A plaintiff in the Indian day school class-action lawsuit is worried survivors are dying off while a consortium challenges the settlement agreement proposed by Gowling WLG of Ottawa.

“They’re going to try and stall it,” Ray Mason said of the consortium comprised of lawyers and Indigenous organizations.

“Meanwhile, there’s hundreds of survivors passing on each day.

The consortium is comprised of Indigenous organizations and independent lawyers like Joan Jack, an associate lawyer with Alghoul & Associates of Winnipeg.

Jack first represented Mason and lead plaintiff Garry Mclean in their original $15-million class-action against Canada before being replaced by Gowling.

Mason said he and McLean, who died in February, credit Jack for getting the ball rolling on the class-action in 2009.

She travelled the country collecting names of former students for a database to form the proposed class.

“I don’t think we’d be sitting here talking about it today if it wasn’t for her and I,” Mason said.

But then things turned sour.

“Her and Louay Alghoul were not doing any work on it for three and a half years or more,” Mason said. “We wanted to move on.”

McLean suggested the same thing in an affidavit he swore on May 2018 that was filed in Federal Court.

He said the class-action “lay dormant for six years. Out of frustration with the delay despite repeated requests for movement on the case, we met with and subsequently retained Gowling in May 2016.”

Garry McLean was lead plaintiff in the Indian day school settlement agreement. He died in February 2019 at the age of 67. (Submitted)

But Mason said the pair refused to turn over the database with more than 5,000 names, prompting Gowling to remind them they were no longer representing the class and “bound by the Code of Professional Conduct” as previous counsel.

“Ms. Jack and Mr. Alghoul are actively withholding evidence from Mr. McLean and Mr. Mason,” Gowling partner Robert Winogron said in a letter to the pair obtained by APTN News, “evidence that was gathered in the course of this litigation.

“Previous counsel may not keep evidence garnered in the context of Mr. Mason and Mr. McLean’s litigation from their present solicitors of record.”

There was no response from Jack and Alghoul to the letter or affidavit.

Mason said he and McLean also lodged a complaint against Jack and Alghoul with the Law Society of Manitoba.

A complaint the Society confirmed remains “under investigation.”

Mason, a member of Peguis First Nation, said the database was eventually returned – “but not without a lot of unfriendly words.”

“I’m an Elder and I honour what she did. But now I question her actions,” he said.

The consortium wants changes to the agreement-in-principle announced by Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett on December 5.

One of the changes they want is adjudicated hearings similar to the Independent Assessment Process (IAP) under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

They say many survivors benefitted from disclosing their experiences in the private hearings used to determine the level of sexual and physical abuse and subsequent compensation.

But Mason, who spent two years in a day school before being ordered into a residential school, and other plaintiffs strongly disagree.

“Some people can’t handle that,” he said. “To re-live all the trauma that we went through.

“This IAP, it takes too long, it’s not user-friendly. And you’re on edge right from Day 1 until they make you an offer and you make that decision whether you want it or not.”

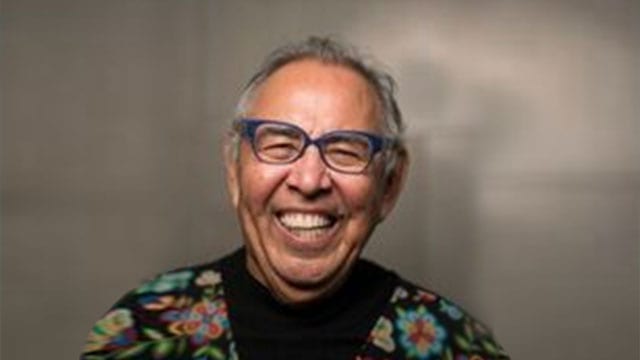

Lawyer Joan Jack filed the first Indian day school class-action lawsuit in 2009. (APTN file)

Lawyer Joan Jack filed the first Indian day school class-action lawsuit in 2009. (APTN file)

Still, Jack supports changes to the agreement.

“There’s lots of problems with the agreement, and so we want to improve (it) for people,” she said, noting the judge can order Gowling and Canada to meet with the intervenors and reach a new agreement within 30 days.

“It wouldn’t delay anything – it would just make it better.”

She said several Indigenous organizations are on board.

“Matthew Coon Come, (Grand Chief of) the Grand Council of the Crees, sought intervenor status, Bobby Cameron (chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations) sought intervenor status, the Inuit sought intervenor status,” she told APTN in a telephone interview.

“There are eight individuals and/or organizations are seeking intervenor status because they want to tell the court information they believe the court needs to hear.”

The multi-million agreement includes funds for legal fees, a legacy fund, and individual compensation of between $10,000 and $200,000.

The agreement still has to be certified by a judge, with a hearing scheduled in Winnipeg Federal Court next month.

See the registration form here.

In his May 2018 affidavit, McLean said the settlement was endorsed by “several prominent First Nation organizations,” and he’d been working since 2006 to get recognition for day school survivors not included or compensated in the Indian Residential Schools settlement.

Approximately 200,000 Indigenous students were legally forced to attend more than 700 government-funded day schools legislated by the Indian Act, beginning in the 1920s.

Gowling estimates there are 150,000 remaining day school survivors dying at a rate of about 2,000 per year.