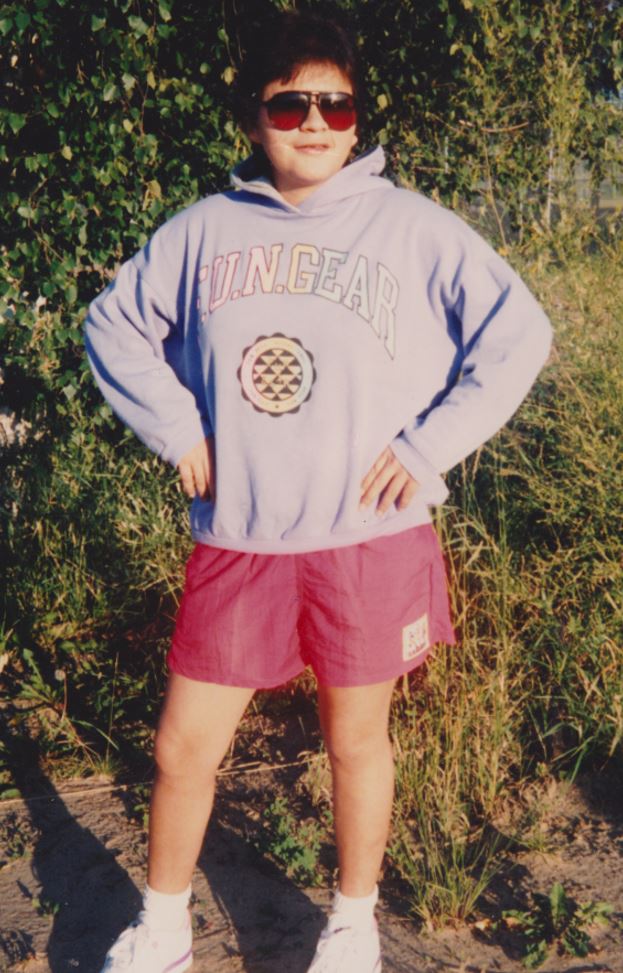

Marlene Carter as she used to appear and how she looks now after years behind bars.

It was in the early months of winter in 1984 when Marlene Carter picked up a loaded .22 calibre rifle and pointed it at her chest.

Then she somehow managed to pull the trigger sending a bullet through her right lung.

She was just 12 years old, but the little Cree girl wanted to end it.

Taking her own life would put a stop to her living hell during those cold days on the Saulteaux reserve in Saskatchewan.

The rifle belonged to her father who had been abusing her. She “couldn’t stand it anymore.”

He wasn’t the first to touch her.

Even at that young age, a trio of Carter’s uncles had forced her to perform unspeakable acts for years while she lived with an aunt. One day in the summer of 1983 — right around her 12th birthday — her father finally pulled her from the home.

She may have thought her dad was coming to her rescue, but the abuse continued when they got home.

She took refuge at the end of a gun.

But Marlene Carter didn’t die that day — years later she would tell a jail psychiatrist that she wished she had aimed “slightly to the left.” That way, the bullet would have hit her heart and ended a tortured life with too few moments of happiness.

Today, the 44-year-old Carter has been inside a jail or secured mental health facility since 2009, often finding herself in restraints or locked in a secure room. She faces the real possibility of never getting out.

For more than a month, APTN National News has reviewed large volumes of documents that trace Marlene Carter’s life from birth and that of her ancestors who hail the same area as one of the first federally-funded residential schools that opened near North Battleford, Saskatchewan in 1883.

This is the story of the Stone Mountain Woman.

Carter suffers from severe mental illness likely caused by years of trauma. She has attempted suicide many times. Doctors say that may play a part in why she lashes out at jail nurses and guards in whatever institution she is placed, records show.

Staff literally applaud when she is transferred. They did earlier this month at the Brockville Mental Health Centre in Ontario, when Carter was sent back to the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Saskatoon.

Carter also hurts herself.

She is known to repeatedly bang her head against walls and floors, only calming at the site of her own blood. The years of head banging has left Carter with a permanent contusion and a scar down the centre of her forehead.

Carter’s erratic behaviour has made her one of the more difficult inmates in Canada for staff to handle. And they’ve been criticized for simply restraining her to a bed or chair for days on end, or locking her in a room.

For some, Carter is also the most dangerous.

“This woman has permanently ruined my life,” one of Carter’s victims wrote in an recent e-mail to APTN National News. “I am just one of the countless correctional staff that have been attacked and assaulted by this woman.”

Ten years ago, Carter was convicted of hitting the former jail guard in the head and upper body, one of dozens of convictions for varying degrees of assault on staff and inmates.

The former jail guard said her anger for Carter still boils after all this time and would like nothing more than to see Carter locked away until her last breath.

