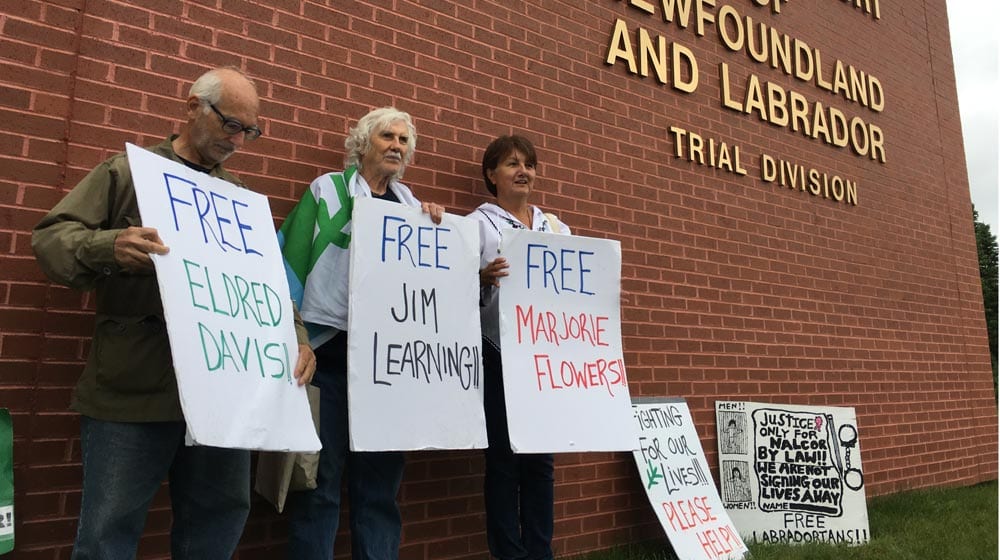

Marjorie Flowers doesn’t consider herself a criminal.

But in July of 2017 she was arrested, put on a plane, and flown more than a thousand kilometres away from her family and community in Labrador to St. John’s, where she spent 10 days in a maximum security men’s prison.

When she returned home, she spent another 30 days under house arrest.

Her crime? Refusing to promise a judge she would stay away from the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project site, which she and dozens of others occupied in the fall of 2016 in a last resort effort to protect their water, traditional foods and way of life from projected methylmercury contamination.

The 51-year-old Inuk mother, teacher and land protector will appear in court in June to respond to civil and criminal charges for violating an injunction granted to the crown corporation building the dam in order to keep land protectors and protestors away from the site. Flowers says she will plead not guilty to the charges.

Flowers’ lawyer Mark Gruchy represents about two dozen people who face charges related to the Muskrat Falls protests. Most of them are Indigenous.

He says his clients feel “very morally justified in what they’re doing, and in fact felt compelled in many instances to be involved in this issue the way they were.”

Gruchy says the injunction and subsequent criminalization of Indigenous people defending their land, food, and way of life were avoidable.

“You have the normal operation of the justice system colliding with a very social complex issue which ought to be dealt with on a political level and never should have got here.”

Indigenous people arrested and jailed for defending their lands and waters. It’s a story that plays out time and again across Canada.

Experiencing ‘ecological grief’

But research out of Labrador is challenging the narrative of the “angry Indigenous protestor” often spun by police, governments, corporations, and media.

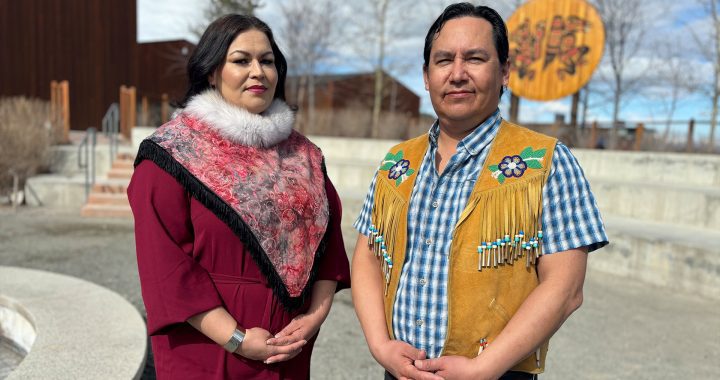

Ashlee Cunsolo is director of Memorial University’s Labrador Institute in Happy Valley-Goose Bay.

