, and he specializes in qualitative and quantitative methods for evaluating and interpreting practice.

“One of the things we don’t know about is the connection between the amount of paperwork completed and quality of the work,” he says. Without knowing this it’s hard to say how accurate and valuable the audits are.

Chuck Eamer cautions against taking the audits at face value. During his 28 years with the ministry, he worked on the frontlines as a social worker, managed regional teams, and served as an assistant deputy minister where he shared

Responsibility for quality assurance. Since retiring from government in 2012, he’s worked as a consultant.

While it’s important that standards are externally monitored because “the powers of the child protection system are some of the most onerous in government,” he says, there’s only so much we can learn from these audits.

“These measures are an attempt to sort of do a biopsy and take a slice and do an analysis,” Eamer says. “In some ways, they’re a better window than none, but they’re just a window into the world of child welfare.”

Magnuson thinks MCFD could develop better ways to measure performance. For example, he says, the ministry could ask children in care to evaluate the care they are receiving.

“Data could be collected directly from clients — from youth in care, from youth in temporary care — about how well they’re doing,” he says. “They aren’t doing that.”

He points to Wisconsin as a model for both evaluating child-welfare systems and data transparency. The state regularly publishes a wealth of comprehensive data on its website.

“Their measures are very simple, but also quite powerful,” he says. “B.C. could be doing the same thing.”

The bottom line is B.C. needs to do something about social workers’ inability to meet standards, says Anne Clayton.

The audit data has her brimming with questions: “Are there enough social workers? Are there enough resources? … What is the leadership of the director of child welfare? Where is society in all of this?”

When children are removed from their parents’ care and placed in publicly-funded government care, we’re all accountable, Clayton insists.

“There’s no way the ministry can do this all by themselves as social workers. It’s a societal responsibility,” she says, “and much as we want to ignore all of our problems, we’re all at some level of responsibility for these kids.”

This story was produced as part of Spotlight: Child Welfare — a collaborative journalism project that aims to deepen reporting on B.C.’s child-welfare system. It story was originally published by The Discourse. Tell us what you think about the story.