But Carter doesn’t hit everyone she encounters and told APTN in January the restraints make her want to lash out. Many people who have helped Carter over the years have said she never laid a finger on them. In fact, they describe a gentle soul, who likes to giggle and pray in Cree.

She’s also someone who yearns to get out — to feel the earth under her feet.

These are the people who think hope is not lost for her – her sisters, stepmother, elders, doctors and Kim Pate, the executive director of the Elizabeth Fry Societies, which advocate for the rights of female inmates in Canada.

Pate has known Carter for nearly 20 years and believes an institutional facility is only making her worse.

With properly-funded community supports, Pate believes Carter can return home to Onion Lake one day and lead a life free of the shackles she likely finds herself in at this very moment.

“I would put my life on it,” Pate said.

Onion Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan, near the border of Alberta, doesn’t have those supports. Will they be in place when Carter’s current sentence ends in the fall?

The answer comes down to whether the federal government is willing to pay for it.

The only thing that is certain is that for the first time in Carter’s life, she has more people who are trying to help than ever before.

Many argue Carter is the result of the effects of residential schools that robbed her people of their identity and put them on a path of inevitable destruction.

It’s a wrong they’re still trying to right to this day.

Abandoned at birth

Marlene Jane Carter was born on June 13, 1971 in Raymond, Alta. to Helen Carter and Tony Swimmer. It wasn’t a happy a day like births tend to be.

No one was rushing to the local newspaper to announce the birth.

In fact, Helen Carter and Swimmer were no longer even together.

Carter was borne into a broken home and it’s suspected her mother had been drinking while pregnant, according to records.

The story of what happened to Carter differs depending on who you ask.

Carter’s half-sister Peggy Harper said Helen Carter wasn’t allowed to bring her home, as she was with another man who wanted nothing to do with Swimmer’s baby.

Others say Helen Carter didn’t want her new daughter and left her in the hospital.

Either way, when she was just three-days-old, Carter went to live with Swimmer and his new partner Annabelle Knight.

“The hospital called for Tony and said that his daughter was born and to pick her up because her mom said she didn’t want her and had left her at the hospital,” Knight said in a Gladue report written for Carter in 2013, that looks at the history of the Indigenous person facing incarceration.

It was a volatile home in Saulteaux, about 50 kilometres from North Battleford.

Both Knight and Swimmer were alcoholics and he’d often beat Knight. Records show Carter repeated Grade 1 three times. By the time Carter was seven she was sent to live with her great aunt. Knight had left Swimmer to get sober and get away from his fists.

But according to court documents and interviews with family, life didn’t get better.

“She endured emotional and physical abuse and was said to have been sexually abused by three of her great uncles,” wrote Justice S.P. Whelan in 2014.

Peggy Harper said Carter was “passed around to drunk men…”

Carter was also forced to wear dresses while living with her aunt, even though she didn’t like them said her half-sister Tanya Moosomin, who lived 50 yards from Carter during this time.

“You see we weren’t allowed to interact with Marlene. (My aunt) forbid it,” said Moosomin. “So we used to sneak around. We’d hug and try to play as much as we can but when (my aunt) got home she always knew Marlene came over and for that she was beaten.”

Moosomin said she remembers crying and asking why they weren’t allowed to play outside with her sister. It was something a child couldn’t understand.

Despite all that Carter was going through, she’d try to be happy.

“It was like no matter what she would always laugh and reassure us we’d play again or she’d be back anyways,” she said. “She has such a good, heartfelt laugh.”

Moosomin remembers the night Carter shot herself and that they weren’t allowed to see her in the hospital where she spent two weeks recovering from the wound, including a collapsed lung.

The suicide attempt was somewhat successful, as children services were alerted for the first time and became involved in Carter’s life.

According to documents, it doesn’t appear Carter suffered anymore abuse.

But attempts at suicide continued, including trying to slash her wrists. She was diagnosed with mood disorders at 13.

After stays in various hospitals, including psychiatric wards, she was placed with other family members.

Carter would hum and rock back and forth when asked to speak about her past during that time.

Soon she’d find herself in a group home on Onion Lake where Peggy Harper was living.

“This was the first time I knew I had a young sister,” she said. “I did Marlene’s hair, gave her some of my finest silk shirts.”

Within minutes, Carter was pulling at her hair because she didn’t like the perm. Harper said she cut the hair short and Carter was happy.

From there, Carter would end up in various youth detention centres in Saskatchewan.

At 14, the court ordered Carter to attend a youth residential treatment centre for behavioral and substance abuse for about two years.

She got a 16-month sentence at 17 years old for robbing a gas station with other kids in 1989.

Over the next few years she’d live in and around the streets, racking up a few more convictions, until she met a much older man and came home one day in 1992.