She has researched the impacts of climate change on Inuit communities in Nunatsiavut and found that many facing a loss of access to traditional hunting grounds and cultural practices fundamental to their well-being and identity are experiencing what she calls “ecological grief”.

Cunsolo describes ecological grief as “grief that’s in response to a change to a beloved homeland or environment or ecosystem.”

“Being out on the land and feeling their ancestors there, and feeling those memories, and suddenly being cut off from that, not only cuts you off from the experience as an individual but cuts you from that tie of ancestral connection,” she says, describing the way Inuit in Nunatsiavut have been impacted by climate change. “So it was shaking people at a very foundational sort of psychological level, as well as an emotional level, as well as a physical level.

Cunsolo had just begun her new job as director of the Labrador Institute in the fall of 2016 when the Muskrat Falls protests intensified ahead of planned reservoir flooding.

Inuit, Innu, and settler Labradorians united against the controversial dam, in part out of fear of losing access to traditional foods.

That fear was corroborated by a peer-reviewed scientific study led by Harvard researchers that projected downstream communities would be exposed to unsafe levels of methylmercury through traditional foods like fish and seal unless vegetation and topsoil were removed from the dam’s reservoir prior to flooding.

Cunsolo says the way people transformed their grief into action was unlike anything she had previously seen.

“Feelings of anger or frustration weren’t at the fore; it was people wanting to come together to talk about the river, and to share stories about the river,” she recalls.

“It wasn’t fighting against, it was fighting for, and feeling that commitment to all the people who had come before you and had loved that river, and wanting that love to continue forward, and that access to the river to continue forward.”

There are known and acceptable ways to grieve and mourn the loss of a loved one, Cunsolo explains. But when humans face the loss of lands and other non-human entities that they have a deep spiritual connection with, there are no universal ways to grieve.

“But when people come together to share in grief, and to share in strength related to that grief, that is a moving, profound, unstoppable force,” she says.

Cunsolo noticed that after land protectors breached a gate at the Muskrat Falls site on Oct. 22, 2016, and subsequently occupied the site, the corporation and police attempted to frame the protest as violent and to suggest the safety of workers on site had been compromised.

“I think we saw this amazing thing play out in Muskrat Falls where people were almost trying to force a framing on it that was just assumed because it was a quote-unquote protest,” she says.

“I don’t think that we necessarily know how to deal with [ecological grief] — in media, in court injunctions, in the legal system, in mitigation and adaptation strategies, in policy.”

The peaceful occupation of Muskrat Falls continued for four days until Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Dwight Ball held a marathon meeting with Indigenous leaders and reached an agreement that included demands set out by land protectors.

Policing Indigenous protests

With the exception of nine arrests at a blockade days prior to the occupation, there was no major police intervention in the land protectors’ occupation of the site and no violent arrests of Indigenous people.

But Flowers and others involved in the Muskrat Falls resistance say that since the occupation they’ve been followed, pulled over and approached by RCMP officers in Labrador.

Denise Cole, who has been protesting Muskrat Falls since before the project’s inception, was charged with violating Nalcor’s injunction after she performed ceremony near the river.

“This idea that rule of law, colonial law, has to be enforced at all cost — that’s sent a level of fear and trauma and knowing that your voice is not an important voice in the justice system at all.”

Flowers says the repression she says she and others feel from the injunction and the RCMP’s enforcement of it makes them feel like they “couldn’t even breathe.

