A decade-long access to information fight by Amnesty International has uncovered documents the organization says reveal a deep-seated bias in how the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) handled the Mohawks land dispute in 2008.

“From the very beginning we think the response to the land occupation and protests in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory were vastly disproportional to any credible evidence of any threat to public safety,” said Craig Benjamin, who works for the human rights organization.

“Do I really think the OPP are there for public safety? Absolutely not,” said Dan Doreen, a Mohawk land defender, who was on the frontlines of the land reclamation in Tyendinaga.

“Does public safety encompass Indigenous people? Absolutely not.”

Larry Hay is a Mohawk investigator based in Tyendinaga. He worked with Amnesty International to examine the OPP actions.

He said this is still very much a live issue for his community.

“Why is it important ten years on to move this forward? Because these issues have never been addressed,” said Hay.

Hay is a former RCMP officer and former chief of the Tyendinaga Mohawk Police.

“What happened here in 2008, here Tyendinaga at the Culbertson Tract turned out to be an example for police of how not to manage an Indigenous protest,” said Hay.

The Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, in southeastern Ontario, sits on the shores of the Bay of Quinte, framed by Highway 401, the train tracks to the north and two small towns on either side.

In 1995, the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte filed a land claim for a 900 acre (364 hectares) area called the Culbertson Tract. Roughly a third of it is farmland, but it also includes part of the small town of Deseronto, which borders the reserve.

“All the important part of the town is on stolen land,” said Doreen.

The land claim is still under negotiation.

Back in 2007, the Mohawks had already protested a permit granted by the province to a local developer for a quarry in the land claim area.

They occupied the quarry site and shut it down.

That occupation was still going on a year later, when another property developer announced plans for 200 housing units in Deseronto, in another area that’s part of the land claim.

“It was always about the land and it was stopping development of the land,” said Doreen. “And we did that.”

The 2008 protests and police actions largely happened out of the public eye.

But through freedom of information, Amnesty International has accessed documents including officer’s notes, briefing books, police interviews, and footage recorded by the OPP – video never before seen by the public.

“Do you need 200 police officers to address a situation which is at most one of mischief? Or perhaps one where no laws are being broken?” asked Benjamin.

The OPP deployed the Public Order unit, the Canine unit, a helicopter and the Tactics and Rescue Unit (TRU), commonly called the sniper squad or swat team.

He said the initial decision to maintain such a heavy police presence in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory reveals bias and a lack of neutrality.

“You’re sending a message to your own officers that they are not in a situation where they are providing protection to people who are sincerely trying to assert their rights,” said Benjamin.

“But you are dealing with potentially violent individuals who require the highest level of police response.”

Benjamin said the political landscape influenced police actions.

The federal government accepted the land claim in 2003. The Mohawks have always wanted the land returned. But Canada’s policy on settling claims is to offer financial compensation.

And so while negotiations at land claim tables inched forward back in 2007 and 2008, government’s message to land developers was “business as usual.”

That was clear in an OPP audio recording of an interview with property developer Theo Nibourg in April, 2008.

“Government tells us it’s business as usual and we can proceed as we see fit,” Nibourg told an OPP detective 10 days before the blockades began.

“The OPP looked at an arbitrary federal policy which was to refuse to take action to return the land. And the OPP interpreted that as being the law,” said Benjamin.

“To say it was ‘business as usual’ only perpetuated the myth that nothing was going to happen anyway so let’s just carry on and ignore the Mohawks’ concerns,” said Hay. “And that sets the police up to basically educate their own officers that these Mohawks are law breakers; that they don’t have a right to be there. It’s just wrong to do it like that.”

