Video: Rob Smith, APTN Investigates, reporting.

Jorge Barrera

APTN National News

“It could have been the Spirit himself.”

– James Pitawanakwat

He remembers it was sometime after 8:30 a.m. at the Burger King in New Westminster, British Columbia, when the stranger gave him the newspaper with a front page photograph of a masked warrior holding a stop sign girded with feathers.

James “OJ” Pitawanakwat hadn’t slept that night. He was with the hangover crowd having a fast-food breakfast. His long hair a disheveled tangle like the life he was living.

It was 1995 and the blockade trail was all dry grass in high summer. The rumble of the Canadian military machine and the report of Mohawk AK’s from the battle in the pines at Kanesatake five years earlier still echoed like distant thunder across the country.

Lighting could strike anywhere.

Pitawanakwat sat at the Burger King with last night’s liquor still on his breath with no thought beyond the greasy hash brown patty he was about to eat; no notion he would soon be thrust into the most violent confrontation in modern history between First Nations and the state.

A confrontation that would nearly kill him and lead to a life of exile.

And then the stranger appeared.

“And an Indian man come walking by looking at me, I had my long hair, probably all scraggly from the night before, and he looked at me, ‘Hey you want a newspaper.” I said, ‘sure,’ and he plopped it in front of me,” said Pitawanakwat. “He was just walking by and he handed it to me and he kept on going. It could have been the Spirit himself.”

He remembers it was the Vancouver Province newspaper and the photo was of a warrior at a blockade in Douglas Lake.

“I looked at that and I looked at what I was doing to myself and I came to the realization that I have stop what I am doing here and look at what is going on in the province,” he said. “At that moment things started happening. The dominos were falling into place that would lead me up to Douglas Lake where I had seen the man holding that stop sign.”

The trail would continue beyond, to Gustafsen Lake, and a battle over Sundance grounds in the province’s interior that would see Pitawanakwat blown up by an IED and throw him into a pitched gun battle against RCMP tactical teams firing from armoured personnel carriers driven by Canadian Forces personnel.

77,000 rounds of gunfire would rip through the underbrush during the summer conflict, eclipsing the number of bullets fired during the Kanesatake crisis.

But that was 20 years ago.

A Life in Exile

Sitting in a cold trailer on the Saginaw Chippewa Indian reservation in Michigan, Pitawanakwat sands a piece of fossilized coral called Petoskey stone he retrieved from an area near a city by the same name.

This type of ancient stone, spawned by the force of glaciers, is named after a 19th Century Odawa chief who grew wealthy from trading and settled about 200 kilometres north. He wants to mold the stone into the figure of a beaver and a clam.

“This is the leftover of the coral reef that was deposited in the Petoskey area where my ancestors are from,” he said.

The Saginaw Chippewa Indian reservation, an Anishinaabe community, is as close to home as Pitawanakwat can get. There are strong links between families here and in his home reserve of Wikwemikong First Nation on Manitoulin Island on the other side of the Canada-U.S. border that cuts through Lake Huron.

Pitawanakwat has lived here since 2004.

For nearly two decades Pitawanakwat has lived across the U.S. in places like, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Lincoln City, Oregon, where in June 2000, he was chased on his bicycle after going out for pizza, then tackled in a bramble of thorn bushes by U.S. Marshals executing an arrest warrant.

Canadian authorities had been hunting for him since he slipped across the border before finishing the day parole portion of his sentence from his 1997 conviction on charges of mischief and possession of a weapon for a purpose dangerous to the public peace in relation to the 1995 Gustafsen Lake standoff.

But the extradition request failed after a U.S. Federal Court judge in the District of Oregon ruled in November 2000 that Pitawanakwat’s actions during the standoff were “of a political character” and qualified for an exemption under the extradition treaty between Canada and the U.S.

He was granted political asylum and began a life in exile.