“I felt like I was losing my breath, because of the power from the outside, from the colonialism—the government, the corporation itself, the law enforcers. Everything was onside.

“It makes me want to scream my head off. The oppression is just so present. And there’s nothing—not a thing—I can do about it. I feel like we’re just kind of like these plastic bottles on these big waves in the ocean. We don’t have any control. We just get bounced around, into court, back out of court.”

She says she sees local law enforcement as “puppets that have to do their work,” but at the same time, they’ve caused her a lot of stress.

“It was starting to affect my work. It was affecting my relationship. It was affecting everything. I was feeling a lot of anxiety from it because I felt like I couldn’t go outside my house. I couldn’t go to the dental office — there was a cop behind me [while I was] making an appointment.”

Shiri Pasternak, an Assistant Professor of Criminology at Ryerson University, says what’s happening to land protectors in Labrador is playing out with other resource development projects on Indigenous lands across Canada, where corporations are increasingly turning to courts for injunctions when Indigenous land and water protectors threaten corporate profits.

“In order to justify, in order to authorize the RCMP and police forces to enforce [Canada’s] and these companies’ access to Indigenous lands, they need to secure legal authority, and they do that through the injunction,” she explains.

She says the RCMP and other police forces often surveil, follow or approach Indigenous people who defend their land — tactics collectively referred to as “soft policing”.

“Rather than looking like violent repression they work in more covert and subtle ways in terms of letting people know they’re being watched in the hopes that people will self-police not to get involved in things because they’re intimidated.”

Jeffrey Monaghan, an Assistant Professor of Criminology at Carleton University, recently co-authored a new book with his colleague Andy Crosby called “Policing Indigenous Movements.”

In it, the authors disclose RCMP documents obtained through access to information legislation that shows the national police force operating in what Monaghan calls a “conservative culture” in how they understand and treat Indigenous land and water protectors.

Those documents show RCMP referring to Indigenous people resisting Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline in British Columbia as “violent extremists,” and the entire Mi’kmaq-led movement to stop shale gas exploration in New Brunswick as a “violent extremist anti-fracking movement.”

Watch Part 1 of Justin’s story on Ecological Grief.

“We see a dramatic increase and a rise in terms of national security resources and national security language starting to focus their attention, target, and police Indigenous movements with more and more intensity,” Monaghan explains.

“You have an intensification of surveillance, you have more and more resources, and of course you have a reframing of a local conflict over land, over complex histories, being reduced to national security, notions of extremism, and being really reframed as very criminal and violent threats.”

Pasternak and Monaghan both point to the concept of Canada’s “critical infrastructure,” which they argue the government, police, and corporations are working together to protect from Indigenous people who don’t want pipelines, dams and other developments they say are harmful on their lands.

“In different bureaucracies, institutions at the national security level of policing, they’ve patched in all kinds of relationships and partnerships with private corporations that allow private corporations, which include the kind of energy branches of large energy corporations as well as private security who are employed by these corporations, to feed in intelligence, to do their own forms of surveillance and feed in intelligence that goes into policing databanks [and] into policing intelligence resources.”

“Exhausting” but worth the fight, say land protectors

Beatrice Hunter, an Inuk grandmother and land protector who was the first of four from Labrador to stand in court and say ‘no’ to the injunction, and subsequently do time at Her Majesty’s Penitentiary in St. John’s, says navigating the legal system while being under the watchful eye of the RCMP has taken a toll on her.

“I never thought I’d be caught up in the court system,” she says. “I was never a lawbreaker, so it’s a very tiring, exhausting process and I hope I don’t get burned out.”

Watch Part 2 of Justin’s Ecological Grief.

At the same time, she says, “my ancestors cry out to me all the time, telling me that this is our land. So I get strength from my ancestors.”

Hunter says she has “lost hope with the provincial and federal government,” and that “it seems that corporations are running the government.”