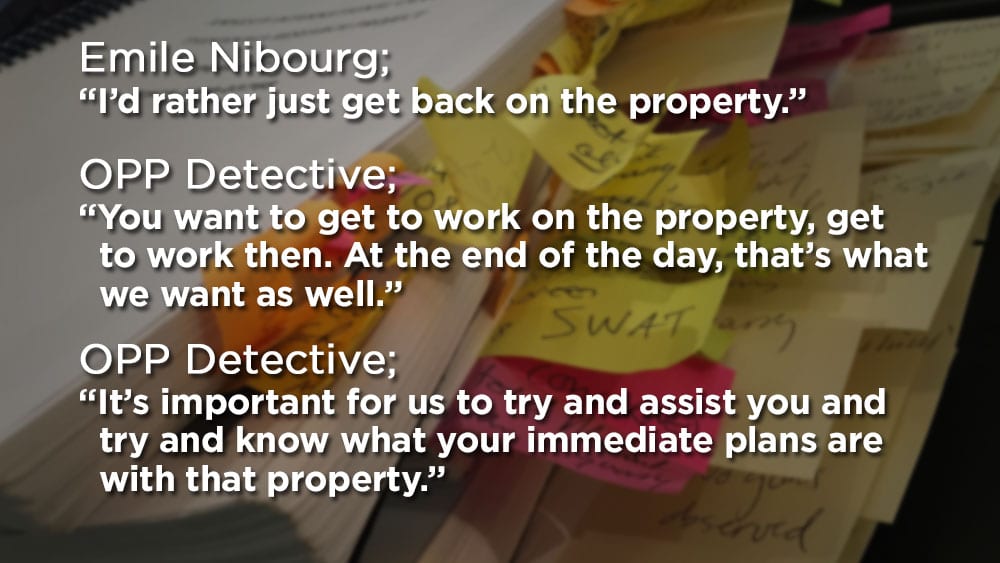

The OPP’s balance between the rights of private property holders and Indigenous rights is further highlighted in an exchange between Theo’s son, Emile Nibourg, and an OPP detective.

In an audio recording, Nibourg made it clear he wasn’t interested in pressing charges against the Mohawks for a minor confrontation on April 11, 2008.

“It’s almost like these white people sticking together against the Mohawks and that’s not being objective,” said Hay. “That’s not a police officer’s role.”

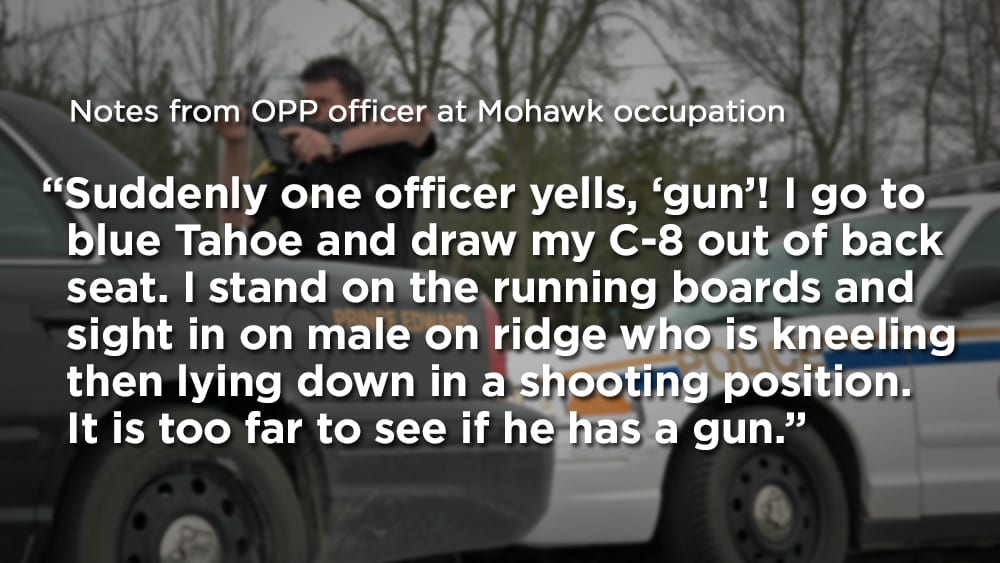

The most serious confrontation happened days after the blockades ended. The OPP made sudden arrests of Doreen and three other Mohawk men near the occupied quarry.