“Then to my surprise she met a man. She brought him down to meet us and told us the news she was pregnant,” said Moosomin.

The love of a child

From all accounts, Carter was happy when she had her first son, Dallas. She’d quickly have two more sons, Rocky and Robin, with the same man. For a time she was able to stay away from alcohol; drink had plagued her since she shot herself as a child.

“She was so happy when she had her first boy,” Annabelle Knight told APTN.

But motherhood was difficult for Carter, and within a few years she lost custody of the children when she started drinking again. It was around the time one of her closest siblings was hit and killed by a drunk driver.

In despair, Carter tried to hang herself.

“It will appear this later injury resulted in a substantial lack of oxygen to the brain that could have become the origin of a lot of her current mental disturbance,” said Dr. Mansfield Mela in 2011, during a jailhouse psychiatric assessment.

After the botched hanging, Carter started banging her head and experienced vivid images of people’s heads being “chopped off” and her son’s being harmed, records say.

Carter had no criminal convictions between her conviction for mischief in 1992 and Nov. 14, 1998, when she was charged with non-violent crimes.

Since that time it’s been a downward spiral.

At her Jan. 28, 1999 sentencing, her lawyer said Carter’s past “shows a very unhappy and I’d say wretched existence with ongoing problems that culminated in an attempted suicide as of November, falling right into the pattern of these crimes before you.

“I’m at a bit of a loss at what to suggest that you do for this woman. I’ve spoken to her, and she’s not even sure. It appears that the difficulties are ongoing and the problem’s very deep rooted.”

Carter was sentenced to nine months in the Pine Grove institution.

In the Pine Grove sewing room, she stabbed another inmate in the back with scissors and got two years added on to the original sentence.

“Fuck, Marlene, what did you do that for? You bitch, you stabbed me,” the victim said at the time.

“I just did it, I don’t know why,” she said laughing. “Oh fuck, I hope she’s ok.”

Years later, Carter said she stabbed the woman because she was in for raping a 13-year-old “Indian girl”.

She got two more years in July 2000 for assaulting another inmate during a “riot.”

By April 2003, she’d pleaded guilty to uttering threats. Carter was on probation at the Saskatchewan Hospital and trying to reintegrate into the community when she threatened to stab a roommate there.

She pleaded to two more assault charges in October 2003 while she was in the community, where she said she drank and got in a lot of fights.

Back inside, Carter assaulted eight people and pleaded guilty in November 2004.

She remained in the community from 2006 to 2009, when she got 30 months for four counts of assault.

She hasn’t been free since and while in the Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC) in Saskatoon she’s racked up dozens of assaults on staff. She’s also had over 100 head-banging incidents.

The Saskatchewan Attorney General’s office unsuccessfully tried to have Carter labelled a dangerous offender in 2014.

Justice Whelan found the assaults were at the “low end” and “Ms. Carter’s circumstances demonstrated a reduced moral blameworthiness.”

Whelan also blasted RPC for its “inhumane” treatment of Carter who was kept in restraints for months at a time.

“When she was strapped to a hard board over extended periods of time, (that) was inhumane,” Whelan said in her decision. The judge found it unclear from institution records if in fact Carter had been put in restraints as punishment, which is prohibited under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act.

Whelan found the public would be “shocked” at the number of times, at least 35, pepper spray was used to stop Carter from harming herself.

“It merely served to increase distress,” said Whelan.

Set up to fail

In the summer of 2014, Carter was transferred to the Brockville Mental Health Centre to take part in a new program designed for female inmates suffering from severe mental illness.

It was part of an agreement between the Stephen Harper government and the Royal Ottawa Group.

But it was doomed before Carter even arrived.

The initial plan proposed a 35- to 50-bed unit inside the secured forensic unit of the centre, which would focus on clinical, not punitive, treatment.

The centre got funding for two beds.

Carter was the first patient. She turned out to be the last.

“The whole thing was set up to fail,” Sen. Bob Runciman, an advocate for the program, told APTN.

When it was announced it was just going to be a scaled-back version, “we were all very disappointed,” Runciman said.

According to the doctor charged with running it, the government didn’t provide enough funding.

“It never got off the ground because the federal government never did it. They didn’t give the funding to get the staff. There was no support to provide the kind of treatment that was expected,” Dr. A. G. Ahmed previously told APTN.

He said the project was supposed to consist of three phases: Acute treatment, stabilization —including electroshock therapy — and finally intensive rehabilitation.

“Unfortunately we could never (do rehabilitation). We didn’t have the funding to do that,” Ahmed said.

Runciman has called for new leadership from Corrections Services of Canada, which he said can’t happen soon enough. He’s also been trying for a sit down with new Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale, but he hasn’t had any luck.