The Newspaper Clipping

My father tried blaming my other uncle for shooting him and her …”

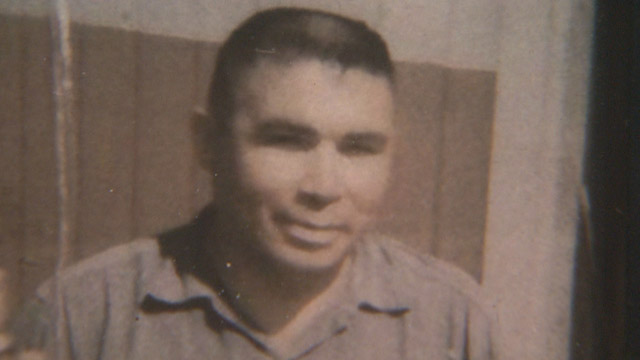

Pitawanakwat was born on July 31, 1971, the youngest of 11 children.

On October 30 of that year, his father Francis Eli Pitawanakwat, after a dance at the community hall in Wikwemikong, took his wife Mary Grace to the gravel pits and shot her dead with a bolt-action rifle. Francis Eli then turned the gun on himself in a failed suicide attempt. An uncle found Pitawanakwat’s mother’s body and the wounded Francis Eli.

“My father tried blaming my other uncle for shooting him and her,” said Pitawanakwat. “After the second trial he pled-out for eight years manslaughter.”

Pitawanakwat was raised by relatives with a different last name in Toronto and didn’t know this history until one day, when he was about 12-years-old, he was leafing through an encyclopedia at home when a newspaper clipping fluttered to the floor.

“I reached over and picked it up and seen my family name on it, my last name and I read it and I started to ask questions and they said, ‘Yeah, we went to the trial and we heard what he did to your mother,” said Pitawanakwat. “I was raised not knowing, which was fine with me, I grew up happy.”

Things began to darken for him around that same time period when he said he was molested by a Catholic priest. As he grew into his late teens he hooked up with the boyfriend of one of his sisters and entered the gang life. At first they used knives for the corner store stick-ups, then, with proceeds from the crimes, they bought pistols. They would steal cars for their getaways after hitting spots in places like Scarborough, York and Mississauga.

“I was part of the crime wave in Toronto,” he said. “We started getting a little careless and started to get closer and closer to home.”

Toronto police detectives from 14 Division, using security footage, identified him as a suspect. They picked him up and took him home where detectives showed the video to his foster parents who provided the positive identification.

He was 19-years-old and sentenced to two years. He spent stints in a Guelph, Ontario, provincial jail before he was transferred to Collins Bay penitentiary and then to Millbrook where he said a mix up with his sentence led to a complaint filed with the ombudsman which led to his release.

He ended up in Hamilton, Ontario, to be with a woman from his home community he developed a relationship with over letters and telephone calls while behind bars.

After a miscarriage—which Pitawanakwat said was caused by Hamilton police brutality while responding to a noise complaint at his apartment—the couple had a baby girl.

His father died on June 25, 1994, and was buried at the Wikwemikonsing cemetery in Kaboni on Manitoulin Island.

Pitawanakwat never met his father, he denied a request to see him when he was 16, but he did manage to speak to Francis Eli on the telephone before he died.

“I did thank him for bringing me into this world before he departed,” said Pitawanakwat.

Francis Eli and Mary Grace’s remaining 10 children, plus a daughter born to Francis Eli after the murder, gathered together for the first time at their father’s funeral. There are photographs of the day. One photograph is of the six sisters, the other of the five brothers.

“We were never together at once and most of the family was there,” said Pitawanakwat. “It was a life changing moment…to be unified even in death.”

Pitawanakwat returned to Hamilton and then he, his girlfriend, along with their new daughter, and a friend hopped the Greyhound for the West Coast.

Vision in the Clouds

Things were falling into place, the eagle bones were showing up, feathers were showing up.”

He saw the vision of the explosion after he was cut down from the tree during the Sundance.

