Enbridge Inc. says its natural gas pipeline in B.C., which exploded last fall in Lheidli T’enne traditional and unceded territory, must continue to operate because it would impact millions of people in and outside the province.

“It is not in the public interest to stop operating a critical piece of energy infrastructure that millions of people in B.C. and the U.S. Pacific Northwest rely on every day,” the company says in a statement posted on its website.

The explosion took place on Oct. 9, 2018 near Prince George.

Last month the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation filed a lawsuit against Enbridge in B.C. Supreme Court.

They have requested a permanent injunction that would prevent the company from operating the pipeline in their territory and reserves. They also ask for the pipeline’s immediate dismantling and removal.

In a phone interview with APTN News, elected Chief Dominic Frederick said, “We are worried about the safety of our community and our members.”

“That pipeline could explode again, here or in someone else’s backyard, and we don’t know why.”

Frederick says the company has not offered his people an explanation for the explosion, or an apology.

“No one is safe until we know the cause of the explosion,” he says.

The pipeline rupture blasted a massive fireball into the sky just five metres from the Southwestern corner of the nation’s reserve.

A natural gas pipeline owned by Enbridge Inc. exploded in B.C. last October. Photo: Dhruv Desai/Twitter.

Frederick says the explosion was felt in nearby homes and at the Band office over two kilometres away.

No one was injured, but nearly 100 community members evacuated their homes. They had to cross over the pipeline on their way out.

“In our community there is only one route in and out,” says Frederick. “You don’t have a choice but to go over the pipeline.

“We were very lucky those parts of the lines didn’t explode as well.”

In an email to APTN News, Enbridge explained their pipeline system in B.C. runs 2,858 kilometres and is made up of two lines that run parallel to each other.

They said the line that exploded is a 36-inch pipe that was installed in 1972.

The other, a 30-inch pipe, dates back to 1957.

Both lines were isolated and shut down following the incident.

The smaller pipeline was back online the following day, operating at 80 per cent of its normal capacity.

Almost a month later, following repairs to the ruptured pipeline, Enbridge restored its operations to 80 per cent of its normal capacity.

Frederick says he was appalled the company reopened the line without knowing the cause of the explosion.

“All anyone could talk about was getting the gas back on,” he says. “There was no talk about the safety of our community and members.

“They turned it back on without answers and without our consent. They didn’t care about us.”

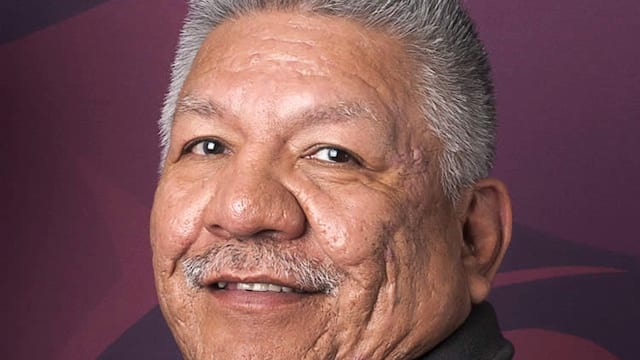

Lheidli T’enne First Nation Chief Dominic Frederick. Photo: www.lheidli.ca.

Although the pipeline is regulated by the National Energy Board (NEB), the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) is leading the post-incident investigation.

The return-to-service plan was reviewed by the NEB and Enbridge conducted a dig to validate the integrity of the entire system.

Both pipelines continue to operate at a reduced capacity until the regulatory review is complete.

In October, an RCMP investigation ruled out criminal activity.

Investigators from TSB have collected and examined the wreckage, but a final report has not been issued.

Malcolm Macpherson, lawyer for the Lheidli T’enneh, says his clients have been totally shut out.

“They received the odd surface-layer email, but they haven’t been participants in the investigation and that is wrong,” he says.

“This pipeline literally blew up in their backyard, yet they are not involved in the investigation, the gas was turned back on without their consultation, without their participation, and very importantly, without their consent.

“They are Section 35 rights holders and they are not being treated that way.”

Macpherson is seeking compensation for damages, nuisance and trespass and a declaration that the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation was never consulted on the construction, operation, repair or return to service of the pipeline.

Lawyer Malcolm Macpherson is representing Lheidli T’enne First Nation in their lawsuit against Enbridge. Photo: Laurie Hamelin/APTN.

He says while there are a number of reasons behind the lawsuit, “first and foremost it’s about human safety.”

“There was also a perception on the part of the Nation that Enbridge was not respecting them and acted as though it was business as usual,” he says, adding “there is now a profound lack of confidence in Enbridge.”

In its public statement Enbridge says it is “committed to fostering a strengthened relationship with Indigenous communities, including the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation, built upon openness, respect and mutual trust.”

The company also says it has “committed a team involving senior executives to negotiate a settlement and an agreement to frame the relationship going forward.”

Despite its issues with Enbridge, the First Nation says it’s still open to working with others in the industry.

The Lheidli T’enneh signed an agreement with Coastal GasLink and say they’re looking forward to construction of the new natural gas pipeline later this year.

“We have nothing against industry, nothing against pipelines,” Frederick says.

“What we don’t want is unsafe transportation of hydro carbons, and it’s important that we stand up for our rights.”