Kenneth Jackson and Kent Driscoll

APTN National News

The minister responsible for Inuit foster children sent to live in group homes out of territory couldn’t respond to questions Tuesday on how his department monitors their care thousands of kilometres from home.

Family Services Minister Johnny Mike was asked to respond to an APTN National News investigation posted online Friday in the Nunavut legislature that found the territory spends about $9 million a year having 65 kids live predominately in group homes in western provinces and Ontario.

Iqaluit-Niaqunnguu MLA Pat Angnakak put questions to Mike Tuesday while the legislature was sitting.

She asked Mike what specific steps the government is taking to monitor how the children are cared for out of territory.

Mike didn’t directly respond, basically saying the kids sent out of territory have needs the territory can’t provide.

“My question was answered?” said Angnakak. “I did not get an answer. Can he speak on how the Department of Family Services monitors and oversees the services and care being provided to Nunavut children and youth, who are receiving care outside of the territory?”

Mike responded: “I finally understand the question, I will have to get back to the member on her question.”

Angnakak told APTN the practise needs to stop and the government needs to make it a “priority” to bring all the kids already in them back home.

Ottawa is where most of the kids are, spread out among seven different group homes.

Some stay in the homes for years and are supposed to require medical or special needs care the territory says it can’t provide.

But that can no longer be an excuse said Angnakak.

“They always say ‘we don’t have the facilities.’ Well, let’s start building these facilities. We need to try to make it a priority,” said Angnakak. “We need to provide services closer home.”

APTN’s investigation focused one boy’s experience in Ottawa, who APTN can’t name because he’s still a ward of Nunavut.

“Jacob” was 13-years-old when he was taken from Nunavut and put in a group home. He’d call his sister several times a day, every day crying when he first arrived.

He spent over three years in two homes losing the Inuktitut he knew by the time he returned home this past summer.

His time in Ottawa was an immediate struggle. Kids at school learned he had epilepsy and would tease him trying to trigger a seizure.

After assaulting a student and a group home worker Jacob found himself in the court system. APTN was able to piece together what happened to him in documents obtained from the court.

Shipping kids out of territory is supposed to be the last resort, after all other options are exhausted according to the director of Children and Family Services.

But Jacob’s sister told APTN she tried to get him out of Ottawa and pleaded with his longtime social worker to give her custody.

Documents show that the social worker later denied the sister ever contacted her office.

The department has refused to comment on the social worker’s record.

Meanwhile, there are 40 Inuit kids right now in Ottawa, and 34 of them are in group homes. The homes make about 80 per cent of $9 million spent annually to ship the kids out.

“I don’t believe the answer is sending Nunavut youth down south,” said Angnakak. “I don’t think we should just send them down south. They are away from their family and away from everything they know.”

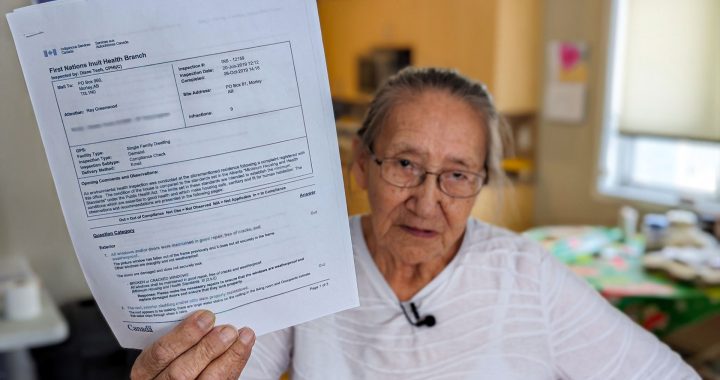

Nunavut’s child and youth advocate also responded to APTN’s story saying it came as no surprise.

Sherry McNeil-Mulak said in the last year her office has responded to seven cases involving children placed in group homes.

“We have observed a lack of culturally appropriate care, a lack of assessments, a lack of coordinated care and communication amongst service providers and families,” said McNeil-Mulak.

She said the cases have shown there is no general plan in place when the kids are first placed in the home, or when for when they get to leave.

“We have also noticed that young people are often not included in these big decisions about their lives,” she said. “They are often treated as passive bystanders, rather than active participants.”

Angnakak said Nunavut has to do better even if foster care or medical services are hard to find in the territory.

She said if that means hiring professionals outside of Nunavut then it should be done. She said Nunavut should also rely on “our own experts … and employ our own people.”

“We need to start now,” said Angnakak.

McNeil-Mulak agrees.

“The Government of Nunavut should actively explore viable options to provide a more diverse range of care options to young people in their home territory,” she said. “It is clearly in the best interest of the majority of young Nunavummiut.”

In the meantime, she said there is “undoubtedly substantial room” to improve the care right now for the children outside of the territory.

All these years, Nunavut has paid a consulting firm in Ottawa to manage the children on a contract basis. According to the company’s website it has one social worker assigned to out of territory children. Nunavut said it plans to hire a permanent social worker by the end of the year.

-Clarification: Since this story was published APTN learned the consulting firm didn’t have their contract renewed as of March 31. An updated story on this can be found here.