The Gustafsen Lake standoff centred on land leased by the province to a rancher near 100 Mile House, B.C., that was used for Sundance ceremonies.

The land, which was never surrendered, was reclaimed by the Ts’Peten Defenders in 1995 who refused to leave despite attempts by the rancher to evict them.

The RCMP intervened, and, with support from the Canadian Forces, faced down the Ts’Peten Defenders, who numbered between 30 to 40 people.

Things escalated in mid-August when Defenders spokesperson William “Wolverine” Jones Ignace said if the RCMP moved into the camp it would be “clearly war…We’re not going to go peaceful. Body bags or do a hell of a long stretch…Nobody is going to tell you to put your weapons down,” according to the court record.

The RCMP and the Canadian Forces, working through Operation Wallaby, set up a base called Camp Zulu which included armoured personnel carriers, helicopters, a field hospital, communications centre, military assault weapons and a tactical unit of about 400 heavily armed militarized police.

After several incidents, which saw tens of thousands of rounds exchanged between both sides, the Defenders’ camp surrendered by Sept. 17, 1995.

There were 18 people, 13 men and five women, at the camp by the standoff’s end. All 18 were convicted by a jury following a 10-month trial.

During the standoff Pitawanakwat smuggled assault weapons purchased in the U.S. across the border and into B.C. through bush trails by foot. A group would move across the border at night to pick up the weaponry, slinging the rifles over their shoulders for the trudge back north to the camp.

It wasn’t all war, however. There was a strong spiritual aspect to the camp at the centre of the standoff.

Pitawanakwat still remembers his last Sundance and gathering the items for the spiritual ceremony that would suddenly seem to materialize.

“Things were falling into place, the eagle bones were showing up, feathers were showing up,” he said. “People were walking and they would say here is this eagle fan right here, here are these feathers for your crown, here, let’s pick up these bushes of cedar, let’s grab the red willow for thunder sticks, lets grab the tree for the dance.”

He remembers carving the Sundance pegs, which would pierce his back, from Cherrywood branches and molding the pitch into the eagle bone for the whistle. He remembers the feel of the tension from the leather rope attached to the pegs and being lifted up into the air.

“We start early in the morning when the sun comes up and you are dancing and praying when you feel the people in there and they are all dancing with you in unison and the harmony of eagle whistles and drums and you see your feet dancing,” said Pitawanakwat. “On the third day of the Sundance a few of my brothers and I were pierced from our back and were pulled up the tree and I was pulled up the tree and I was hanging from my back and we were dancing and it felt like I was up there for hours. They staked me to the ground and I was up there praying and that is when I felt people pulling me away from the tree…and that is what scared me…knowing there is something there that you can’t see.”

He shouted to be cut down. A few moments later as he felt the blood still dripping down his back, he saw the clouds.

“I seen a cloud in that state I was in, it unfolded before me at a faster rate, and I was like, ‘It’s an explosion.’ I told the elders, this is what I seen, I seen an explosion.”

To this day, he believes the vision foreshadowed what would happen to him on Sept. 11, 1995.

The IED

I was standing there, almost angry at where I was, but that was my first moment when I realized I had post-traumatic stress.”

He was driving in the pickup truck, an AK-47 and a hunting rifle inside, and Suniva Bronson, a non-First Nation activist from Alberta, in the passenger’s seat, on a water run when he hit an IED planted by the RCMP on the logging road. A YouTube video from a police eye-in-the-sky camera captured the moment of impact, the plume of smoke.

Pitawanakwat’s dog Idaho was in the back and the video shows it scrambling from the truck only to be shot by an RCMP sniper.

“It was blackness all around,” he said.

Pitawanakwat and Bronson managed to escape through the haze of smoke. Pitawanakwat headed for the lake, cut his boots off midway through the water while bullets skipped around him. The other warriors were already on the other shore and once he reached them he was handed a weapon and the gunfight exploded.