The situation became volatile when an OPP officer saw a young Mohawk man with a stick, and thought it was a gun.

Standing in his kitchen in Tyendinaga, Hay flipped through photos Amnesty collected through its access to information requests.

They were taken on April 25, 2008 showing OPP officers with assault rifles aimed at the Mohawks.

“We came within a hair’s breadth of having a repeat of what happened to Dudley George at Ipperwash,” said Hay.

In 1995, the Objiway land defender was shot and killed by an OPP police sniper, a member of the TRU team, during a land occupation at Ipperwash Provincial Park near Sarnia, Ontario.

An inquiry into the death of Dudley George examined the actions of police and the Ontario government. In the spring of 2007, the Ipperwash Report was released; it included 100 recommendations to avoid a repeat of the deadly violence.

The OPP said it has addressed all of the recommendations aimed at policing. In particular to the Culbertson tract reclamation in Tyendinaga, the OPP said it “recognizes all interests of the involved parties” and the right to lawfully protest.

The OPP provides training for bias-free policing, and cultural awareness. It employs a framework to guide police actions in what it calls “Aboriginal critical incidents.”

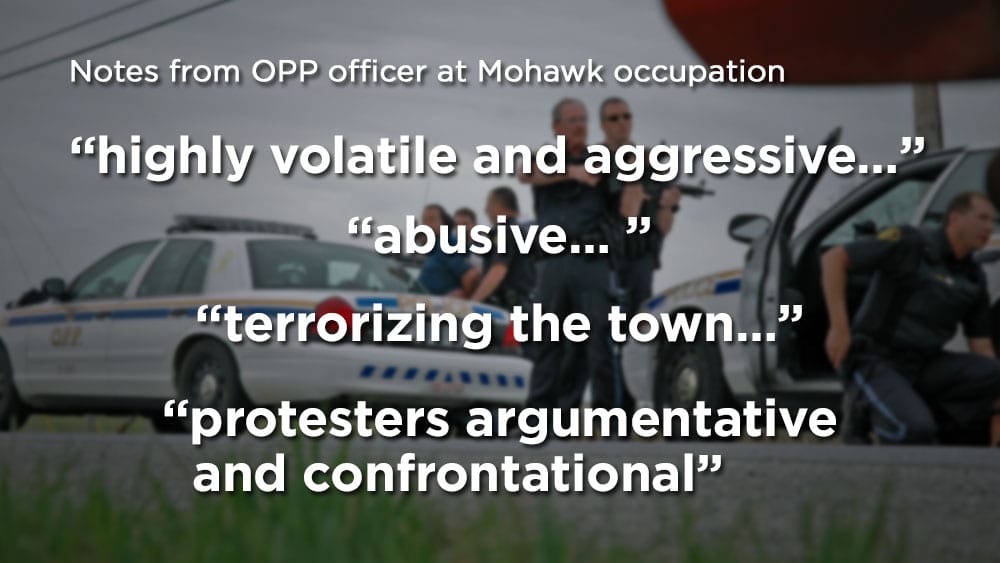

But it’s clear from officers’ notes and other documents, that the OPP viewed the Mohawks as violent criminals, Hays said.

“It’s been my experience,” said Hay, “there’s always a heightened threat perception by police the minute there’s an Indigenous protest and particularly when the word Mohawk is used in the same sentence.”

Amnesty International has asked for a probe or independent review of police actions in Tyendinaga.

Both the OPP and the Ontario Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services have refused.

The OPP and the ministry also refused interview requests from APTN Investigates.

Amnesty International is pushing for police accountability, answers, and an apology to the Mohawk people involved.

Dan Doreen isn’t optimistic.

“I can’t thank Amnesty enough for fighting for the answers that we’re never going to get because it puts the story out,” said Doreen.

“I want the story to be told so that people realize and people know that when they go out and defend the land how they can protect themselves and expect what’s going to happen.”