While she and others continue to resist Muskrat Falls, Cole says a strength is building among Indigenous communities across Canada, “because we all recognize shared oppression and devastation to water, and devastation to land.

“There’s a collective truth that’s spreading throughout Turtle Island, and it’s that our colonial oppressors are never going to be truthful. They’re never going to try to reconcile. They’re always going to try to manipulate and make deals — and if it isn’t us as people who make these changes, they won’t happen.”

Kim Campbell-McLean also faces charges related to the Muskrat Falls protests. She was among the land protectors who occupied the work site in 2016.

The Inuk women’s advocate from North West River spoke at the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Inquiry hearings in Labrador in March and cited large resource development projects like Muskrat Falls as one of the barriers Indigenous women and children face to accessing traditional foods, and to becoming less dependent on violent men.

“Mining. Dams. It’s destroying our food sources for Inuit women and children,” she told the Inquiry.

Campbell-McLean later told APTN in reference to the Muskrat Falls occupation and the charges she faces that she would “do it all over again — and I would do it every day of my life if I had to, in order to protect that for our women and our children and our culture, and our integrity and our values as people.”

Charlotte Wolfrey, an Elder from the Nunatsiavut community of Rigolet, also faces charges for resisting Muskrat Falls.

She says she participated in a blockade of the Muskrat Falls site days before the occupation in October 2016 because it “was a matter of continuing our culture like it was — our continuance as a people, really.”

She agrees with Cunsolo’s assessment of ecological grief as a driving force behind the Muskrat Falls protests, and also argues that Inuit have a unique obligation to their ancestral lands, waters and resources.

When she went before a judge last year, she explained this to him.

“He asked me if I understood the charges, and I told him I understood I had broken some of Canada’s 150-year-old laws. But that when you’re Indigenous there’s laws that sustained us for 6,000 and 7,000 years — the law to protect the land and water and things that sustain you.”

Cunsolo says the Muskrat Falls protests hold a valuable lesson, not just to those involved.

“I think that Muskrat Falls, if we step back from it and look at it and what is it’s significance in history in this area in Canada, I think one of the things that it’s teaching us is: If we really look at all the different pieces that happened and we start to tell this complex story, there are key learnings about grief and people coming together in a painful way, but also in a resilient way.”

Flowers says it isn’t lost on her that the forces that threaten to take away her people’s river, traditional foods and way of life are the same ones trying to prevent her from resisting.

“The government has historically and continually come into our land, into this land, without proper consultation, and taken what they wanted without giving anything back,” she says.

“There’s oppression and suppression, and people are stripped of their rights and they can’t stand up unless there’s force,” she says. “And that’s what I felt like I came to; when I laid on the ground those many times, I said to hell with it — somebody has to do this. We have to take the stand because otherwise what do we have left?”

APTN reached out to Nalcor Energy, Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Dwight Ball and RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki for this story, but none granted an on camera interview before the story went to air.

This cultural and personal commitment and love of the native land as life itself is natural and sacred . When the rape of the land and waters continues now , unabated due to the greed and ignorance of corporations and governments -it is important to get the message “out there ” that these land -keepers are not violent criminals. They are in fact suffering ECOLOGICAL GRIEF.. How can city -dwellers, who conceive of the mother earth and her waters as a “product to be sold ” ever grasp that it is also their own roots that they are pulling up , to shrivel and die ?

AWESOME coverage Justin! Cannot put into words my gratitude

This cultural and personal commitment and love of the native land as life itself is natural and sacred . When the rape of the land and waters continues now , unabated due to the greed and ignorance of corporations and governments -it is important to get the message “out there ” that these land -keepers are not violent criminals. They are in fact suffering ECOLOGICAL GRIEF.. How can city -dwellers, who conceive of the mother earth and her waters as a “product to be sold ” ever grasp that it is also their own roots that they are pulling up , to shrivel and die ?

AWESOME coverage Justin! Cannot put into words my gratitude