He said he still suffers bouts of PTSD from the IED strike. One of the strongest attacks hit him while he was in a holding cell in Kamloops, B.C. There was a radio on the wall playing the local commercial station. One morning, as he was emerging from sleep, one of the radio commercials played the sound of a helicopter.

“I jumped up and leapt out of bed and I was standing in the middle of that cell and a full rush of adrenaline through me,” he said. “I was standing there, almost angry at where I was, but that was my first moment when I realized I had post-traumatic stress.”

Then, later, it could be the backfire of a car, fireworks and even movie detonations that would trigger the emotions, causing his hands to shake and his mind to relive the gun battles, the explosion.

“It will always be there,” he said.

But it has faded slowly over time.

Pitawanakwat said he is selective about who he tells his story to now. He said the story of his experience in Gustafsen Lake is what got him expelled from Baraga, Michigan, after he recounted it at a bar that was also the local watering hole for off-duty police officers. One word led to another about “Indians” and he ended up in a brawl. He was thrown into the local jail and then told to get out of town on the next bus.

He planned to go to Lansing, Michigan, but chance encounters on the trip diverted his path and found him one snowy March day in 2004 at the Seven Generations cultural centre in Saginaw. He stayed for a sweat and never left.

That first night, he spent it in the sweat lodge. The next morning, he walked into the cultural centre where breakfast was being made and told his story. He said he was then given work by the cultural centre and one of his first tasks was gathering wood for the fire to make maple syrup.

There were the expected initiations, fights with the local young men testing his mettle during the pow wow and outside the bars. Eventually, he was accepted as a member of the community. He was married by the tribal chief under the pipe to Christina Keshick.

Pitawanakwat is now invited to dance with the war veterans at pow wows because of his Gustafsen Lake experience.

A longing for home

Chip Neyom became good friends with Pitawanakwat after they randomly bumped into each other 10 years ago.

“OJ is a warrior for sure. The type of guy who stands up for what he believes in,” said Neyom. “Most certainly, from his story, it’s the right thing to do, to stand up, stand your ground…sometimes we have to stand up and take arms, I guess.”

Pitawanakwat’s younger sister Melissa Manitowabi also lives on the reservation and she moved here with her husband from Canada to be closer to her brother.

“We decided to stay because I saw how much he needed family,” said Manitowabi. “Everyone is back home and some can’t come over here either and he can’t go over there.”

Manitowabi said Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould should pardon Pitawanakwat, who still has an active warrant out for his arrest in Canada, and let him come home.

“He was just standing up for what he believes in and helping the people out there,” she said. “He did a fair amount of his time. He was a free man here and he should be considered that over there too…It’s time for him to come home to be with his family.”

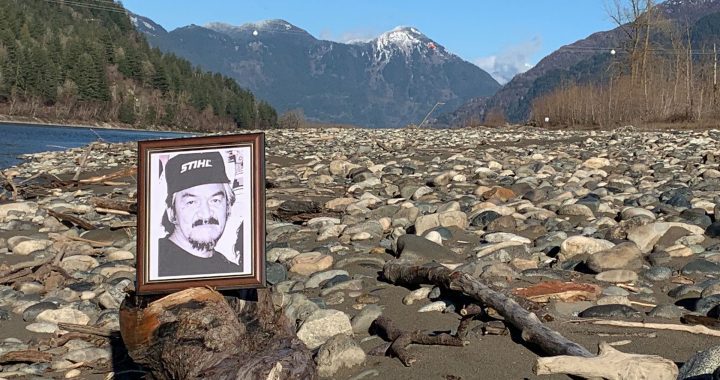

Pitawanakwat wants the right of return.

“I have been living in exile, being here, away from my family, away from my traditional territories. Being away from where I grew up is a prison sentence itself. In essence, I have been sentenced for 20 years because of this sovereignty argument,” he said. “Since I have been here I have lost a brother and a sister, people wonder why I am crying at night, when I sit here crying…I do want to return to Canada, I do want to return to the forefront.”

@JorgeBarrera