The Trudeau government is moving ahead with its promised Indigenous child welfare legislation.

Federal ministers and national Indigenous leaders gathered at a press conference in Ottawa to celebrate the introduction of Bill C-92, An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, which offers First Nations, Inuit and Metis an opportunity to take over jurisdiction for child and family services.

Leaders said the bill recognizes the inherent right of Indigenous communities to make decisions about their own children.

Under the current system provinces have jurisdiction over child and family services, which has resulted in Indigenous children being taken from their families, communities, land and culture and raised in foster homes run by provincial agencies.

If passed into law, the new legislation would give Indigenous communities an opportunity to work with provinces to take over jurisdiction.

It would also prioritize prevention before apprehension and consider a child’s “cultural, linguistic, religious and spiritual upbringing,” as factor in determining the best interests of the child.

In order to take over jurisdiction of child and family services, Indigenous nations and communities would enter into negotiations with the federal and provincial—or territorial—governments to work out details.

If no agreement is reached after 12 months, and if “reasonable efforts were made to reach an agreement, the laws of the Indigenous group and community would have force of law as federal law and would prevail over federal and provincial laws,” according to a government document circulated to media Thursday.

Indigenous Services Minister Seamus O’Regan said the bill “finally affirms what Indigenous communities across this country have been asking governments to recognize for decades, that Indigenous communities have inherent jurisdiction over child and family services, and that they should be the ones deciding what is best for their children and for their families.”

Former Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott said C-92 “is going to change people’s lives.”

Last November Philpott announced Canada and Indigenous leaders would co-develop the legislation, and that the bill would result in the end of an era of “scooping children.”

Canada and provincial governments’ laws related to child welfare have been compared to the residential school system and the Sixties Scoop.

Indigenous children account for more than 52 per cent of all children in state care in Canada, but only comprise about eight per cent of all children in the country under 15.

In Manitoba alone, roughly 10,000 of the 11,000 children in state care are Indigenous.

O’Regan said the legislation “means that the Inuit can be in the driver’s seat. It means that Metis for the first time can be in control of child and family services.”

Metis National Council (MNC) President Clement Chartier said Thursday he’s happy with the bill, but that implementation “could prove to be a challenge,” with jurisdiction matters with the provinces yet to be resolved.

“But the desire is there,” he said.

Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, said while the bills holds promise, some Inuit regional governments “don’t feel as though they’ve been given enough time to fully endorse the bill as it would stand today.

Obed said ITK is “hopeful that over the next month or two if there are concerns with the legislation they can be brought forward, and that Inuit and the government can work on amendments to the legislation as it was put forward.

“That is speculative,” he added. “We’ll just have to work with our leadership across Inuit Nunangat and that the government would then work with us on amendments are necessary.”

Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde praised the legislation, saying “we need to get this right.”

“Getting it right means that it’s not a giving of jurisdiction, but a recognition of jurisdiction…a recognition of the inherent right to self-government, inherent right of self-determination,” he said.

But not all First Nation leaders are excited about the bill.

For weeks some have been speaking out after a draft bill was circulated among a working group of leaders who were helping co-develop the legislation.

They said Philpott had suggested the transfer of full jurisdiction from provinces to First Nations was “doable”.

Grand Chief Arlen Dumas of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs said in a statement Thursday that the bill “does not meet the immediate need in addressing the humanitarian child welfare crisis in Manitoba.

“The promise was to hand over full jurisdiction of child and family well-being directly to our First Nations, period,” he said.

“I’m stating again that we have the right to full jurisdiction over our children and families and we require dedicated CFS funding to First Nations.”

Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO) Grand Chief Garrison Settee voiced cautious optimism about the bill, saying MKO wants to review it “before it receives royal assent so that we have enough time to make sure that our input is reflected in the process.”

Settee, who represents 33 bands in northern Manitoba, said he was relieved the Liberals kept their promise to introduce the bill.

