APTN News

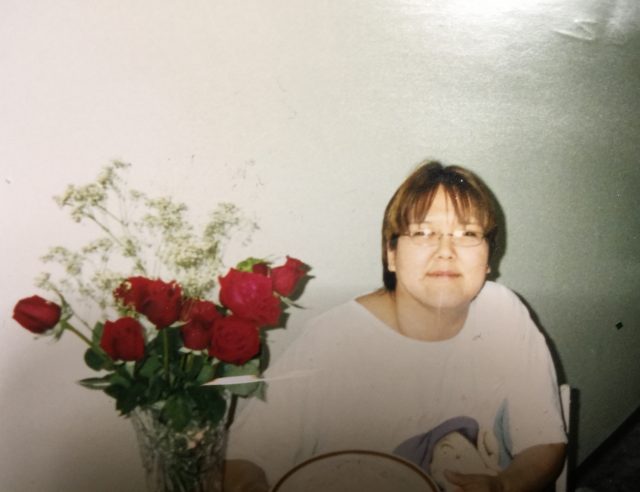

Betsy Kalaserk may have taken her own life as an adult but it was a fate sealed by the abuse she suffered as a child says her niece.

“It was a lifelong suicide,” Laura MacKenzie said Tuesday in Rankin Inlet.

MacKenzie was the first witness to testify at the only stop in Nunavut for the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Kalaserk was found dead 15 years ago in a Yellowknife, NWT apartment. Her husband was charged with second-degree murder but convicted of criminal negligence causing death.

MacKenzie believes the man bears some responsibility for watching and doing nothing to stop Kalaserk, 29, from killing herself.

As do family members who sexually abused Kalaserk as a young girl making her devalue herself said MacKenzie.

“The very ones who should have protected her were the ones that have abused her,” she said.

Mackenzie’s testimony followed an emotional introduction and impromptu song from Inuk singer Susan Aglukark, who revealed last year she’d been sexually abused as a child in Rankin Inlet. Aglukark said the trauma was a root cause of Indigenous suicide.

“We can be healed,” she told the crowd gathered in a Rankin Inlet hotel banquet room.

MacKenzie, a former president of the Rankin Inlet women’s shelter who worked to bring the inquiry here, used her testimony to discuss what she says is still a taboo subject in the north.

She said “rampant” child sexual abuse is covered up despite leading to epic levels of suicide – especially among youth – in the northern territory.

“Sexual abuse is not talked about,” she said. “Many victims hate themselves and have a love-hate relationship with the abuser.”

Aglukark’s abuser, whose identity she has not disclosed, was abused in residential school. He was convicted in 1990 after she and other victims pursued charges.

Yet coming forward can be just as hard, said MacKenzie, referring to the isolation, family shame and reprisals that often follow.

“Let’s quit turning a blind eye to this,” she said. “Maybe society likes to judge victims but being quiet about it is worse.”

The people of Nunavut are still dealing with huge societal and social change. It was only 50 years ago they were enticed off the land “by a wage and a free shack to live in,” MacKenzie said.

What followed was traditional nomadic life colliding with colonization – and the introduction of alcohol and drugs – leading to sexual promiscuity and dysfunction in the family home, she added.

“Many victims such as Betsy end up killing themselves slowly. Because child sexual abuse is a silent killer,” she said.

MacKenzie said “too many family members stay silent” when a child is being abused.

Commissioner Qajaq Robinson noted MacKenzie’s message was like that of the #metoo and #timesup movement, as it is known on social media, that is calling out sexual abuse around the world.

“There’s been this culture of silence,” said Robinson, adding she believes it was starting to come to an end.

Nikki Komaksiutiksak was the second of 20 family members registered to speak publicly and privately over three days in Rankin. She broke down several times recounting horrific abuse she says an aunt inflicted on her and her cousin Jessica Michaels.

The two were famous throat singers who performed around the world as young girls but testified she suffered physical and sexual torture behind the scenes.

“I can’t have wire hangers in my house” she said. “They’re ugly and they hurt.”

Komaksiutiksak said she and Michaels testified against the aunt in court as teens then went into foster care in Manitoba instead of reconnecting with family in Nunavut. Tuesday was her first time back in Rankin in 26 years.

She said she became pregnant at 15 while Michaels became addicted to crack cocaine and ensnared in the sex trade in Winnipeg. Michaels was found dead at 17 in a rooming house that was a deemed a suicide.

Komaksiutiksak said she tried to get police to investigate further but claims they weren’t interested.

She made a number of recommendations to the inquiry, not the least of which was calling for changes to the child welfare system.

“It’s detrimental to take children from family,” she said. “Child welfare needs to find ways to work with family and not against.”