Ultimately, the blame falls on the political powers and the Harper government, he said.

Carter, meanwhile, was just recently transferred back to the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Saskatoon.

But during her time in Brockville, she was able to meet Algonquin elder Albert Dumont, who was warned about Carter.

“I saw a gentleness in her eyes right off the bat. That’s what caught my attention. It was just the way she was looking at me. She wasn’t looking at me physically, she was looking at spiritually,” said Dumont, who first saw Carter in January 2015.

By this time, Carter had already assaulted a number of the staff — including a nurse she stabbed after someone left a pen lying around.

Dumont kept visiting Carter twice a month and said he started to notice a change in her. By the spring he was finally allowed to take her outside where she walked barefoot on the grass for the first time in years.

He was also allowed to smudge with her.

“Marlene needed our way, the Indigenous way,” said Dumont.

Dumont remains convinced Carter is a product of the residential school system that saw over 100,000 Indigenous children rounded up and forced into institutions away from their families between 1880s and 1996.

“Residential schools produced Marlene Carter,” said Dumont.

It’s an established fact that the schools created an intergenerational trauma that exists to this day with the suicide crisis currently afflicting Attawapiskat in northern Ontario.

It’s also played a large part in the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in Canada’s prison system, according to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Carter never attended a residential school but her deceased mother attended St. Anthony’s on Onion Lake, and so did many of her family members, including Annabelle Knight’s mother. It’s not believed her father attended the schools, who is also deceased.

It’s also documented that many of her people were starved to death as Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, restricted food rations to Indigenous people on reserves in the Prairies to build the railway.

Those who survived were put in schools where unthinkable violence occurred.

“Drop a pebble in the water and it’s a ripple effect … it wasn’t just those that attended (residential schools) who endured the harms, but generations to come,” said an elder quoted in Carter’s 2013 Gladue report.

Near the end of 2015, Carter was being kept in a secure room with beige “institutional walls” that had just a bed, sink and toilet. There was also a window where she could see people outside.

She remained there almost until she left. Staff wanted nothing to do with her, Dumont said.

For the assault charges, Carter was found not criminally responsible. That placed her in part under the authority of the Ontario Review Board, which organized her return to Saskatoon earlier this month.

The experiment in Brockville had failed and doctors decided she needed to be closer to her family, who are trying to play a larger role in Carter’s life.

Released or doomed to die in custody

Carter’s sentence ends at the end of the summer and, barring any further charges, she’s expected to transferred to a hospital in North Battleford under the direction of the Ontario and Saskatchewan review boards that handle mentally ill patients.

But from there it’s not known what will happen.

Onion Lake has expressed interest in trying to bring Carter back to the community, but it lacks the necessary supports. APTN wasn’t able to interview the Onion Lake’s justice coordinator.

Onion Lake can apply for specialized funding under section 81 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act; according to the Elizabeth Fry Societies’ Kim Pate, the public safety minister has the authority to grant individualized community supports for Carter.

“It would be cheaper and better for her. Ultimately, she’s either going to come back into the community or, it’s horrendous to even consider it, die in custody,” said Pate.

Doesn’t Carter deserve specialized funding after all she’s been through?

“Absolutely,” said Pate. “Absolutely.”

I cried reading Marlene’s story. No one, should ever have been made to feel the way she did growing up. She was treated like garbage before she was even born, she already didn’t have a hope…. The government should help her and then some, for never having helped her before. Poor lady ☹️

#JustinTrudeau what are you doing to help this woman. Obviously suffers from severe trauma and mental health issues. Behavioral issues stemming from the previous suggestions. This is our country and this is how people are treated. Dignity stripped away, and no consequences for anyone but her.

Omg, this is so sad, my heart goes out to Marlene, she did not deserve any of this, she was just born. I pray tp great creator, that she can be saved, and healed. Iam crying as I read, govrrnment failed her, like it failed all of us indigenous ppl.

Prays. I wish to meet this woman!

My name is Melanie Pete iam her firat cousin i met her in an insitiin she looked good today i follow her now through these papers. I feel for her she was always so gentle and kind. I guess she to be owed appoligies but the goverement system really failed us all im so sorry for the trauma she went through i wish her well n stability and comfort. Maybe when shes allowed out to bring to dundamces our highest lodge of all

I love ypu marlene im glad your still with us

I am her brother .lived fifty yards from her .hearing her screams .from being hit abused.wishing I could have done some thing to help her .but all I could do was feel her pain .n cried.as I was just a kid my self .she needs spiritual healing. That I no .it always made her feel better. She led a abuse life that I no.and now reading about some of the abuse that I didn’t no about even saddens me more. Maybe these people need to say they are sorry to her personally.maybe she can forgive n help her heart heal.