Warning: This story contains graphic details about the abuse suffered by children in Indian Residential Schools. It may be triggering for some readers.

When the St. Margaret’s Indian Residential School on Couchiching Reserve, Ont., was being torn down during the mid-70s, Rudy Bruyere, a former St. Margaret’s student was rummaging through a former groundskeeper’s house.

What he found that day was something he would never forget, said Curtis Bruyere, the eldest son of Bruyere.

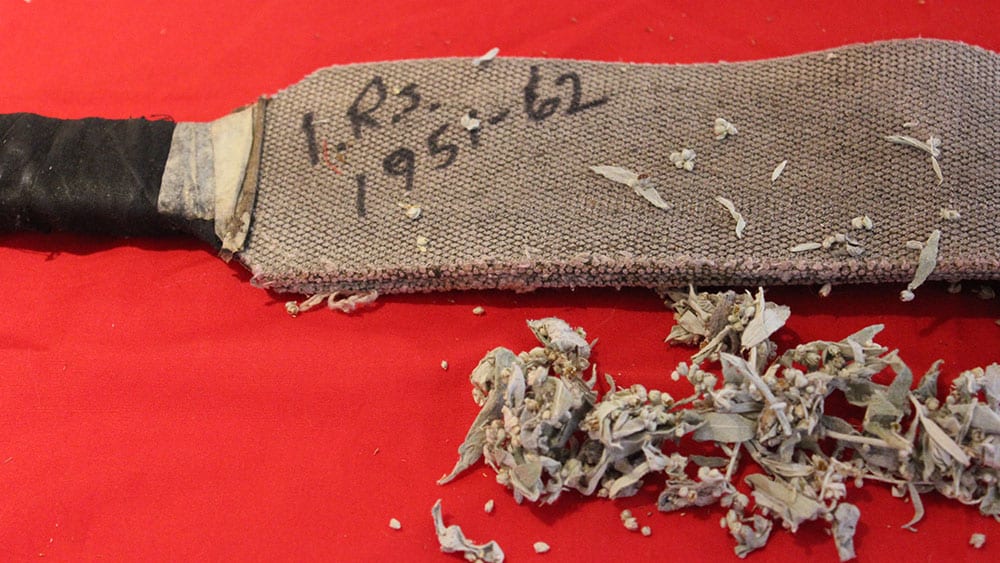

(A handmade strap once used to punish Indigenous children at St. Margaret’s Indian Residential School in Couchiching First Nation, Ont. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

Inside a wall were two straps used at St. Margaret’s to punish young Indigenous children.

Bruyere recognized the straps because he was regularly beaten as a child by at least one of them.

Bruyere was in his early 30s when he made that discovery.

Made out of material from a conveyor belt, the strap is approximately 14 inches in length and half an inch wide.

It appears to have been made from material found inside the school’s nearby wood shop.

APTN Investigates examined the strap first hand.

The strap is worn with black tape on the handle and on the tip of it.

Shockingly, the end of the strap appears to be stained with dried blood.

(This strap was found by residential school survivor Rudy Bruyere, who wrote the dates he attended St. Margaret’s on the back of it. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

On the back of it, “1951 to 1962” is written in permanent black marker. That is during the time when Bruyere attended St. Margaret’s.

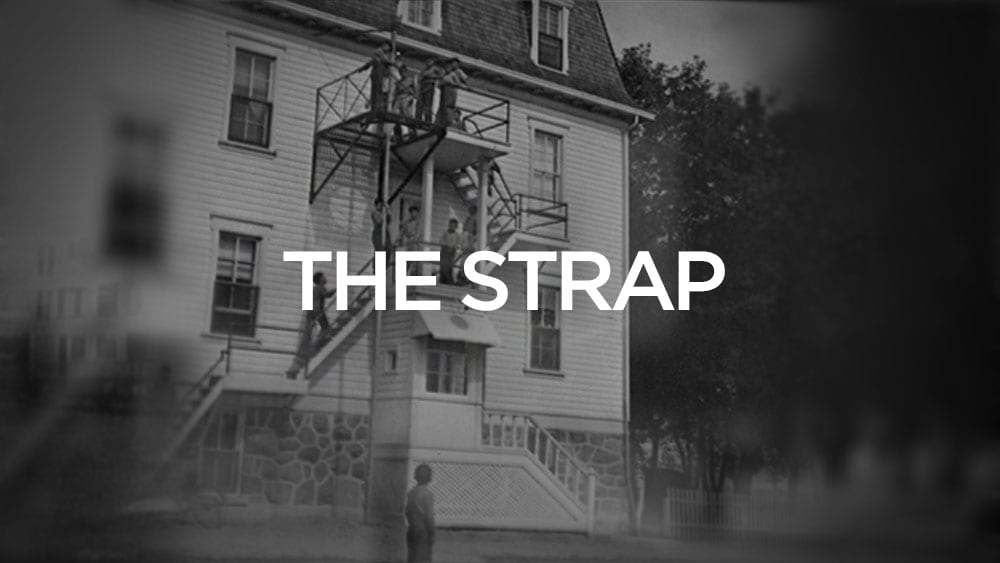

(View of the residential school in Fort Frances, Ontario: ca. 1950. Photo: Library and Archives Canada/Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development)