A spokesperson for Manitoba’s Minister of Families says the bill “does appear to reflect work the Manitoba government is already leading to transform the child welfare system,” and that the province “will continue to work with the Indigenous Leadership Council, communities, Child and Family Services (CFS) authorities and the federal government to achieve our shared goal to improve the child welfare system.”

But in neighbouring Saskatchewan, which also has staggering numbers of Indigenous children in care, the governing Saskatchewan Party is challenging the legislation.

Saskatchewan Social Services Minister Paul Merriman told APTN Thursday that his government is already doing many of the things outlined in the new bill.

“Unfortunately, the federal government chose not to collaborate with provinces and territories to develop this legislation,” he said. “Valuable input could have been provided by those across the country who develop child and family services and deliver them every day, including provincial and territorial governments.”

David Pratt, a vice chief with the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) in Saskatchewan, is not surprised at the pushback from the province.

“We have an issue with race in this province,” he said in a telephone interview from Saskatoon. “That’s no secret.”

Pratt praised Philpott, who did the lion’s share of consultation on the bill.

She “had the trust and the support of every region and First Nation across Canada. She took our concerns and actually listened to us in a sincere way,” he said, adding FSIN will review the bill to see if it delivers what they were expecting.

On Wednesday FSIN issued a statement calling for the removal of Section 88 of the Indian Act, which gives provinces jurisdiction over child welfare.

Earlier this month the organization, which represents 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan, said it would not support the bill if it didn’t include the transfer of full jurisdiction from the provinces to First Nations.

Several First Nation leaders have also expressed concern over funding, saying their support for the bill is contingent on sustainable, adequate funding for the transfer of jurisdiction and thereafter.

Cindy Blackstock of the First Nations Caring Society says the bill’s lack of clarity around funding is “really concerning.”

Blackstock, who has led a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) case against the federal government for failing to provide the same services and support for First Nations children as non-Indigenous children, also noted that Jordan’s Principle isn’t mentioned in the legislation.

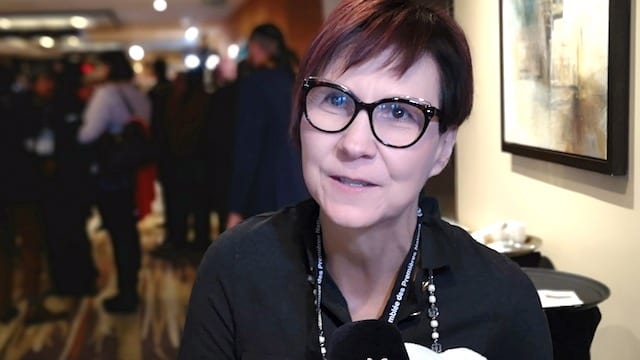

Cindy Blackstock says Bill C-92 must be amended to provide guaranteed and adequate funding. APTN file photo.

“I don’t want to see the hard fought gains that First Nations communities have made at the CHRT not integrated into this important piece of legislation.”

She said there’s still an opportunity through the legislative process to amend the bill in a way that would guarantee adequate funding, but that “it’s a question of political will.

“We’ve already provided language to Canada on how to rectify the funding issues,” she said, adding some First Nations have also suggested language to address funding in any proposed legislation.

Blackstock said any language around funding should “protect the funding principles that are embedded in the CHRT, obliging the federal government to provide funding in keeping with those principles.

“The wording needs to be specific enough that if the federal government does not meet its obligations to First Nations children and their families, that the First Nation could hold Canada legally responsible,” she said. “And there’s nothing in there at this moment.”

The CHRT has said funding for First Nations child welfare should be needs-based, meaning the government funds whatever is necessary to achieve the best outcome for a child.

Blackstock said the best people suited to make those determinations are those on the ground who are working with the child, not federal bureaucrats or politicians.

“That’s why the tribunal has ordered on an interim basis that funding be provided at actual cost, so that it’s not people in Ottawa who haven’t seen the family, haven’t seen the child, and often aren’t trained in this area, who are overriding the views of families and professionals on the ground.”

With files from Kathleen Martens.