Justin Brake

APTN News

The Muskrat Falls hydro project in Labrador is nearing completion amid widespread concerns and opposition from residents of communities downstream of the controversial dam.

A symposium in Happy Valley-Goose Bay this week brought together researchers, community leaders and land protectors. They shared observations and concerns about the project’s economic, social, cultural, political, environmental and human health impacts.

Opposition to the dam began before the environmental assessment process in 2011 but made national and international headlines in October 2016 when land protectors occupied the project’s worksite for four days.

The grassroots-led movement was responding to project proponent Nalcor Energy and the province’s downplaying of peer-reviewed scientific research that projected reservoir flooding would lead to an increase of methylmercury, a dangerous neurotoxin, in country foods Innu, Inuit and settler Labradorians in five downstream communities depend on.

The study, led by researchers at Harvard University, recommended extensive clearing of the dam’s reservoir prior to flooding to adequately reduce the amount of methylmercury production. Nalcor and the province initially said clearing wasn’t an option.

But with the Muskrat Falls site occupied and construction shut down, Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Dwight Ball called an emergency meeting with Labrador’s three Indigenous leaders.

They reached an agreement that included plans to form an independent expert advisory committee to assess the risk of methylmercury production and options for mitigation.

After lengthy delays the committee’s work is now underway, but some aren’t confident that even if it recommends extensive mitigation measures Nalcor won’t do enough to protect locals’ health.

“As Inuit we’ve hunted and fished and harvested food from the lands since time immemorial. It’s such a huge part of our culture,” says Labrador Land Protector Amy Norman.

“For them to only really seriously look at the methylmercury issue once it’s already 75, 85, 95 per cent done, the Muskrat Falls project, it really is too little too late I think.”

Local musician and Labrador Land Protector Jacinda Beals recently interviewed residents of Mud Lake to hear their concerns.

The remote community of 50 flooded last spring and residents were airlifted to safety in an emergency evacuation.

Homes were destroyed and some residents haven’t returned to the community.

They say in Mud Lake’s 200-year history flooding of that magnitude had never occurred and they doubt the findings of an independent study that determined the event was not a result of Muskrat Falls.

In a series of on-camera interviews published by Beals on the Labrador Land Protectors’ Facebook page, Mud Lake residents say they are living in fear of the dam.

They share the belief of many, including leading experts who are not associated with the project, that the dam is being built on an unstable sand and clay foundation that won’t hold once reservoir levels are brought up.

“They are terrified,” said Beals, explaining one person she interviewed is sleeping with a life jacket under their bed.

“Every single interview, you could see it written on their faces how stressed they are. Twelve people interviewed, 12 people broke down telling their story. Four people have been diagnosed with PTSD. They worry about this every single day.”

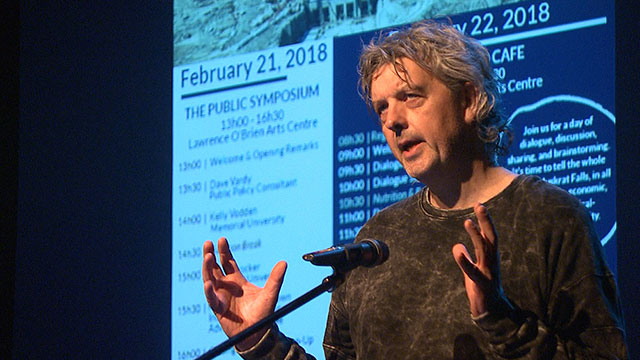

Memorial University sociology professor Steve Crocker presented at the symposium Wednesday.

He said that “by all accounts, Muskrat Falls is a terrible failure that will make us poorer, colder, hungrier and sicker.”

Crocker argues the provincial and federal governments have failed to protect the people of the province, who will endure financial, energy and food insecurity as a result of the dam.

“Instead of providing security to the citizens and externalizing volatility into the market, they download the volatility of that market onto citizens with the hope that they can thereby tap into markets, gain more money, etc.,” he explained.

“But the net result of that is the production of a population that can’t absorb those costs and become a kind of collateral damage or an injurable population.”

Tracey Doherty, a Nunatsiavut Beneficiary and Inuit Bachelor of Education student who led a discussion at the symposium on Indigenous rights, said Muskrat Falls “undermines our cultural health — it’s just that simple.”

She said while she appreciated Justin Trudeau’s apology to residential school survivors in Labrador last fall — in which the prime minister acknowledged Canada’s role in harming and assimilating Inuit and Innu children and youth — supporting Muskrat Falls with loan guarantees makes the government complicit in actions that will render similar outcomes.

“Muskrat Falls is that same process: cultural genocide,” she said. “And for federal loan guarantees to continue — they need to take a good look at that, that they’re still being agents of cultural genocide.”

As protests against the project ramped up in October 2016 Norman and others wrote an extensive letter to the United Nations, explaining how Muskrat Falls contravenes the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which the Trudeau government had recently signed.

She said after local political and legal institutions failed to protect those living in the shadow of the dam, the group felt they had no choice but to appeal to the international body, which has previously sent staff to Canada to observe conflicts between Indigenous peoples and the state.

But to date the U.N. has not responded to that letter, Norman said.

“It’s hard to not get really cynical and frustrated with the entire process because it does feel like we’ve approached this issue from every possible avenue,” she explained. “We’ve appealed to every level of government, we’ve appealed to our Indigenous governments, we’ve appealed to the United Nations. I don’t know that there’s more that we can do.”

Roberta Benefiel of Grand Riverkeeper Labrador is a longtime critic of Muskrat Falls. On Thursday she led a discussion on emerging resistance networks.

Recognizing the provincial and federal governments and Nalcor weren’t doing enough to protect locals’ health and ways of life, she embarked on a speaking tour of the Northeastern United States, some of those states slated to receive power from Muskrat Falls.

After speaking in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts and New York, Benefiel said she feels optimistic opposition to Muskrat Falls will grow.

“It was a really good fit that we were able to talk to them about what’s happening here on the environmental side, on the socioeconomic side, what’s happening with methylmercury, what’s happening with the North Spur and how people are going to bed at night and worrying about whether or not that dam is going to break,” she says. “And that gave them fuel and it gives us fuel and we have formed a coalition.”

Land protectors have been arrested and elders jailed for refusing to stay away from the Muskrat Falls site.

The project’s current price tag sits at $12.7 billion and construction two years behind schedule. First power is now expected by late fall 2019.

While hope for many in Labrador has diminished, some feel they have no choice but to keep fighting.

“There’s 60, 70 land protectors that were forced to go through the court system, and all these people are people that have never been in court, or been arrested before,” said Beals.

“It’s overwhelming. People have been fighting this for years and years. And just to have to live with this everyday — if you’re not fighting it you’re feeling bad for not fighting for it, you feel guilty because you’re leaving your friends and family at risk. You just feel the need to fight as much as you can, as best you can, and we’re doing the best we can here in Labrador.”

jbrake.ca