St. Margaret’s Indian Residential School, also known as the Fort Frances Indian Residential School, was operated by the federal government from 1906 to 1974 and was affiliated with the Catholic Church.

It was one of 130 residential schools across Canada that forced more than 150,000 Indigenous children away from their families and culture as a means of assimilating them into mainstream society.

The schools were mostly government-funded and church-operated from the 19th century up until the last school finally closed in 1996.

(Rudy Bruyere, approximately age 12-years-old. Photo courtesy: Curtis Bruyere)

For approximately 20 years, the strap sat on a shelf in the Bruyere family’s home.

(Ry Moran, director at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation said that before the strap was brought to the centre, staff from NCTR travelled to Couchiching First Nation and participated in a ceremony. Photo courtesy: NCTR)

It has only been in the last couple of years that the strap has been housed at the National Centre for the Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), a place archiving thousands of documents to preserve the history of the residential schools system.

(The Winnipeg-based National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation is home to thousands of documents related to residential schools and some artifacts such as the strap. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

“There is no question this is a very painful artifact,” said Ry Moran, the director at the centre.

“Imagining a child to be hit with this thing is actually horrific, because it is for no other term, this is a torture device.”

Moran said the strap is also very heavy.

No discipline policies or directives at residential schools

Records show that not only were students forced to be away from their families, language and culture but also exposed to corporal punishment and severe sexual and emotional abuse.

The many examples of abuse are well documented. Thousands of former students have been compensated for sexual or serious physical abuse under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

In many instances, students were disciplined for things such as bed-wetting, speaking their language, neglecting chores or stealing food, which was common because many were hungry.

(Boys playing on the fire escape of Fort Frances Agency Catholic Indian Reservation School, Fort Frances, Ontario: ca. 1958. Source: Library and Archives Canada/Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development)

“The residential schools were largely absent from strong policies and that’s where so many bad things happened,” said Moran about St. Margaret’s Indian Residential School.

“The sad thing is, this type of abuse isn’t isolated just to one residential school. It was happening all the way across the country for far too long.”

It is something the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) thoroughly documented in their final report after interviewing more than 6,000 witnesses in its six year investigation into residential schools.

In the TRC report, it explains how the churches and religious orders that ran these schools disciplined based on scripture, stating “corporal punishment was a Biblically authorized way of not only keeping order, but also bringing children to the righteous path.”

Read: A copy of the original policy pertaining to school discipline at residential schools, 1953. Source: Library and Archives Canada – Discipline Policy at Residential School

Prior to 1953, the department of Indian Affairs did not have a policy regarding school discipline.

It was a free-for-all for school staff to discipline students how they saw fit. In one infamous case, a dorm supervisor at the Port Alberni Indian Residential School, Arthur Henry Plint, quit a very high paying job and took a large cut in pay in order to have unsupervised access to children. The judge who sentenced Plint after he was charged with 36 counts of indecent assault and three counts of assault causing bodily harm, called him a “sexual terrorist.”

And Plint was not alone. Many other former staff or clerics have also been charged and convicted.

Although corporal punishment existed in mainstream Canadian schools, Moran said the gravity of discipline used in residential schools was vastly different.

“The difference was there was actually explicit policy around corporal punishment and there were standard issue straps,” says Moran.

“These were savage beatings where people [residential school students] continued to bear real physical impairment and damage as a result of those beatings.”

There were other types of abuse in residential schools. Handmade straps, horsewhips, hockey sticks, metal rods, shovels and fists were reported as being used against the children. Also, food deprivation, hair cutting, ear twisting to public humiliation.

St. Anne’s Indian Residential School in the 1940s. Photo courtesy: Algoma University/Edmund Metatawabin Collection

Among the most horrific was at St. Anne’s Indian Residential School, once located in northern Ontario, where court documents show a handmade electric chair was even used to shock children.

Watch: APTN Investigates: Reckoning at St. Anne’s

Based on various literature, the type of strap used at St. Margaret’s was also reported to have been used inside other schools in different provinces.

The strap at St. Margaret’s was reported to have been used on children’s genitals, something Curtis said his father shared with him one day.

(Canadian historian Ian Mosby said residential school staff were allowed to act with cruelty because Indigenous children were not seen as fully human. Photo: Steve Mongeau/APTN)

This comes to no surprise to Ian Mosby, a historian who has conducted a wealth of research into the residential schools system.

“There’s this constant abuse across the country because there were no specific guidelines. It left abusers open to their imagination when it came to torturing children,” said Mosby.

“At the heart of the system is the dehumanization of children. The infamous assimilationist policy of Duncan Campbell Scott, superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs, to “kill the Indian in the child” allowed teachers and priests and nuns to view the children as savages, and in doing so it allowed them to act with cruelty.”

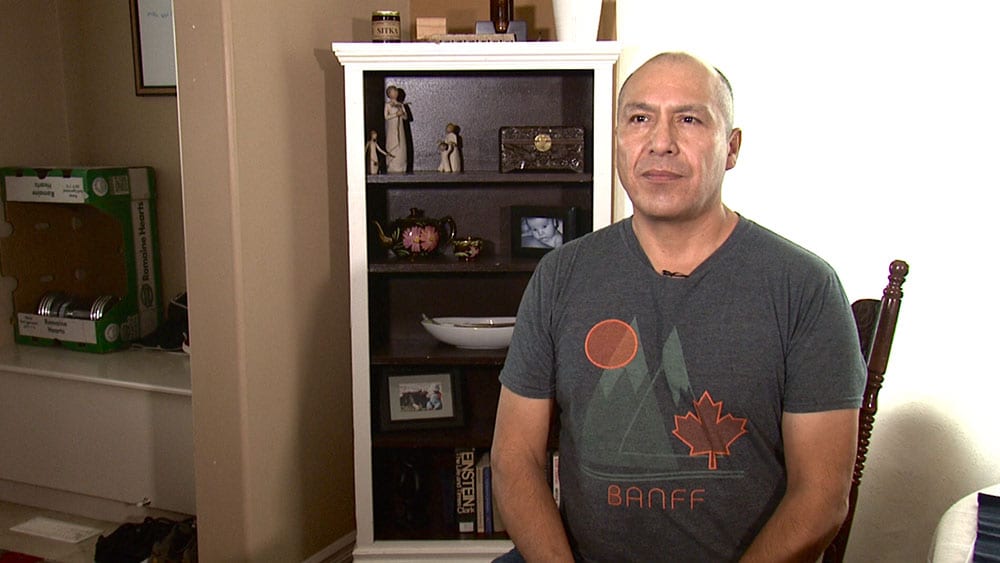

A protector, a loving father and grandfather

Curtis said he remembers seeing the strap in his family’s home from the age of 16 onward, Curtis also reflects on the kind of person his father was.

(Curtis Bruyere is the eldest son of the Bruyere family. He said his father Rudy always spoke out against certain issues whenever he needed to. Photo: Chris Stewart/APTN)

“He loved to be outdoors, he was an outdoorsman. He was the kind of the guy you would want to be in the bush if you were out somewhere,” said Curtis.

(Rudy Bruyere after a hunting trip during the 1990s. Photo courtesy: Karen Chaboyer)

Bruyere was also known as a protector.

“My dad, when he was 14, one of the housekeepers tried to make him fight a younger brother,” said Curtis.

But Bruyere wouldn’t do it. So the housekeeper made Bruyere fight him instead.

“My dad fought him, and then they shipped my dad out to Assiniboia [Residential School] in Winnipeg until he was 16.”

Curtis said his father was the type of person to fight back and to question authority whenever he needed to.

(Rudy Bruyere loved to sing and hum and did this up until his death at the age of 67-years-old. Photo courtesy: Karen Chaboyer)

Although Bruyere struggled with alcoholism for a large portion of his life, Curtis said he understood why.

“It was all that pain, from that upbringing of being taken away from your family and you didn’t know how to deal with it,” said Curtis.

Bruyere passed away on July 10, 2011, he was 67 years old.

Knowing the strap is at the NCTR, Curtis is glad to know the device will be part of telling the history of the residential schools system. He hopes people will learn more about it and the legacy it left on Indigenous peoples.

“That’s why things like this are here. We as a country cannot forget, we cannot be allowed to forget,” said Ry Moran.

“We have to keep telling these stories over and over again until there is not a single person in Canada that doesn’t understand this history.”

If you or someone you know is in immediate need of help, the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day. Please call 1-866-925-4419